Assomption Sash

par LeBlanc, Monique

The Assomption (or arrow) sash is a symbolic piece of clothing central to the culture of the French-speaking population of North America. The item was widely worn for almost a century, from the end of the 18th to the end of the 19th century, before it fell into disuse, a result of the decline of the fur trade industry. Subsequently, this "masterpiece of Canadian domestic textile industry", as E.-Z. Massicotte once put it, came to be associated with the traditional cultures of the French-Canadian and the Métis. Today, enthusiasts have committed themselves to safeguarding of this cultural custom. Thanks to artisans who continue to weave sashes according to traditional methods, this unique technique has been kept alive.

Article disponible en français : Ceinture fléchée

A Living Tradition

In the past, the Canadian men would wore arrow sashes to stay warm and add a splash of colour to their coarse grey homespun coats. These days, for two weeks of every year, Bonhomme Carnaval proudly wears a magnificent traditional hand-woven sash. The Carnaval crowds imitate him, wearing their own sash-that is usually machine-woven in Asia. The official Voyageur [Canadian explorer-trapper] of Saint-Boniface, Manitoba's Festival du Voyageur, also wears the as a part of his costume, to honour of the voyageur forefathers who came from Lower Canada in the employ of fur-trading companies. Some folk dancers even weave their own sashes and singers and storytellers often proudly wear the sash during their shows.

In many regions of the Province of Quebec, artisans continue to weave the sashes using local homespun wool, just as women of the 18th century did. Others, such as the artisans of Lanaudière, use the laborious 19th century process, which involves dyeing, waxing and twisting strands of worsted yarn, a type of wool from Britain. Several books have been published instruct future generations on this technique. Experts offer conferences and demonstrations of the weaving process to the general public and school children, as well as to employees and visitors of heritage institutions, etc. Others tell the tale of the arrow sash, so as to keep the memory of this distinctive article of clothing's long history alive.

The Legacy of an Ancient Custom

During the earliest days of the colony, the settlers were too busy surviving and had little time to write about the world around them (NOTE 1). And for the few who did, objects from everyday life were not interesting enough to be written about. This explains why the earliest recorded references to the arrow sash worn by French-Canadian habitants [settlers] are found in the writings of foreign visitors.

In 1776, Thomas Anburey writes about Canadians (NOTE 2): "[...] their dress is made of a kind of coat and, when it is cold, they wear a sort of blanket which they fasten around their body with a worsted sash [..." In 1777, a German [probably Hessian] mercenary, staying in Saint-Anne-de-la-Pérade is more explicit in his comments: "[...] They wear a thick wool sash with long fringes around their hips and over their coat-they weave it themselves-these sashes are of a variety of colours, depending on the wearer's taste" (NOTE 3). Furthermore, he says that even the Governor of Lower Canada, Guy Carleton, took to wearing the warm and practical article of clothing when travelling in winter. Many more accounts of this sort are found in newspapers, travel books and in correspondence of the time.

A list of all fictional works mentioning it would be far too long to be written down. But this fact confirms the popularity of the sash and the sense of identity it gave to the Canadian habitant. It is however interesting to note that Philippe Aubert de Gaspé Senior, in Les Anciens Canadiens and his son in Le Chercheur de Trésor ou L'Influence d'un Livre both make mentionof the distinctive article of clothing. It is also mentioned by Alphonse Poitras in Histoire de mon Oncle, Louis Fréchette in Tipite Vallerand, Washington Irving in Astoria and The Adventures of Captain Bonneville, not to mention Major John Richardson in Wacusta, Pontiac's Conspiracy and William Henry Drummond in his poems Le Voyageur and Getting Stout. Even Jules Verne describes the characteristic sash in Famille-Sans-Nom. [the English title is: Family Without a Name].

Not only is it found in many works of literature, many painters have also given a prominent role to characters wearing the colourful sash in their works. Modest sketches, watercolours, and paintings eloquently testify of the presence and popularity of the arrow sash. At least 28 renowned artists have depicted Canadian men wearing the sash. Of all of them, Krieghoff is the most prolific (NOTE 4). It is largely due to all these references and depictions of the sash, as well as many others, that it has been possible to trace the many threads of the arrow sash's back through history.

From the Earliest Beginnings to the Decline of a Custom

No one knows for sure how and when the arrow sash was first invented. The wool sash itself, as well as certain number of common patterns can be found in a great many of countries. For example, research has shown that the chevron (the V and the W) is a universal design. It was found to exist in 6th century Japan, in Eastern Europe countries, in Scandinavian lands as well as in Israel and North Africa.

