Parc national du Mont Tremblant

par Cadieux, Louise

The wildnature of Parc National du Mont-Tremblant [Provinical Park] draws visitors to the region year-round. With mountains, 400 lakes, six rivers and stands of fir and pine trees as far as the eye can see, the 1,510-km2 [583 square-mile] park features broad scenic vistas of Laurentian landscape. From the time it was founded as a forest reserve in 1895 and when it was finally recognised as a national park in 2001, the park has been subject to several changes over the years, whether it be to its boundaries or its land use. Throughout the park's history, the use of its forests and wildlife has reflected the evolution of the cultural and economic values of the society that created it.

Article disponible en français : Parc national du Mont-Tremblant

The Oldest Park in Quebec

At the time of its creation in 1895, Parc de la Montagne Tremblante covered 60 km2 [23 square miles], most of which was occupied by the mountain itself. In founding the park, the Quebec government was following a North American trend that had led to the creation of Yellowstone National Park in the U.S. in 1872 and Banff National Park in Alberta in 1885. Despite being labelled a park, the area was in fact a special State-run forest reserve, since logging companies were allowed to operate in its forests and private hunting and fishing clubs served a small number of well-to-do sportsmen. The park, which was originally linked to the forestry industry that developed at the same time the region was settled and then in response to the rise in tourism and outdoor activities, has relied on the region's abundant natural resources throughout its history. Over the years, the area's forests, animal species and scenic landscapes have all been put to use for economic, scientific, tourist and environmental purposes. A number of public and private initiatives have been aimed at promoting and preserving the area's natural heritage for years to come.

The Growth of the Region

Development of the region surrounding Mont Tremblant began in the mid-19th century. To the west of the park, settlers founded the towns of La Conception (1875), Labelle (1878), Saint-Jovite (1879), L'Annonciation (1880) and Saint-Faustin (1881). To the east, Saint-Côme (1862), Saint-Michel-des-Saints (1863) and Saint-Donat (1874) were founded during another movement to settle the region. While logging companies of the day were often owned by English-speaking proprietors, the lumberjacks and draveurs [log drivers] they employed were French-Canadian farmers from neighbouring towns. Since the soil in the region was poor and the growing season very short, settlers split their time between their fields and the logging camps in order to make ends meet.

At the same time, the region's natural beauty led to the creation of a tourist industry centred around its exceptional natural setting. Following the advent of rail service to the Mont Tremblant area in 1893, a resort industry developed around the region's lakes. A number of VIPs, mainly English Canadians and Americans, took part in hunting and fishing trips organised by private clubs and outfitters established at former logging camps. The presence of American and English-Canadian logging companies and clubs explains why many of the park's lakes have decidedly English-sounding names.

Despite changes to quotas and resource-management aimed at protecting waterways and forests, the park's forests and wildlife continued to be exploited for decades. Logging companies controlled access tothe park until the late 1950s, limiting access to visitors for fear of forest fires.

The Exploitation of Natural Resources

Before the arrival of Europeans, Amerindians would visit the Mont Tremblant area between fall and spring to hunt and fish on the ice. In the 17th century, the region's watersheds made it easy for small Algonquin tribes-the Weskarini in the west and the Attikamek in the east-to reach the area. Today, the Amerindian legend responsible for the name "Mont Tremblant" [trembling mountain] is the most tangible evidence of their presence.

From 1895 to 1961, logging was the main activity in the park. In the late 19th century, small-scale logging companies sought out the largest fir and spruce trees for the American timber market. In the early 20th century, as the logging industry expanded and came to occupy almost all sectors of the park, then timber gave way to pulpwood, and the forests were divided up amongst more than forty logging companies. In 1932, three giants emerged to replace the small logging companies and share control of the area: Canadian International Paper to the west, Consolidated Bathurst to the east and E. B. Eddy to the north.

By floating felled trees down lakes, rivers and streams, the companies were able to use the region's physical geography - ahighly developed drainage system, mountainous terrain that accelerates waterflow and a spring thaw that produces flooding - to transport logs. With waterways shared by three drainage basins, the area was accessible to companies from the Lanaudière, Mauricie and Outaouais regions. These companies continued their operations until the late 1970s, despite the growing popularity of outdoor activities. Few traces remain today of their stone and wooden dams, fire lookout towers and rudimentary camps, designed to be used for only a few years, even months. Some buildings, converted into hunting and fishing camps by private clubs or outfitters, were used for a few years then torn down. However, many camping and picnic areas have since been created on the site of former logging and log-drive camps or named in their honour. A number of roads and trails in the area were once portages or roads cleared by loggers.

