Montreal Canadiens; a Religion

par McKinley, Michael

The Université de Montréal announced in January 2009 it would offer a 16-week graduate course to future clerics called "The Religion of the Montreal Canadiens," and instead of poking fun at the ivory tower of academia, the media took the question quite seriously. Two months later, when word came out that the cash-strapped American owner of the Canadiens had put the team up for sale, the news was met with even more serious soul searching, if not a widespread spiritual crisis. The speculation was that Quebec-based saviours such as Cirque du Soleil's Guy Laliberté and René Angelil would come to the rescue of the faith. In a short time, these two events suggested that the Canadiens were much more than a hockey team, but rather, an essential component of Quebec identity in the way the Catholic Church used to be. The Canadiens' very existence provides a meaning of life for millions - for the game, its heroes and their fans do indeed make up a sort of "secular religion".

Article disponible en français : Canadiens de Montréal : une religion

« La Sainte-Flanelle »

For a century now, the Montreal Canadiens have developed and sustained an identity, which has elevated them from simple hockey team to powerful cultural icon that invites comparison to, if not recognition as, a sort of popular religion. Their 24 Stanley Cup championship banners, commemorating the team's 24 acquisitions of hockey's Holy Grail, hang from the rafters of their temple, the Montreal Forum, along with the jerseys of their messiahs, a jersey known as La Sainte-Flanelle.

Generations have learned the true meaning of passion through the team's exploits on the ice. It is a journey that has been chronicled over the decades by various faithful scribes who today include several newspapers, four daily French language TV shows that air coverage of the Canadiens, even during the dog days of summer, and on numerous radio stations in both official languages.

The Canadiens' history has transcended world wars, economic depressions, a cultural-revolution, and globalisation-for the Canadiens themselves have indeed become a global brand. In 2009, they opened a gift shop at their practice facility, so that the faithful who show up to watch the team drill can now buy icons-team-related paraphernalia such as paintings, photographs, cards, jerseys and figurines of the players. And just like the Vatican, the Canadiens have a charitable arm. While it's not a soup kitchen, it recently used its financial muscle to build an ice rink in a tough Montreal neighbourhood for the team's centennial anniversary.

During the centennial celebrations that accompanied theCanadiens' hosting of the 2009 All-Star Game, the Université de Montréal even hosted an international colloquium on the subject of the Canadiens as a religion. The academy concluded that they were close, but in the absence of a supernatural dimension, the Habs [Habitants-a nickname given to the Canadiens] were not a true faith.

Nevertheless, the Canadiens exhibit too many of the trappings of a religious faith to be easily dismissed-especially when they remain a beacon of divine constancy and benevolence for millions (when they're winning). At the heart of all religions is the belief in a superior transformative power, a divine source or pantheon of divinities with whom the believer has a personal relationship through prayers and religious experiences-some of which might be called miracles. Those who believe in the Canadiens believe they are indeed superhuman miracle-makers. Each year that the Stanley Cup does not return to its rightful place in the team's temple in Montreal produces an off-season of bitter flagellation and sober confession. Prayers for a wise selection of apostles (choosing team members in the amateur draft) and doubtless considerable (beer or alcohol) libations are offered to the gods of hockey, in order to obtain the "graces" and "divine favour" so that all will be well in the game.

Religions need divinities and believers and the occasional miracle to continue to exist-and the Canadiens have had all the above to such an extent that it's forgivable to think they sprang forth, in full bleu-blanc-et-rouge glory from the loins of a winter goddess. However, like the Catholic religion from which they take their religious bent, the Canadiens had the humblest of origins.

