Fort William, Crossroad of a Fur Trading Empire

par Marchildon, Daniel

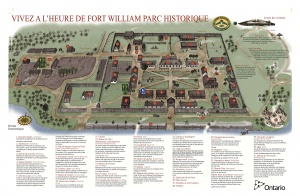

Fort William, the operations base of the North West Company from 1803 to 1821, marks a milestone in the history of Canada. Starting in 1971, the fort was faithfully reconstructed as a historical site some 15 km from its original location at the mouth of the Kaministiquia River, on the north shore of Lake Superior. Fort William is a significant location in many respects. During the 18th and 19th centuries, it played a crucial role in the fur trade west of the Great Lakes, a major industry at that time, by serving as a meeting place linking the eastern and western parts of the continent. Today, it is still a meeting place, but now it connects the tens of thousands of visitors who flock to the site every year with the experience of the First Nations, French-Canadian, and Scottish people who were the key players in the story of this important turning point in Canadian history.

Article disponible en français : Fort William, plaque tournante de la traite des fourrures

The same fort, but in two different locations

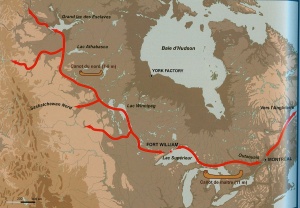

Today’s Fort William, resembling the original one constructed in 1803, is in a different location than where it first stood. The reasons for the fort’s existence stretch back to the beginning of the 18th century. At that time, in the search for furs that have become increasingly rare in the eastern part of the continent, the French venture progressively further west and north. As early as 1717, Zacharie de la Noue establishes Fort “Camanitigoyaˮ on the Kaministiquia River, close to where the present-day City of Thunder Bay is located (Note 1), with the goal of extending the fur trade towards the west. He also seeks to encourage the First Nations people to trade with the French instead of taking their furs to the Hudson’s Bay trading posts established on the shores of James Bay and Hudson’s Bay since 1670. However, the many portages impede travel on the water highway that links Fort “Camanitigoyaˮ to Lake Winnipeg and the river basin for the entire Canadian Northwest. The First Nations people show the French another route, following the Pigeon River, located to the south. This route, which has the advantage of being shorter, has only one long “grand portageˮ that stretches over 14.5 km. Thus, beginning in 1731, the Kaministiquia River fort is gradually abandoned in favour of the Grand Portage route, which becomes the preferred commercial route for several decades. With the beginning of the British regime, new fur companies are established, notably the North West Company (NWC) in 1779.

Exploration and expansion of the commercial territory

In 1778, Peter Pond, with the support of the NWC, reaches Lake Athabasca, where he discovers a territory still rich in beaver pelts. He becomes the first European to venture so far into the northwestern part of the continent (the area corresponding to the present-day northern border of the Province of Alberta). However, since this area is 5,000 km from Montreal, it is impossible to make this journey by canoe in a single summer. The obvious solution is to set up a warehouse at the halfway point where furs gathered in the North can be loaded into canoes arriving with trade goods shipped from Montreal. Grand Portage is chosen to be this transfer point. After the exchange, the canoes from the Northwest return loaded with trade goods, while those that make the return trip to Montreal carry the pelts.

In 1794, as a result of the American War of Independence, the Jay Treaty establishes a new border between the United States and the British territory. As a result, Grand Portage finds itself on American soil. In order to avoid paying duty on its merchandise, the NWC “rediscoversˮ the Kaministiquia route and, in 1803, relocates its trade operations near the site of the old French fort.

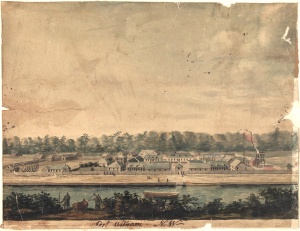

The fort revives the name Kaministiquia and, over time, comes to include some forty buildings erected on 25 acres (10 hectares). More than just a simple trading post, the fort contains storehouses, a great hall, residences for the bourgeois, that is to say, the managers of the NWC, workshops for various artisans and for repairing canoes and boats, granaries, warehouses, offices, and even a jail. These buildings are all part of the reconstructed historical site. As well as serving as a warehouse and meeting place for the canoes arriving from the Northwest and those coming from Montreal, the fort also welcomed the partners of the NWC who would hold their annual meetings there. During the summer meeting of 1807, the partners vote to rename their headquarters Fort William in honour of William McGillivray, who had replaced his deceased uncle, Simon McTavish, as the leading figure of the NWC.

