Montreal Botanical Garden

par Bélanger, Diane

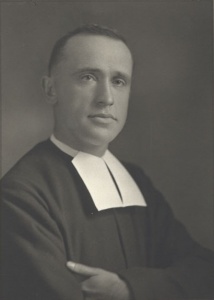

The Montreal Botanical Garden owes its existence to one man's determination. A priest known as Brother Marie-Victorin (1885-1944), the eminent French-Canadian botanist and teacher, dedicated himself to promoting the importance of scientific learning among his compatriots at a time when science was little valued in traditional French-Canadian society. The Garden is one ofhis most lasting achievements. Designed by the visionary landscape architect Henry Teuscher, the Montreal Botanical Garden is sometimes referred to as a"northern wonder." The internationally renowned facility marries natural beauty with an educational vocation, as its founder intended. It is also one of Montreal's major tourist attractions.

Article disponible en français : Jardin botanique de Montréal

A Vast Northern Garden

The 75-hectare [185-acre] Montreal Botanical Garden is located in East-end Montreal on the site of a former novitiate school belonging to the Institute of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, the religious order of Brother Marie-Victorin. The entrance is laid out like a French garden and leads to the Art Deco-style administration building constructed between 1932 and 1938. Interestingly, Architect Lucien Kéroack chose to ornament the building's facade with four terracotta bas-reliefs by the sculptor Henri Hébert. The bas-reliefs illustrate the horticultural knowledge of North America's first peoples and their use of native plants.

Another well-known feature of the Garden can be found at the main entrance, where exotic tree species like the Kobus magnolia (Magnolia kobus) and the tulip tree (Liriodendron tulipifera) thrive at the northern limit of their natural range amidst annual flower arrangements showcasing the latest developments in horticultural knowledge. Further on, ten exhibition green houses that stay open all year round pay tribute to the plants of every continent. Admiring the fruit of a tropical carambola tree on a winter morning when it is -20oC outside is part of what makes the Montreal Botanical Garden experience so unique. Every year, the displays of Quebec perennials, the superb rose garden, the thematic and water efficiency gardens and the temporary exhibitions and numerous cultural activities attract millions of visitors.

A Botanical and Cultural Heritage

The size and scale of the Garden make it an invaluable cultural asset, both interms of the diversity of its natural and cultural attractions and its mission in promoting the scientific knowledge of our botanical heritage. Created in the 1930s in the midst of the Great Depression, the Garden is a testament to Quebec's transformation into a modern society. It grew and developed in tandem with key events in the province's history, notably the Second World War and the wave of internationalisation sparked by the Universal Exhibition of 1967. Thanks to the "ideal garden" program implemented by Henry Teuscher (the landscape architect chosen by Marie-Victorin) the Montreal Botanical Garden has developed harmoniously over the years to reflect both the natural diversity of Quebec and the cultural diversity of contemporary Montreal.

An Island Garden

The dream of creating a botanical garden on Montreal Island's vast tracts of green space first emerged in the 19th century among the city's English-speaking elite. Initial plans for a garden on Mont Royal fell victim to administrative red tape. Understandably, the creation of such a garden in Quebec's harsh climate required significant investments and a healthy dose of determination. In the end, it was Marie-Victorin, a humble member of Brothers of the Christian Schools movement, who would see the dream through to reality, driven by his passion for scientific research and his determination to awaken his contemporaries to the importance of scientific learning.

Marie-Victorin, a Man of Conviction

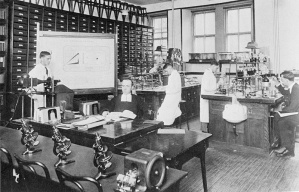

Brother Marie-Victorin was born Conrad Kirouac in 1885. He entered the Order of the Christian Brothers, a religious community devoted to primary and secondary education, when still a youngster. By age 16, he was teaching various subjectsin the Christian Brothers' schools. His early interest in sciences led him to realise that his French-speaking colleagues, with their penchant for the classics and humanities, lagged far behind in the sciences. Spurred on by a world changing rapidly before his eyes, Marie-Victorin was determined to reverse this trend and foster an interest in scientific advances and newly emerging technical knowledge among French Canadians. He stopped teaching theatre, and began to teach math.

Fragile of health, the frail young brother was often confined to the infirmary, library and garden. He became the assistant gardener at Collège de Saint-Jérôme, where he quickly realised his own ignorance and how little information was available about the plants of Quebec and about the natural sciences in general. It was during this period that his passion for botany was born. From this point on, Marie-Victorin set about exploring the province, collecting and studying plants, and most importantly, publishing his findings. By 1910, he had begun to make plans for a guide to the plants of Quebec, a project that finally came to fruition in 1935 with the publication of his classic work Flore Laurentienne, still a reference in the field today. Throughout these years, Marie-Victorin corresponded with leading natural scientists in Canada, Europe and the United States.

