Canadian National Vimy Memorial

par Pépin, Carl

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is the largest monument to Canadian soldiers who gave their lives in the First World War. Located on Vimy Ridge in northern France, the memorial is the centrepiece of the park marking the site of the battle of the same name, which took place from April 9th to 12th, 1917. The monument also commemorates the sacrifice of Canadian soldiers whose graves are unknown. The history and symbolic importance of the Vimy Memorial andthe numerous commemorative ceremonies held there lend international importanceto this place of remembrance.

Article disponible en français : Monument commémoratif du Canada à Vimy

Description of the Memorial

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial is located on the ridge of the same name, eight kilometres [5 miles] north of Arras in the French Department [regional territorial subdivision] of Pas-de-Calais, near the villages of Vimy and Neuville-Saint-Vaast. Running seven kilometres from north to south, Vimy Ridge slopes gradually to the west, although more steeply on its eastern flank. The 101-hectare [250-acre] commemorative park offers unobstructed views of the Pas-de-Calais region for 35 kilometres every direction. The remains of trenches and shell holes testify to the fierceness of the fighting during the 1917 battle.

The memorial was built under the supervision of Toronto architect Walter Seymour Allward. Construction took 11 years and cost $1.5 million. The monument was unveiled on July 26th, 1936, by King Edward VIII of England in the presence of the President of the French Republic, Albert Lebrun and 50,000 Canadian and French veterans of the Great War and their families. After extensive restoration undertaken in 2004, the memorial was rededicated by Queen Elizabeth II in April of 2007 during a ceremony marking the 90th anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Veteran Affairs Canada is responsible for the upkeep of the memorial and general administration of the commemorative park.

Architect Allward had the memorial built on Hill 145, the highest point on Vimy Ridge. The monument comprises various symbolic elements, including human figures, military objects, and inscriptions evoking the values for which Canadian soldiers sacrificed their lives. From a distance, visitors are immediately struck by the two massive limestone columns that rise 30 metres into the air. The 6,000-ton columns sit on a rectangular cement base weighing some 11,000 tons. The limestone for the columns was brought from an abandoned Roman quarry on the Adriatic Sea, in present-day Croatia. The columns represent Canada and France and are adorned at the top with several statues representing, among other things, Truth and Knowledge.

One figure that stands apart from the ensemble is that of a woman. Facing the Douai Plain to the east, Mother Canada (also known as Canada Bereft) turns her gaze downward, her sad face symbolizing a young Canadian nation mourning its fallen sons. On the western side of the memorial, the statues of a man and woman represent the parents of the fallen soldiers. As for the seven-metre-high base anchoring the structure, it symbolizes the defences erected against the enemy. On each side of the base are inscribed the names of the 11,285 Canadian soldiers killed in France whose final resting place is unknown.

Symbol of the Ultimate Sacrifice

The Vimy Memorial not only commemorates Canada's great World War I victory at Vimy, but also pays tribute to all those risked or gave their lives to serve their country during the four years of fighting. Consequently, the memorial has considerable cultural and heritage significance in Canada. Its imposing presence on the ridge where so many soldiers died recalls a widely held Canadian view that the Canadian nation was forged in blood and steel on the battlefields of Vimy in 1917.

The erection of the memorial between the two world wars was the expression of a new Canadian nationalism that drew on the experiences on the battlefields of Europe to define its values. From another point of view, the significance of the Vimy Memorial extends beyond the ridge to symbolise Canadian sacrifices throughout all the wars of its history. The money invested by the Canadian government to restore the memorial in the early 2000s also signalled Canada's determination not to forget the human cost of the war of 1914-1918, or of the other conflicts that followed.

Another indication of the Vimy Memorial's heritage value is the fact that it is one of only two historic sites outside of Canada recognized by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. Again, the monument does much more than commemorate the battle of 1917; it represents the sacrifice of the 60,000 Canadian soldiers who lost their lives in World War I, over 11,000 of whom lay in unmarked graves. Some 7,000 soldiers are buried in 30 military cemeteries within a 20-kilometreradius of the commemorative park.

The Battle of Vimy Ridge

A natural observation point of vital strategic importance, Vimy Ridge fell to the Germans at the beginning of the war in October 1914 during the Race to the Sea, a series of battles and skirmishes that saw the opposing armies try to outflank each other in a bid to regain the upper hand on a constantly moving battlefront. The French army tried unsuccessfully on several occasions to oust the Germans, losing more than 100,000 men overall in their attempts to recapture the ridge and the surrounding terrain. The 17th British Expeditionary Corps stepped in to relieve the French in the sector in February of 1916.

In October of 1916, the four infantry divisions of the Canadian Corps moved in to relieve the British. The Battle of Vimy Ridge in April of 1917 was the first (and only) attack conducted simultaneously by all the divisions of the Canadian Corps during the war. After five months of preparation, the attack was launched early on the morning of April 9, 1917. In the days that followed, the Canadians suffered over 10,000 casualties, including some 3,600 deaths, making Vimy the bloodiest Canadian engagement of World War I.

The Vimy Memorial

It was in 1922, after a series of intergovernmental discussions, that France ceded part of the 1917 battlefield in perpetuity to Canada. Construction of the memorial began in 1925, and lasted 11 years. The lion's share of the work was performed by British and French workers, mostly veterans, placed under the supervision of Allward, who reported to the Imperial War Graves Commission.

Allward himself spent more than two years scouring Europe for the right material for the monument. He finally found fine quality limestone in an abandoned Romanquarry in present-day Croatia. Logistical challenges delayed delivery of the stone to the site. As a result, work on the actual monument did not get underway until 1927 and as late as 1931 for some of the statues.