An “entrepreneurial cultureˮ

By the end of the 18th century, the NWC controls over two-thirds of Canada’s fur trade. This success is due to its way of operating. Contrary to the Hudson’s Bay Company, NWC agents don’t wait for their First Nations customers to bring their pelts to them; instead they take the initiative and travel to the Native communities. As well, the associates and clerks of the NWC are “partnersˮ in the company, and thus highly motivated to maximize profits (Note 2).

Managed by William McGillivray, the company grows even more. In 1805, approximately 209,880 pounds of pelts pass through Fort William (three-quarters of them, that is 142,721 furs, are beaver pelts) (Note 3). The NWC creates its own currency, the “plue,ˮ which represents the value of one prime beaver pelt. Thus, according to the prices charged during this period, one plue is equivalent to 4.5 litres of brandy, or 8 knives, or one blanket (Note 4).

Despite the advantage the NWC gains over its English rival through its business practices, the fact remains that the Hudson’s Bay Company’s ocean port at York Factory, on Hudson’s Bay, is a tremendous asset since it allows the latter company to transport its trading wares from Europe to the heart of the American continent at half the NWC’s costs (Note 5). The NWC tries to negotiate the right to establish a post on the shores of Hudson’s Bay, but the opposition of the British government and the English trading company force it to rely on the trading network that it already possesses across the continent. The NWC also multiplies its exploratory missions in the hope of discovering a viable transportation route to the Pacific Ocean.

A profit made “on the backs of the voyageursˮ

Today, Fort William strives to be a living historical site where costumed interpreters take on the roles of historical characters: French-Canadian voyageurs, Métis, Ojibwa, and Scottish partners going about the day-to-day activities of their time. Most of the NWC voyageurs were French-Canadians. These employees made up the backbone of the NWC’s business structure; as many as 3,000 were employed in 1821 (Note 6). Historian David Morrison concludes that without a doubt the NWC turned a profit “on the back of the voyageursˮ by requiring tremendous physical efforts from them, far outweighing the wages they were paid (Note 7).

These voyageurs, often the sons of farmers accustomed to hard work, paddle from 14 to 16 hours a day and carry on average two 40-kilogram packs on their backs during the portages (Note 8). They earn between 30 and 60 British pounds a year, depending on their skills and assignments. In comparison, clerks working in the First Nations communities receive between 60 to 100 pounds a year, and an associate with two shares in the NWC can anticipate annual earnings of well over 1,000 pounds. During this period, a manual labourer in Montreal earns around 30 pounds per year (Note 9). Although most of these francophone voyageurs hope to accumulate a nest egg, they often become prisoners of a system designed to mire them in debt; the NWC has, in effect, no qualms about letting them spend their wages in advance on alcohol or luxury items (Note 10). Thus, many a voyageur gets bogged down in debt instead of becoming prosperous.

Two other groups make up the workforce: the Métis, the sons of voyageurs or clerks who live in the Northwest and become involved with First Nations women, and First Nations people, in particular the Ojibwa and the Iroquois.

Apart from the clerks and managers of the NWC, who are mostly Scottish, the company employees who rendezvous at Fort William are divided into two distinct groups. Those voyageurs who paddle the big 11-metre long canoes from Montreal are contemptuously nicknamed “the pork-eaters” because during the long voyage they eat mostly salted pork. The others, the men of the North, who live in First Nations communities, are called the winterers.

In July, when the two groups arrive at Fort William for the big annual rendezvous, they set up two separate camps outside the fort’s palisade. During these few weeks, the fort’s population explodes, going from twenty-odd people to as many as 2,000 (Note 11). The voyageurs work at tasks assigned to them by the NWC, but they also play games to test their skills and strength as well as enjoy evenings of boisterous drinking. Although when night falls the voyageurs are not allowed inside the fort, during the day they are free to roam around … and drop by the NWC’s stores where their purchases allow their employer to recoup a sizeable portion of the wages they have worked so hard to earn.

Once the furs have been pressed into packs to be transported to Montreal and the north-bound canoes have been loaded with trade goods, the two groups part in their respective directions. A mere 16 to 25 people remain to spend the winter at Fort William.

At the end of their contracts, some of the voyageurs opt to settle in the interior. They are called the “Free Canadians,” and a number of them choose to live on the other side of the river, facing Fort William, where they occasionally work for the NWC. There is also a First Nations population that camps near the fort (Note 12).