By the turn of the 20th century, several private hunting and fishing clubs had set up shop in camps abandoned by the logging companies and were taking advantage of the region's abundant game and wildlife. However, their hunting rights were revoked around 1958, leaving them to rely exclusively on fishing until the early 1970s, when they were shut down outright. A controlled moose hunt, organised by Quebec's Wildlife and Conservation Service, was opened to the public in certain sectors of the park from 1972 to 1979.

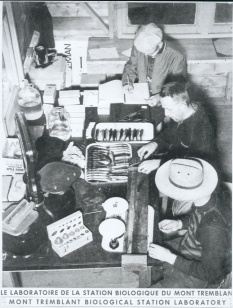

In the late 1940s, authorities across Quebec observed an increase in the number of people fishing, along with a decline in the populations of several species of fish. This discovery led the Office de Biologie du Québec to create the Station Biologique du Mont-Tremblant, a research centre housed in buildings once owned by Canadian International Paper.

From June to September of each year from 1949 to 1962, a group of about twenty biologists, chemists, physicists and technicians conducted research on the productivity and overall state of Quebec's rivers and lakes. These researchers laid the ground work for what could be called a scientific approach to managing sport fisheries and helped put Quebec on the map in the field. Given the diversity of its lakes and waterways, the park was a choice laboratory. In addition to its exceptional value to biologists, the park was also strategically located at the junction between the distribution ranges of northern and southern species. Along with aquatic wildlife specialists, the Station Biologique played host to scientists from all disciplines, including entomologists, ornithologists, botanists, paleobotanists and geographers.

The knowledge acquired by researchers at the Station, whose efforts were aimed at achieving the best possible use of resources, gave rise to a number of strategies for preserving the area's unique natural heritage. Studies on ways to better manage the use of fish species led to developments in the protection of Quebec's fresh water resources. The task of studying and developing lakes was later conferred to the Wildlife and Conservation Service, which resulted in the closing of the Station Biologique. As a new use for these resources (outdoor activities) emerged in the late 1950s, forests and waterways were increasingly promoted as prime locations for year-round recreation and leisure.

The Outdoor Era

Although the first steps towards a public park were taken in 1939, when permission was granted to create ski runs on Mont Tremblant, it wasn't until the late 1950s that the park was opened to the public, which was largely due to pressure from scientists at the Station Biologique.

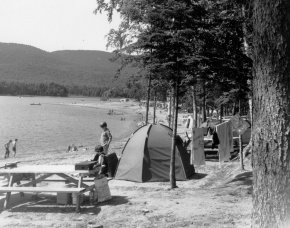

At the time, the region was booming; for following World War II, the area's road network began to expand to accommodate the increasing use of automobiles and the changing needs of urban populations. All these changes accelerated the development of the region's tourist potential. In the 1960s, the park, which was then renamed Parc du Mont-Tremblant, began contributing to the growth of the tourist industry. Visitors came to rest, swim, picnic, fish or stay at one of the park's many campgrounds. The construction of two additional roads helped further the development of the eastern part of the park. While the logging companies, private clubs and fishing outfitters all continued to hold on to their rights in the park, its recreational vocation was soon firmly established. In the early 1970s, land was bought back from the clubs and outfitters and new campgrounds, canoe-camping routes and hiking andcross-country skiing trails were created.

The Birth of the Conservation Era

Under the Parks Act, protecting and promoting Quebec's natural regions became the raison d'être of parks throughout the province. Thus, in 1981, Parc du Mont-Tremblant took on a role of conservation, education and recreation. At the same time, the exploitation of forest, mineral and energy resources became illegal. The park is now responsible for conservation and protection in the area, which is a representative sample of the geology, flora and wildlife of the southern Laurentian region (one of Quebec's 43 natural regions). It is also responsible for making the natural spaces more easily accessible to the general public for educational and outdoor activities. Amendments to the act in 2001 reinforced the mission of conservation held by the parks in Quebec, conferring on them the status of national parks.