In North America, the presence of wool sashes dates back to the earliest days of New-France. In 1534, Jacques Cartier, while passing through the Chaleur Bay, gave one to an American Indian. This anecdote seems to discredit the belief the sash is of American Indian origin. Later, inventories taken of deceased settlers' possessions, as well as written accounts confirmed the presence of fabric sashes (wool, cotton, hemp and velvet) in the colony. During the 18th century, the wool sash was more and more commonly used. Nonetheless, it is not until British rule of Quebec, a little before 1776, that written sources begin to document the existence of the "Canadians' colourful sash." The appearance of this woollen sash resembles the arrow sash, but the designs were not quite that of an Assomption Sash.

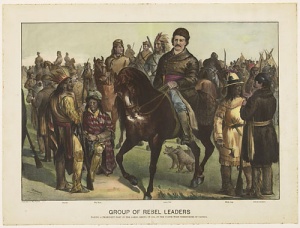

At the end of the 18th and at the beginning of the 19th century, the use of Canadian sash gradually spread to regions beyond the borders of Quebec, mostly to the West as a result the fur trade industry. The North West and Hudson's Bay companies supplied their men with the sashes and regularly offered them as gifts to First Nation peoples. Thereafter, the custom of wearing the colourful sash became more popular and widespread, particularly among the Natives. The article of clothing soon became the most important symbol of the Métis, a people that resulted from the meeting of voyageurs and Native women. They eventually created their own technique for weaving it, which was different from the method used by both the white settlers and the Native peoples. The image of Louis Riel, the legendary leader of the Métis, is so closely tied to the arrow sash that during the 1990 inauguration of the Winnipeg statue in his honour, one was tied around his waist. Today, the Order of the Sash is presented to people who have spent considerable effort in supporting the Métis cause.

In 1870, the fur trade industry collapsed. There was great poverty in the West and many Canadians and Métis moved south, particularly to Minnesota, Montana, Oklahoma and Oregon. They brought with them the knowledge of its weaving, which would then bepassed on before being lost. In British Columbia and Yukon, the arrow sash was worn by some of the first explorers and settlers. In an entirely different setting, at the end of the 18 century, a number of Natives from the Cree tribe from the Prairies fled their lands to settle in the Florida Peninsula. There, they mixed with Natives and former slaves from across the Deep South and came to be known as the Seminoles. Their wool sash tradition remained kept alive for a time. They wore the sash and so did many other Native tribes. Evidence of the widespread use of the arrow sash is occasionally discovered in all of the above-mentioned areas, whether it be in the attic of some family or the archives or storage of local museums.

An Artefact Present in Museums Across Canada

In Canada, many institutions still conserve the sashes of historic figures. The fact that such prominent figures wore it confirms the importance the article of clothing had over a large part of the continent. The Saint-Boniface museum showcases the sash of Jean-Baptiste Lagemodière, the first Canadian to settle on the Red River lands in 1806, as well as Louis Riel's and Bishop Fleury Deschambault's. Also, at Lower Fort Garry, Manitoba, visitors can get a glimpse of two more "famous" sashes. One is believed to have been worn by Sir George Simpson, governor of the Hudson's Bay Company from 1820 to 1860, and the other by Lord Strathcona, another director of the Hudson's Bay Company. Victoria's Royal British Columbia Museum exhibits the sash of James Douglas, the first governor of Vancouver Island. The Patriote Olivier Chénier's sash is kept in the Canadian Museum of Civilisation in Gatineau. Finally on his 1860 visit, the Prince of Wales offered a sash to Pierre Paul, the leader of the Micmac Nation. What remains of it is kept in Halifax's Museum of Natural History.

The Evolution of a Weaving Technique

While visiting the previously-mentioned museums (in addition to many others), as well as while observing and collecting avariety of samples of sashes, experts have noticed that the techniques used to make them has evolved over the years and from one weaver to another.

The first sashes, also called the coloured sash, which appeared shortly before 1776, had a chevron pattern (NOTE 5). At the end of the 18th century, the sash was still hand woven (no tools were used), but the designs became more sophisticated. Each strand is carefully placed to create arrow, lightning, diamond and square (chequered) patterns. As for the arrow designs, they began to be used around 1796. The first (mass) production of sashes began in England during the previous year. The country's textile industry would eventually supply the fur trade companies with sashes.