Through his publications and his activities with the Young Naturalists Clubs, Marie-Victorin became something of a scientific celebrity. Although self-taught, he was appointed the first Chair of Botany in 1920 at the newly established Université de Montréal. In 1923, he helped found ACFAS, the Association Canadienne-Française pour l'Avancement des Sciences [French Canadian Association for Scientific Development]. In 1929, he represented the Université de Montreal at the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in South Africa. He took advantage of the opportunity to visit botanical gardens in the major cities of Europe and Africa and came back convinced that Montreal had to have a garden of its own. So began a ten-year battle to bring his vision to life.

A Rocky Start

Marie-Victorin's plans for a garden could hardly have come at a worse time. Quebec was hit hard by the Great Depression triggered by the stock market crash of October 1929 and unemployment was rampant. Undeterred, Marie-Victorin penned newspaper articles for Le Devoir, an unwavering ally,and drew on the backing of the Association du Jardin Botanique de Montréal, founded in January of 1930. The City of Montreal agreed to support the garden project, but progress was painfully slow. First, a portion of Maisonneuve Park was set aside for the future garden in March 1931. Then, in 1932 Marie-Victorin entered into correspondence with Henry Teuscher, a German botanist living in the United States, who was recommended to him by the head of the New York Botanical Garden. With funding for the projecton hold, the two men wrote back and forth for four years, during which period Teuscher drafted his Program for an Ideal Botanical Garden. Finally, Marie-Victorin found the ally he needed in one of his former students, Camilien Houde, who had recently been re-elected as mayor of Montreal. Writing to Mayor Houde in 1935, Marie-Victorin showed his eloquence in stating his case as he evoked preparations for the 300th anniversary of the city in 1942: "You need to give a gift, a royal gift, to the City, our city. But Montreal is Ville-Marie, a woman...and you certainly can't give her a storm sewer or a police station... It's obvious what you must do! Give her a corsage for her lapel. Fill her arms to overflowing with all the roses and lilies of the field."

Henry Teuscher, the Other Father of the Garden

Henry Teuscher arrived in Montreal in 1936 after being appointed superintendent and chief horticulturalist of the future Montreal Botanical Garden. The first sod was cut on May 7th, 1936, and in the fall, Teuscher hired 2,000 unemployed men under the Quebec government's unemployment assistance program. For three years, the men worked to build the administration building and production greenhouses, put in roads and excavate the Garden's two lakes. By 1939, the main thorough fares were completed. With the outbreak of war, however, work slowed considerably. Henry Teuscher was even accused of Nazism, but his name was cleared and he kept his position. Today, the German botanist is considered the other father of the Garden and specialists agree that the quality of his plans and their consistent implementation explain the harmony and extraordinary beauty of the Garden.

The War Years

Despite the challenges, Marie-Victorin never wavered in his commitment to youth education, pursuing his pedagogical mission by creating a horticultural school and the Young Gardeners program. As director of the Institute of Botany at the Université de Montréal, Marie-Victorin spearheaded efforts to foster collaboration between the Institute and the Garden in 1943 with respect to research and public education. Sadly, Marie-Victorin died on July 15th,1944, from injuries he sustained in a car accident. Upon his death, tributes flooded in from far and wide acknowledging the immense scientific, cultural and social contributions of this central figure in the modernisation of Quebec society.

A New Generation

Everas a teacher, Marie-Victorin had groomed his successors well. Jules Brunel, his first student, stepped in to lead the Institute of Botany and Jacques Rousseau, his right-hand man, became director of the Garden. Rousseau had been Marie-Victorin's stead fast companion in the many battles he had waged for the Garden. A brilliant scientist in his own right, and the secretary of ACFAS, Rousseau contributed significantly to fostering the Garden's scientific vocation, notably through his extensive exploration and field work across theprovince. He also oversaw the construction of the exhibition greenhouses, which allowed the Garden to operate year round.

Pierre Bourque, the Creator

The Garden went into something of a decline in the 1960s. Montrealers were absorbed by other projects like the 1967 Universal Exhibition. In the end, it was Parc des Îles at Expo 67 that ended up providing fresh leadership for the Garden in the person of Pierre Bourque. Initially hired as section manager of the outdoor gardens, he took on the challenge of revitalising the Garden with his colleague Émile Jacqmain, the Garden superintendent. Bourque had his students at the Université de Montréal's School of Landscape Architecture draw up plans for new gardens, including the Flowery Brook and the Rose Garden. Numerous other initiatives also sprang from his fertile imagination.