Nonetheless, current interest in environmental protection has in no way diminished the public's love for the great outdoors. The park must therefore walk a fine line between preserving and promoting its natural resources, in order for visitors to enjoy themselves, while remaining in harmony with the natural environment.

Parc National du Mont-Tremblant

Today, the park covers 1,510 km2 [583 square miles] of land between Mont Tremblant and L'Assomption Valley, a landscape shaped by gentle mountains and dotted with lakes and clear rivers. Sugar maple and other deciduous trees abound, reminiscent of the province's southern woodlands, while the presence of fir trees attests to the proximity ofthe boreal forest.

A variety of wildlife thrives in the habitats created by the mountains and valleys, land and water: 202 bird species, 45 species of mammals, 34 fish species, 14 amphibian species and 6 reptilian species. Among the mammals that frequent the park's forest and aquatic habitats, the moose, white-tailed deer, black bear, beaver, Easternwolf, red fox, red squirrel and river otter best represent typical wildlife in the park and the southern Laurentians. The magnitude of the park's forests and river system is further embellished by an abundance of its most common bird species: the common merganser, common loon, great blue heron, ruffed grouse, black-capped chickadee and veery, along with seven species of woodpecker and twenty-seven of warbler common to the region's forests and underbrush. The presence of a number of rare species (fifteen rare types of vegetation and thirty rare animal species have been recorded to date) serves as a reminder of the importance of conservation.

All of the above-mentioned conservation initiatives are aimed at showing visitors what a national park really is: a part of our natural heritage that must be protected for future generations. This protection can be ensured by improving knowledge of the natural environment, by following the protection plan and by setting up a program for ensuring that ecological integrity is maintained and the environmental management plan is respected. Furthermore, the park's development policy is a quality one that unites the principles of preservation with park accessibility that allows for activities and services which encourage contact with nature through an educational program designed to arouse curiosity and raise awareness. This policy has been put into place in order to provide visitors with year-round recreational experiences, all while respecting the park's natural heritage.

Louise Cadieux

Park warden/naturalist, crew chief, Parc national du Mont-Tremblant

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Fournier, Marcel, Histoire du parc du Mont-Tremblant, des origines à 1981, Montreal, Ministère du Loisir, de la Chasse et de la Pêche, Direction régionale de Montréal, 1981, 91 p.

Laurin, Serge, Histoire des Laurentides (Les Régions du Québec, 3), Quebec, Institut québécois de recherche sur la culture, 1989, 892 p.

Morissonneau, Christian (Dir.), Guide de Lanaudière, Joliette, Conseil régional de la culture de Lanaudière, 1985, 327 p.

Soucy, Danielle, Lavallée de la Diable : de la hache aux canons à neige, new revised and expanded edition, Saint-Jovite, Éditions du Peuplier, 1995, 223 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

«Une journée avec les

huards», une a... -

Activité de découvert

e animée par un... -

Activité de découvert

Activité de découvert

e animée par un... -

Activités hivernales

au Mont-Trembla...

-

Bâtiments de la Canad

Bâtiments de la Canad

ian Internation... -

Camping de la Bacagno

le en 1966 -

Canot sur la Diable

-

Canotage à travers le

s méandres de l...

-

Castor

Castor

-

Cerf de Virginie mâle

Cerf de Virginie mâle

-

Entrée du secteur de

Entrée du secteur de

la Diable dans... -

Érables à sucre et ér

Érables à sucre et ér

ables rouges

-

Grands hérons au nid

Grands hérons au nid

-

La tortue des bois, u

La tortue des bois, u

ne espèce vulné... -

Laboratoire de la Sta

Laboratoire de la Sta

tion biologique... -

Le loup, l’emblème du

Le loup, l’emblème du

parc national ...

-

Paruline à gorge noir

Paruline à gorge noir

e -

Paysage hivernal des

Paysage hivernal des

hauts sommets -

Sentier du Lac-aux-At

ocas -

Vallée de la Diable v

ue du belvédère...

Vidéo

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Paysages emblématiques de Lac-Tremblant-Nord, un patrimoine naturel et culturel

- Station Mont-Tremblant

- Parc national du Mont-Tremblant