The local wool, produced and dyed by peasants, was gradually replaced by the worsted wool, first imported from England in 1800. In fact, the name worsted sash, often used by English-speaking authors of the time when speaking of the arrow sash, originates from the name of the wool. The arduous weaving process and a growing demand gave rise to the development of a multitude of techniques aimed at increasing production and lowering prices. Such was the case of the production of sashes in Britain, woven on looms starting in 1821, and the weaving operation in Sillery, where, starting in 1825, they are woven using shuttles. After 1835, Canadian production would mostly be concentrated in the Assomption region (NOTE 6). As a result, a particularly well known type of sash would be named after the region. Other cities, such as Granby, Chicoutimi and Lachute, would develop their own trademark patterns. Another important innovation was the invention of chemical dyes in England in 1856. They made it possible to fix colours that, up until then, would fade when exposed to the elements.

These various developments make it possible to determine a sash's age. The colours used also help experts determine when a sash was made because the choice of colours depended on what colour of wool was available at the time of arrival of the British boats during a particular period. For example, black was available only around 1801 and 1822 and light blue around 1819.

The Revival of the Technique

During the late 19th and early 20thcentury, the cultural custom of making and wearing the arrow sash went into decline with the final days of the fur trade industry (NOTE 7). Since then, many initiatives for the preservation and promotion of the sash have gradually taken place.

In 1907, Édouard-Zotique Massicotte, a folklore enthusiast and researcher, began to work towards raising the general public's awareness of the sash and its plight after having admired the work of a weaver invited by Canadian Guild of Crafts. In 1924, he published an article, in which he describes the arrow sash as a "masterpiece of the Canadian domestic industry". His colleague, Marius Barbeau, also became interested in the sash. He supervised the publication of a book on the matter; the management of this project he confided to Françoise Gaudet-Smet, a dedicated defender of Quebec artisan crafts. The Sisters of Providence, the Department of Agriculture and L'École des Arts Appliqués began offering courses on sash weaving in 1939. Unfortunately, the general public showed little interest.

It would finally be the initiative of Mrs Phidias Robert, an octogenarian from Saint-Ambroise-de-Kildare, that, in 1967 (NOTE 8), that would stimulate the public's interest on this unique form of weaving. Aware of the fact that she had valuable knowledge of a little known skill, she offered to teach others how to weave arrow sashes on the premises of a department store in East Montreal. When asked why she wanted to do this, she stated: "It will be my contribution to the Centennial Celebrations". The initiative went against the trends of the day. For, in 1967, Quebec was beginning to open up to the world more than ever and the arrow sash was a symbol of the traditional society that many were wanted to part with. Nonetheless, the event established ties between a few weavers from various regions of Quebec, as well as with others who had long forgotten the technique learned in their youth. Courses were offered and, as a result, new generation of sash weaving enthusiasts began to spread their knowledge all around the province. In the 1970s books were published by various artisans, as well as by Cyril Simard, the then director of a craft and trade organisation known as Centrale d'Artisanat. The popularity ofthis cultural custom fit right in with the widespread weaving trend (as well as the macramé rage) already in full swing at the time. This new dynamic produced various hybrid forms with mixed results:lamp shades, cushions and other objects that made liberal use of the design. Around that time, weaver Lucien Desmarais founded the Association des Artisans de Ceinture Fléchée du Québec [Arrow Sash Artisans' Association] in 1972. In 1984, the movement brought together around 500 artisans. Twenty years or so later, another association was founded in Lanaudière and the tradition was also passed on to a new generation by a few individualsin Western Canada.

Weaving the Assomption Sash in the 21thCentury

Production of the Assomption Sash is still alive today, although it is not a flourishing trade. Those who practice the custom do so out of passion, for the simple pleasure of creating magnificent sashes. The process requires much time, which explains the high price of a sash. Prices ranges from $ 500 to $ 4,000 depending on the grade of the wool and whether or not the weaver uses traditional techniques involving organic dyes and the twisting of wool strands on a spinning wheel. Not to mention the fact that buyers are not always aware of the subtleties that distinguishes a machine-woven item form a hand-made sash. Arrow sashes are thus highly sought after as collectibles and are often offered as formal gifts by corporations or government officials.

A recent trend consists in making the design more affordable, by selling smaller products that are made using the traditional methods. Thus, bookmarks, bracelets, hat bands and scarves range anywhere from around ten to a few hundred dollars. These new uses for the weaving technique enable a larger sector of the population to appreciate the arrow design. It is, after all, one of French-speaking North America's authentic contributions to the history of the world of weaving. It is an important tradition whose fame reaches beyond our borders. Its many forms and uses are as much a confirmation of its importance as it is of its originality.

Monique LeBlanc, Ph.D

Ethnologist

Artisan and specialist of the arrow design

NOTES

Note 1: J.C. Bonnefons, voyageur [trapper and explorer] in New France from 1751-61.