The bizarre Pemmican War

Established solely for commerce, despite the wooden palisade surrounding it, Fort William had no military purpose. Nevertheless, it was attacked during a very peculiar war, the Pemmican War, provoked by a conflict with the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1815-1816.

In 1814, near the present-day City of Winnipeg, in the Red River region, Miles Macdonell, the governor of the Scottish farming colony established there by the English Hudson’s Bay Company and Lord Selkirk, the colony’s owner, decide to prohibit the sale of pemmican (dried bison meat) outside of the HBC’s territory. The employees of the NWC depend on this staple food. A conflict becomes inevitable. In June 1816, some Métis, with the encouragement of the NWC, attack the Scottish colonists and kill 21 of them during the battle of la Grenouillère, known in English as the Seven Oaks Massacre. A few weeks later, Lord Selkirk, en route for the Red River with a company of mercenaries, arrives in front of Fort William and summons the managers of the NWC to surrender or face an attack. Selkirk arrests them and has them sent to Montreal. He then occupies the fort over the course of the winter.

Following some complex judicial wrangling, the NWC, which has a strong influence over the Canadian government at the time, obtains the release of its officers and the restitution of Fort William. Fearing a lengthy and costly legal battle, the two archrivals, the North West Company and the Hudson’s Bay Company, decide instead to negotiate a merger that occurs in 1821. Fort William becomes the property of the rival company, which maintains its headquarters in England and operates out of Hudson’s Bay, and thus the fur trade in Canada is transformed forever.

After the merger, most of the pelts that formerly passed through Fort William are sent instead to York Factory, on the shores of Hudson’s Bay. The fort ceases to be a major destination and becomes a mere relay station (Note 13). Over the next sixty years, the residents of this post will be limited to a factor, a few clerks and contract workers, the Free Canadians and the Métis families. In 1878, the Hudson’s Bay Company moves the trading post to a location within the town that is taking shape on the shores of Lake Superior and that has adopted the name Fort William. In 1970, this municipality will merge with the neighbouring City of Port Arthur to become the City of Thunder Bay. In the meantime, the HBC transfers its land around Fort William to the Canadian Pacific Railway, which uses it to build its rail terminus in 1883.

Preserving the past while building the future

The last original building of the old Fort William is torn down in 1902 (Note 14). In 1908, the Thunder Bay Historical Society erects a monument in front of the fort’s original location. Sixty years later, the Ontario government finances archeological excavations on the site of the railway terminus that is still in operation, forcing the archeologists to dig between the train tracks (Note 15).

On January 20th, 1971, Ontario Premier John Robarts announces the reconstruction of Fort William, which is scheduled to begin the following spring. The site will be built approximately 15 km upriver on the shores of the Kaministiquia. It is deemed impossible to recreate the site at its original location because its ruins are buried under the rail terminus, businesses, and homes in an industrial part of the city that no longer has the natural setting needed to evoke the atmosphere of an isolated 19th century trading post. Two years later, on July 3rd, 1973, the site welcomes its first historical and heritage enthusiasts, including Queen Elizabeth II, who officially opens it.

Reconstructed to appear as it would have at its heyday in 1815, Fort William welcomes approximately 100,000 visitors every year despite the fact that it is located a good distance from any large urban centre. During the school year, the site offers some twenty educational programs and holds over ten events for the general public, including a voyageurs’ winter carnival and a First Nations festival called Anishnawbe Keeshigun. Run by the Ontario government, Fort William Historical Park also boasts an outside amphitheatre that can accommodate up to 50,000 people, as well as conference and banquet facilities. At the end of 2012, the site opened the David Thompson Astronomical Observatory, named in honour of one of the most celebrated pillars of the Northwest Canadian fur trade. Thompson, who was a partner in the NWC, an outstanding explorer and mapmaker, as well as the author of books about his journeys, holds the distinction of being the first European to have ventured down the Columbia River from the Canadian Rocky Mountains to the Pacific Ocean in 1811. This route remains the commercial highway through the mountains until the construction of the railway.

The Fort William historical site’s motto, “Preserving the past while building the future,ˮ sums up its mission. By imparting an awareness of the distinct roles of the First Nations, the French and the British in the fur trade, including that of Native women and their mixed-blood progeny, the Métis, the site strives to illustrate the diversity of the peoples that founded Canadian society (Note 16).