While they waited for the limestone to be delivered, the workers kept busy restoring the site. First, they had to secure the area by removing mines, human remains, and all other vestiges of the Great War. To lend authenticity to the site, the walls of the old trenches were cemented so that visitors could walk along the mand imagine the layout of the front lines.

When the Vimy Memorial was finally unveiled in 1936, there were over 8,000 Canadians inattendance. The site soon became a popular destination for battlefield pilgrims. However, serious concerns about its safety arose during the German occupation during the Second World War, when rumours began to swirl in Canada about its possible destruction. To put an end to the rumours, the German propaganda minister went so far as to release photos showing Adolf Hitler visiting the memorial in June of 1940.

By the turn of the century, several decades of exposure to the elements and water damage had taken its toll on the monument. In May of 2001, the Canadian government announced a major battlefields memorial restoration project. Over $10 million was invested and the commemorative park was temporarily closed to visitors in 2005 for restoration work. It was reopened to the public in April of 2007 in time for the 90th anniversary commemoration of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Today, the memorial continues to attract thousands of visitors and numerous school groups every year. There are also guided tours led by Canadian students.

A Pilgrimage Site

The site is readily accessible by car, taxi, and tour bus, but is not currently served by public transit. For many years, numerous Canadian visitors used the shuttle service provided by Georges Devloo, a resident of Vimy, who would visit the train stations in Arras and the surrounding villages every day in his car in search of "errant" Canadians. For 13 years until his death in 2009, the "Grandfather of Vimy" - as he was nicknamed by the Canadian guides-brought hundreds of Canadians to the monument free of charge. His contribution has been recognised by the Canadian government.

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial has been the subject of numerous media reports and documentaries and is an international model of heritage presentation for the war of 1914-1918. It is a moving testimony to the horrors experienced by Canadian solders in battle.

Carl Pépin, Ph.D.

Historian

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Beatty, David Pierce, The Vimy Pilgrimage, July 1936: From the Diary of Florence Murdock, Amherst, Nova Scotia, Acadian Printing, 1987.

Brown, Charles Hutton, Books of Remembrance, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1983.

Gibson, T. A. Edwin, Courage Remembered: The Story Behind the Construction and Maintenance of the Commonwealth's Military Cemeteries and Memorials of the Wars of 1914-1918 and 1939-1945, Toronto, McClelland & Stewart, 1989.

Hale, Katherine, Canada's Peace Tower and Memorial Chamber, Designed by John A. Pearson: A Record and an Interpretation, Toronto, Mundy-Goodfellow Printing, Co., 1935.

Mills, Stephen, Task of Gratitude: Canadian Battlefields of the Great War, Calgary, Vimy Ventures, 1997.

Nicholson, G. W. L., "We Will Remember...", Overseas Memorials to Canada's War Dead, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1973.

Shipley, Robert, To Mark Our Place: A History of Canadian War Memorials, Toronto, NC Press, Ltd., 1987.

Veterans Affairs, The National War Memorial/Le Mémorial national de guerre, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1982.

----------, Memorials to Canada's War Dead/Mémoriaux aux Canadiens morts à la guerre, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1985.

----------, The Vimy Memorial, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1987.

----------, Le Monument commémoratif à Vimy/The Canadian National Vimy Memorial, Ottawa, Veterans Affairs, 1990.

Vance, Jonathan F., Death So Noble: Memory, Meaning and the First World War, Vancouver, UBC Press, 1997.

Wood, Herbert Fairlie, and John Swettenham, Silent Witnesses/Témoins silencieux, Toronto, Hakkert, 1974.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affiche prévenant les

Affiche prévenant les

visiteurs de n... -

Bataille sur la crête

Bataille sur la crête

de Vimy, sur l... -

Concours de design vi

Concours de design vi

sant à choisir ... -

Construction de la fo

Construction de la fo

ndation du monu...

-

Unveiling of Canada's

Unveiling of Canada's

National Memor... -

Ghosts of Vimy Ridge,

Ghosts of Vimy Ridge,

1931 -

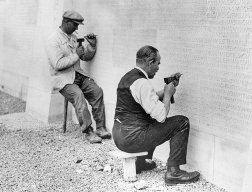

The delicate carving

The delicate carving

of names on the... -

Homme se tenant près

Homme se tenant près

d'un bloc prêt ...

-

Le monument de Vimy,

Le monument de Vimy,

quelques moment... -

Mère Canada avec vue

Mère Canada avec vue

au nord, 2007 -

Mother Canada, 2004

Mother Canada, 2004

-

Canadian National Vim

Canadian National Vim

y Memorial and ...

-

Monument de Vimy, 200

Monument de Vimy, 200

7 -

Monument de Vimy, Pas

Monument de Vimy, Pas

-de-Calais, Fra... -

Monument de Vimy, Pas

Monument de Vimy, Pas

-de-Calais, Fra... -

Noms des soldats grav

Noms des soldats grav

és dans le socl...

-

Aerial photograph of

Aerial photograph of

the official un... -

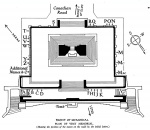

Plan du monument de V

Plan du monument de V

imy, 1930 -

Programme officiel du

Programme officiel du

pèlerinage à V... -

Soldats canadiens sur

Soldats canadiens sur

la crête de Vi...

-

Statue à demi achevée

Statue à demi achevée

, à côté de du ... -

Statue illustrant l'e

Statue illustrant l'e

sprit du sacrif... -

Tranchée sur la crête

Tranchée sur la crête

de Vimy, 2006... -

Visite d'Adolf Hitler

Visite d'Adolf Hitler

à Vimy, 1944