Origins

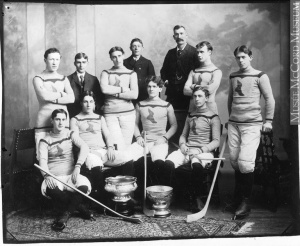

The significant event that would found the faith took place in Montreal, on March 3rd, 1875, when a transplanted, young Halifax native named James Creighton and 17 of his friends from the Victoria Rink and the Montreal Football Club played the world's first indoor hockey game. NOTE 1

James Creighton and all his friends were members of the city's English elite, and hockey would remain dominated by the Anglo-Protestant elite for years to come. The critical element was however what Creighton did for hockey-and for the future Montreal Canadiens: he created a sports environment that came to resemble a kind of religious practice.

Creighton's genius of moving the game inside-and his importation of rules and equipment from his hometown of Halifax, where the outdoor game grew to its greatest sophistication-allowed it to quickly develop into a professional sport. This controlled indoor environment allowed clubs and players to better define their own identities on the ice, and so, a star player culture was founded. As it was an indoor game, rink owners made money from renting seats to fans that wanted to watch hot and furious entertainment of the game on long cold winter nights. For fans it was also a chance to express their faith in the teams, the players, and the game.

And the game was seen from its early days as something that profoundly spoke to the Canadian spirit. "Hockey", wrote Stephen Leacock,"captures the essence of the Canadian experience in the New World. In a land so inescapably and inhospitably cold, hockey is the chance of life, and an affirmation that despite the deathly chill of winter we are alive."[1]

Combine that revelatory insight with anthropologist Johan Huizinga's observation that where we play our games is something sacred, and hockey begins to take on religious proportions:

Just as there is no formal difference between play and ritual, so the `consecrated spot' cannot formally be distinguished from the play-ground. The arena, the card-table, the magic circle, the temple, the stage, the screen, the tennis court, the court ofjustice, etc. are all in form and function playgrounds, i.e., forbidden spots, isolated, hedged round, hallowed, within which special rules obtain. Allare temporary worlds within the ordinary world, dedicated to the performance of an act apart. NOTE 2

So, when James Creighton moved hockey indoors, it became ameans for transmitting and receiving a cultural "act apart". And in 1892, when Lord Stanley, Queen Victoria's Governor-General to Canada, gave this new sport a trophy, the sanctuary had its chalice.

The popularity of the game rose rather rapidly and it would eventually come to entwine itself with the soul of Quebec and of Canada. Less than 25 years had passed between the first indoor match and the birth of the Stanley Cup (or the Dominion Challenge Trophy), as teams from across the country would challenge other top teams to compete for it. However, until the birth of the Montreal Canadiens in 1909, no team from French-speaking Canada ever had. Indeed, it was in 1900 that a French-speaking team was allowed to quest for hockey's Holy Grail and-rather appropriately-the opportunity came via religious means. Historian Michel Vigneault has argued that the arrival of both Irish and French Catholics to league hockey in Montreal was largely due to their exclusion from the leagues by the province's dominant Anglo-Protestants. The French and Irish, united by a common religion and common "enemy", learned the game together. Later, when middle class Irish Catholics were playing for the Stanley Cup-winning Montreal Shamrocks, the team welcomed French-speaking players to its ranks from 1897 through 1909.

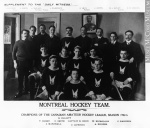

The Shamrocks were also supportive of the rise of two new French-speaking teams, the National and the Montagnard, to the top flight of amateur hockey. And so, in 1900, these two clubs were finally allowed to play in the intermediate branch of the Amateur Hockey League of Canada. French-speakers were also able to play the game at Laval University, in both Montreal and Quebec City. NOTE 3 Thereafter, the spread of the game throughout Montreal's French-speaking neighbourhoods was rapid. According to Vigneault, by 1910, 54.8% of Montreal's residents were French-speakers and of the 159 hockey clubs in the city, 55 were French-Canadian - or more than a third. So, by the first decade of the 20th century, the cultural landscape in Quebec was more than ready for the team that would become a symbol of French Canada.

It's a well-known historical fact that French-speaking Quebec was under the rule of the Catholic Church and the English bankers. And although God and money might have been powerful intangibles, the Canadiens were flesh and blood extension of a culture - a culture that could give a people a voice on the ice, whereas elsewhere it was muted or - more often not-obliged to speak the tongue of the ruling class.