Today’s Fort William remains a crossroad, but now between our present-day world and the grand era of the fur trade, when, at the beginning of the 19th century, the French-Canadian voyageurs played a crucial role in the race towards profits and the westward territorial expansion of Canada.

Daniel Marchildon

A writer from Huronia, in Ontario, where he still resides, and the

author of over twenty publications, including eleven novels for young adults

and the general public, as well as works of history.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

A group of interprete

A group of interprete

rs in the role ... -

A group of interprete

A group of interprete

rs in the role ... -

A group of interprete

A group of interprete

rs playing the ... -

An aerial view of For

An aerial view of For

t William Histo...

-

Campement d'explorate

Campement d'explorate

urs de la Cie d... -

Campement indien, for

Campement indien, for

t William, 1912 -

Culture matérielle au

Culture matérielle au

fort William: ... -

Église Saint-Patrick,

Église Saint-Patrick,

Fort William, ...

-

Expédition de la Rivi

Expédition de la Rivi

ère Rouge : le... -

Finnish farm in the F

Finnish farm in the F

ort William Dis... -

Fort William on Lake

Fort William on Lake

Superior, circa... -

Fort William vu du cô

Fort William vu du cô

té sud de la ri...

-

Fort William, 1866.

Fort William, 1866.

-

Fort William, 1873

Fort William, 1873

-

Fort William, Ont. (i

Fort William, Ont. (i

llustration pré... -

Fort William, sur les

Fort William, sur les

bords du lac S...

-

Fort William, un comp

Fort William, un comp

toir de la Comp... -

Le Cochon d'inde, le

Le Cochon d'inde, le

Castor [Guinea ... -

Map showing the trade

Map showing the trade

routes linking... -

Old Fort William and

Old Fort William and

the Hudson’s Ba...

-

Preliminary design fo

Preliminary design fo

r a coat of arm... -

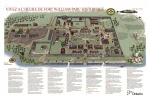

Site map of Fort Will

Site map of Fort Will

iam Historical ... -

Vue du fort William a

Vue du fort William a

̀ partir d'un c... -

William McGillivray,

William McGillivray,

circa 1805.

Catégories

Notes

1. Jean F. Morrison, Superior Rendezvous-place: Fort William in the Canadian fur trade, 2ndedition, Toronto, Natural Heritage Books, 2007, p. 14.

2. David Morrison, Profit and Ambition: The North West Company and the Fur Trade, 1779-1821, Gatineau, Society of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2009, p. 13.

3. Morrison, J.F., op. cit., p. 50.

4. Morrison, D., op. cit., p. 39.

5. Morrison, J.F., op. cit., p. 114.

6. TFO, web site, Voyageur’s World, ‘Hired under contract’ article in the section Work Life,

http://www.tfo.org/emissions/rendezvousvoyageur/en/index.html

7. Morrison, D., op. cit., p. 29.

10. Morrison, D., ibid, p. 29.

11. Susan Campbell, Fort William: living and working at the post, Fort William Archaeological project, Ontario ministry of Culture and Recreation, 1976, p. 26.

12. Arthur Black, Old Fort William, Not the definitive, authorized, shrinkproof, cling-free story…, Thunder Bay, Old Fort William Volunteer Association, 1985, p. 52.

13. Morrison, J.F., op. cit., p. 120.

14. Morrison, J.F., ibid, p. 131.

15. Morrison, J.F., ibid, p. 132.

16. Morrison, J.F., ibid, p. 137.

Bibliographie

Black, Arthur, Old Fort William, Not the definitive, authorized, shrinkproof, cling-free story…, Thunder Bay, Old Fort William Volunteer Association, 1985, 69 pages.

Campbell, Susan, Fort William: living and working at the post, Fort William Archaeological project, Ontario ministry of Culture and Recreation, 1976, 123 pages.

Morrison, David, Profit and Ambition: The North West Company and the Fur Trade, 1779-1821, Gatineau, Society of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2009, 64 pages.

Morrison, Jean F., Superior Rendezvous-place: Fort William in the Canadian fur trade, 2ndedition, Toronto, Natural Heritage Books, 2007, 164 pages.

Morning in the North West, docudrama in two one-hour episodes, directed by Jean Bourbonnais, Les Productions Rivard, 2004-2005.

![Le Cochon d'inde, le Castor [Guinea pig, Beaver], 1745-1811?](/media/thumbs/7940/245x300-7940_fort_william_14E.jpg)