Note 2: Anburey, Thomas, Voyage dans les Parties Intérieures de l'Amérique, pendant le Cours de la Dernière Guerre, Paris, Briand, 1790, 2 vol. [French translation of Travels through the Interior Parts of North America].

Note 3: Free translation [of German original]: "Ihr Kleide ist um die Hüften mit selbs gemacht ein dicke Sharpen von Wolle gewirt, die, langer Broten haben ; diese Sharpen sind von allerlie farben nach eines jeden Phantasie." Anonymous, Vertraulich Briefe aus Kanada, Ste-Anne, 9 marz-April 1777, Eingelafen in Niedjadsen 1 aug. 1777, copy Public Library of Congress, Washington (D.C.) Eh.111 (Heft xv111) p. 137.

Note 4: In chronological order: Thomas Davies, GeorgeHeriot, Elisabeth Simcoe, James Peachy, Frederich von Germann, an anonymous Bavarian, Louis Dulongpré, Sempronius Strenton, John Lambert, Peter Rindisbacher, John Crawford Young, James Pattison Cockburn, Sir George Gipps, Sir Richard G.A. Levinge, Mary Millicent Chaplin, A.F. Dynely, Paul kane, W.H.Bartlett, W.H.E. Napier, William Armstrong, Cornélius Krieghoff, George Seton, James Duncan, Joseph Dynes, W.G.R. Hind, William Norman, E.J. Massicotte and Clarence Gagnon.

Note 5: See the watercolour by von Germann Ein Canadischer Bauer. [Canadian Farmer]

Note 6: Wade, Mason, L'Encyclopédie du Canada Français à nos Jours, 1760-1967, translated by Adrien Venne with the help of Francis Lubeyrie, Montreal, Cercle du Livre de France, 1963, 3 vol.

Note 7: Neering, Rosemary, Fur Trade, Growth of a Nation Series, Fitzhenry and White side, 1974.

Note 8: LeBlanc, Monique, Parle-moi de la Ceinture Fléchée! Fides, 1977. See p.46-47.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Association des artisans de ceinture fléchée de Lanaudière, Histoire et origines de la ceinture fléchée traditionnelle dite de l'Assomption, Sillery, Septentrion, 1994.

Barbeau, Marius, Ceintures fléchées, Montréal, Éditions Paysana,1945.

Bourret, Françoise et Lucie Lavigne, Le fléché, l'art du tissage au doigt, Montréal, les éditions de l'Homme, 1973.

Brosseau, Hélène Varin, Le fléché traditionnel et contemporain, éditions La Presse, 1980.

Hamelin, Véronique, Le fléché authentique du Québec par la méthode renouvelée, Outremont, Léméac, 1983.

Hemlin, Denise Verdeau, Évolution des motifs de fléché, Montréal,Association des artisans de ceinture fléchée du Québec, 1990.

LeBlanc, Monique, J'apprends à flécher, Montréal, René Ferron, éditeur, 1973.

LeBlanc, Monique, Parle-moi de la ceinture fléchée, Montréal, Fides,1977.

LeBlanc, Monique, Le tissage aux doigts, Paris, Solarama, 1981.

Leblanc, Monique, "Une jolie cinture à flesche", Sa présence au Bas-Canada, son cheminement vers l'Ouest, son introduction chez les Amérindiens Québec, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 2003.

Massicotte, É.-Z., La ceinture fléchée. Chef-d'œuvre de l'industrie domestique au Canada, Mémoire de la Société royale du Canada. Montréal, section 1, série 111, vol. xviii, mai 1924.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affiche du Festival d

e Lanaudière -

Affiche du Festival d

e Lanaudière (d... -

Ceinture servant à l’

interprétation... -

Ceintures produites p

ar Jocelyne Ven...

-

Chasseur indien

-

Confection d’un foula

rd en grosse la... -

Échantillons de chevr

ons -

Exemples de ceintures

traditionnelle...

-

Le Raquetteur

-

Mme France Hervieux,

artisane en flé... -

Mme Gisèle Brassard a

Mme Gisèle Brassard a

u Saguenay, ave... -

Mme Jocelyne Venne, a

rtisane en fléc...

-

Mme Yvette Michelin,

Mme Yvette Michelin,

artisane de Qué... -

Mme Yvette Michelin,

Mme Yvette Michelin,

artisane de Qué... -

Napoléon Laliberté. I

llustration pou... -

Noeuds

-

Pièces servant à prés

enter le fléché... -

Présentation d'un che

f nouvellement ... -

Quatre fêtards à Québ

ec -

Rubans de médailles