« We could give it a French-Canadian name... »

Nevertheless, it was a feud in English that beg at the French-speaking team that would come to be known as Les Glorieux. It all occurred when the reigning Eastern Canada Hockey Association owners were too busy fighting over rink profits, and so a wealthy Ontario industrialist-and Irish-Catholic-Senator Michael O'Brien (who owned a team in Renfrew) combined forces with the Montreal Wanderers (also run by Irish Catholics) to create a new league. "And I think if a team of all Frenchmen was formed in Montreal it would be a real draw," Michael O'Brien's son Ambrose recalled Montreal Wanderer's official Jimmy Gardner musing. "We could give it a French-Canadian name." NOTE 4

On December 3, 1909, La Presse reported that the new team would indeed bear "le nom de Canadien" and to authenticate the choice, the newsweekly published a photo of the Canadiens' player-coach-manager, Jack Laviolette, a veteran of the pioneering French-speaking team, National, and the Montreal Shamrocks. And so, out of greed, revenge, and ambition was born one of the most successful franchises in the history of professional sports.

And were they ever magical. From 1909 to date, fifty four former Habs have been elected to Le Temple de la Renommée (whose name in French has so many more religious connotations than does in English equivalent). This is more any other team in existence. Some of hockey's greatest players have defined themselves and their game while wearing La Sainte-Flanelle, including Howie Morenz, Aurèle Joliat, Newsy Lalonde, Maurice Richard, Jacques Plante, Henri Richard, Jean Béliveau, Yvan Cournoyer, Jacques Lemaire, Guy Lafleur (Le Démon Blond) - and of course Saint Patrick Roy. A future Hall of Famer, the Habs current hope, is their goalie, Carey "Jesus" Price.

However, to see how these players and their team fit into the cosmology of the "common" fan, one need only look at a few key events connected to the Canadiens' fabled history-tales that would be deemed impossible just about anywhere else.

When the Canadiens' first great "messiah", Howie Morenz, died in March, 1937 after breaking his leg during a game against Chicago, the city of Montreal went into shock of such profundity that no cathedral or basilica was large enough to encompass the grief. There was only one place that could do so: the Montreal Forum. Morenz's body was laid at centre ice, and, with four of his team mates standing guard, more than 50,000 people filed past his casket before another 200,000 lined the streets for his funeral-the largest yet seen for an athlete in Canada.

The following year, the Montreal Maroons, the city's English team (ironically it had been created for the Anglo community by French speaker Donat Raymond in 1924) was mercifully laid to rest in the parched economic conditions of the Depression. The Maroons had won the Stanley Cup in 1935 and were home to many of the game's stars, but Montreal wasn't big enough to host two teams. Furthermore, there was no question of killing off the Canadiens, who at the time were enduring their own Cup-less spell, a drought that would last from 1931 to 1944. The Canadiens and the people they represented were united and true to the cause and any attempts to cleave the faith from the faithful would most likely result in a rebellion.

A rebellion did result from the expulsion of Maurice "Rocket" Richard (the man to whom the boys in Roch Carrier's classic story The Hockey Sweater prayed to God that they would be like) from the 1955 Stanley Cup playoffs for striking a linesman.

When NHL President Clarence Campbell suspended Richard for the rest of the 1955 season, French-speaking Montrealers rose up in protest, and the Richard Riot that ensued not only caused more than $100,000 in damage (in 1955 dollars), but, according to some academics, it also became the symbolic beginning of Quebec's Quiet Revolution. The revolution was a social upheaval that would move Quebec from a Catholic Church - English bank dominated society into the dawn of a new era that would began to take shape in the 1960s. It was a brand new society where politically-speaking French-speaking Quebeckers were finally "masters in their own house." NOTE 5