The Garden Goes International

Pierre Bourque was especially active at the international level, notably as the organiser of the first International Floralies Fair held in North America in 1980. This horticultural exhibition introduced the general public to Japanese bonsai and Chinese penjing, and the acquisition of major oriental collections paved the way for the creation of two remarkable Asian gardens under the leadership of Bourque, who became director of the Botanical Garden in 1980.

The Japanese Garden

The design of the Japanese Garden was entrusted to renowned landscape architect Ken Nakagima, who had worked on an initial version of the project in 1967. The garden was finally completed two decades later, in 1988. Despite its contemporary design, the garden meets the fundamental criterion of all traditional Japanese gardens: harmony. Water, stone and plants are combined to create a sense of inner peace. The garden posed major challenges to the design team, notably in choosing plants equivalent to ones used in Japan, but adaptedto Montreal's climate. The choice of stone, another crucial element in Japanese garden design, also took a great deal of time and research. The architect eventually settled on a green-coloured stone from the Thetford Mines region. The stone provides a framework for the plants and a foundation for the garden's waterfall and streams, with their Koi carp, called "living flowers" by the Japanese.

The Chinese Garden

The Chinese Garden opened in 1991 and is the largest garden of its kind outside China. It is the result of a joint venture with Montreal's twin city, Shanghai. Taking inspiration from the private gardens of the Ming Dynasty (14th to 19th century), Chinese architect Le Weizhong created an asymmetrical garden that plays on the contrasts between yin and yang. Officially named Meng hu, or Dream Lake Garden, it numbers seven pavilions, including the central Friendship Hall (Qinyi tang). Feature plants in the garden include the tree peonies mentioned by Italian explorer Marco Polo in the 13th century as well as lotuses, also known as "Buddha flowers". Every fall, the spectacular "Magic of Lanterns" event brings the garden to light with the flickering silhouettes of dragons, fairies, and other mythical creatures.

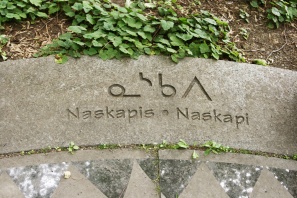

The First Nations Garden

The First Nations Garden showcases native North American plants and the special bonds between aboriginal peoples and the plant world. The garden is divided into three sections featuring plants of importance for Iroquoians, Algonquins and Inuit. In fact, a garden of "Indian" medicinal plants was included in the initial garden plans drawn up by Brother Marie-Victorin and Henry Teuscher. The First Nations Garden opened in 2001 on the occasion of the 300th anniversary ofthe Great Peace of Montreal signed in August of 1701.

Conclusion

The Montreal Botanical Garden is a constant source of wonder thanks to its collection of over 22,000 species and varieties of plants, ten exhibition greenhouses and thirty-odd theme gardens. Some of them are more low-key, like the Leslie Hancock Garden that lies hidden behind a curtain of evergreens and which is at its finest in May when the rhododendrons bloom. Others like the Chinese Garden are major attractions. The sheer size of the Botanical Garden, along with its numerous exhibitions and activities and its research team, make it one of the biggest and most beautiful botanical gardens in the world.

Diane Bélanger

Historian

BIBILOGRAPHY

Bouchard, André and Francine Hoffman Le Jardin botanique de Montréal. Esquisse d'une histoire, Montréal, Éditions Fides, 1998, 111 p.

Couture, Pierre, Marie-Victorin, Le botaniste patriote, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, 1996, 215 p.

Couture, Pierre and Camille Laverdière, Jacques Rousseau. La science des livres et des voyages, Montréal, XYZ éditeur, 2000, 175 p.

Desrochers, Jacques, Étude historique et analyse patrimoniale du Jardin botanique de Montréal, Montréal, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, Direction régionale de Montréal, July 1995, 2 v.

Hoffman, Francine, "Henry Teuscher, un homme et des jardins", Quatre-temps, La revue des amis du Jardin botanique de Montréal, vol. 23, no. 3, September 1999, p. 48-49.

Lincourt, Jean-Jacques, Jardin botanique de Montréal, Collection Les guides des jardins du Québec, Montréal, Éditions Fides, 2001, 111 p.

Teuscher, Henry, "Programme d'un jardin botanique idéal", Mémoires du Jardin botanique de Montréal, Le Jardin botanique de Montréal, No. 1, 1940, 34 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Aechméa

Aechméa

-

Couverture du Program

Couverture du Program

me d'un jardin ... -

Henry Teuscher

Henry Teuscher

-

L'étang situé au coeu

L'étang situé au coeu

r du Jardin bot...

-

Le jardin japonais so

Le jardin japonais so

us la neige -

Le jardin zen au pavi

Le jardin zen au pavi

llon japonais -

Statue du Frère Marie

Statue du Frère Marie

-Victorin à l'e...