And so, with no small irony, the whole religious essence of the Canadiens came into full bloom on one Good Friday in the spring of 1984. That day, the Canadiens were hoping to advance to the Stanley Cup by winning game six against their bitter rivals, the Quebec Nordiques. The Nordiques had moved up from the defunct World Hockey Association to the NHL in 1979. Quickly they had established themselves as an upstart "faith." The ensuing rivalry with the Canadians literally divided many a Quebec household, with fathers and sons lined up against each other, the one rejecting the "faith" of the other. On Good Friday 1984, the two teams stopped playing hockey and started a brawl of such magnitude that the referees sent the teams to their dressing rooms to cooldown - only to have the brawl resume when the teams came back onto the ice. Many players were taken out of the game, and as a result, the Canadiens ended up winning the game and the series (but not the Stanley Cup that year). The brawl has become enshrined in hockey lore, but it was much more than that: the two teams were fighting for the right to be the one true faith.

A tangible tale of how French-speaking Canada sees itself

Today, the Canadiens are no longer the sole team with French Canadian hockey stars. Nevertheless, their powerful mystique and enduring mythology are such that they are still a compellingly tangible tale of how French-speaking Canada sees itself. Children are still taught to believe in team and each winter (or at September's training camp) their fans begins with a prayer that this year, the Sainte Flanelle will bring the Grail to Montreal one more time. And, as with all religions, the faith continues should the prayer not be answered. For at the powerful heart of both sport and faith lies hope.

The Canadiens illustrate Oscar Wilde's apercu that once a religion is proven to be true, it dies. NOTE 6 For hockey teams, the afterlife is always present and alive. It's either a Stanley Cup parade or the prayers for one more season. The divinely favoured team wins(and thereby is idolized and rises to the head of the pantheon) or will rise again to win the following year. Thus the religious impulse is fulfilled, sustained, or both. With the Canadiens, one just needs to believe in the future, and that les Canadiens s(er)ont là [the Canadiens will be there]. It's the perfect religion -for believers always have an attainable possibility of heaven when they find themselves in hell. It's called "the next season", and, with 24 Stanley Cups won in just a century, the odds are good for the Canadiens' faithful that heaven will come down again soon.

Michael McKinley

1. Creighton's side won, 2-1.

2. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-element in Culture, Beacon Press, 1955, p 10.

3. Hockey had developed extensively in English-speaking universities from the first indoor game until the turn of the 20th century and with the establishment of professional hockey.

4. Quoted in O'Brien. Scott & Astrid Young. Ryerson Press, Toronto, 1967.

5. David Defelice of Queen's University.

6."Religions die when they are proved to be true. Science is the record of dead religions." - Oscar Wilde, « Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young ».

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Chandail de hockey 19

Chandail de hockey 19

30-1940 -

Décès de Maurice « le

Décès de Maurice « le

Rocket », Rich... -

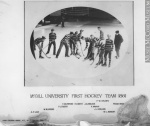

Équipe de hockey de M

Équipe de hockey de M

ontréal, champi... -

Équipement de hockey

Équipement de hockey

des Canadiens d...

-

Gordie Howe et ses ju

Gordie Howe et ses ju

meaux -

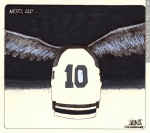

Guy Lafleur, no 10, é

Guy Lafleur, no 10, é

quipe du Canadi... -

Intérieur de la patin

Intérieur de la patin

oire Victoria, ... -

Le chandail de hockey

Le chandail de hockey

-

Merci Guy...

Merci Guy...

-

Nous interrompons ce

Nous interrompons ce

reportage sur l... -

Partie de hockey, pat

Partie de hockey, pat

inoire du Palai... -

Serge Diable, joueur

Serge Diable, joueur

de hockey

Vidéos

Hyperliens

- Montreal Canadiens: official website

- Montreal Canadiens: Wikipedia

- MONTREAL UNIVERSITY COURSE EXPLORES 'RELIGION' THAT IS HABS

- CBC Archives: Hockey

- Backcheck: A Hockey Retrospective (Library and Archives Canada)