Mount Royal: The Importance of Civic Engagement

par Guilbault, Sylvie

Mount Royal is part and parcel of Montreal’s history and identity. Dominating the city, “the mountain,” as Montrealers affectionately call it, has traditionally been—and continues to be—a geographical landmark and heritage symbol melding nature, culture and history. At 232 meters in height, the small Monteregien Hill named by Jacques Cartier in 1535 in honour of the King of France, and coiffed with a cross by de Maisonneuve in 1643, has long held a special place in the hearts of Montrealers. Their indefatigable efforts to protect it over the past 150 years testify to its powerful defining influence. And their civic engagement also bears witness to the key role that the public can play in preserving and promoting our collective heritage.

Article disponible en français : Mont-Royal: importance de l’engagement citoyen

The Creation of Mount Royal Park

Since 1850, people’s perceptions and attitudes with respect to the mountain have changed as society has evolved.

In the early 19th century, Montrealers began to see the mountain as an antidote to the “urban poison” spawned by the city’s rapid growth and the pollution, hygiene and sanitation problems it engendered. Residents of the city, whose population exploded between 1810 and 1850, began visiting Mount Royal in increasing numbers to enjoy a stroll or a picnic, activities tolerated by the orchard owners there. The Mount Royal and Notre-Dame-des-Neiges cemeteries, founded respectively in 1852 and 1854, were used in a similar manner.

During an especially harsh winter in the 1860s, a certain Mr. Lamothe, one of the mountain’s landowners, decided to cut down all the trees on his property for firewood. Citizens scandalized by the move, and worried about the fate of Mount Royal’s other forested areas, launched a campaign of public assemblies and petitions urging the City to create a park. In the face of public pressure, the City agreed, and between 1869 and 1875, it spent $1,000,000—a very considerable sum for the times—to acquire various parcels of private land. Some of the money also went to pay for the planning and design of Mount Royal Park, one of the first great urban parks in Canada. Frederick Law Olmsted, the renowned American landscape architect, was chosen to draw up the plans and lead the work.

Defending the Park and the Mountain

The official opening of Mount Royal Park in 1876 did not, however, mark the end of Montrealers’ civic engagement. Far from it. As the city continued to grow up and around Mount Royal, citizens remained vigilant as to the mountain’s fate. Action and awareness campaigns conducted since 1895 illustrate different phases of this public mobilization. Initially focused on the park, they expanded in scope in the early 1960s to encompass the entire mountain.

In 1895, 20,000 women signed a petition under the name of the Park Protective Society to prevent the construction of a tramway running past the cemeteries along the side of the mountain (a project that did eventually see the light 25 years later). This group gave birth to the Montreal Parks and Playgrounds Association. For nearly 60 years, the Association acted as an advocate for the protection and creation of parks in Montreal. Among its many battles, it fought development of all forms of commercial recreation in Mount Royal Park and also opposed the closure of the funicular railway, a move that would deny many Montrealers access to the summit. It also joined forces with Les Gardiens de la Montagne, another citizens’ group founded in 1934, to lead a fierce battle against the opening of the park to automobile traffic.

In 1959, 28 associations, including the Montreal Parks and Playgrounds Association, campaigned against a project to build 16 apartment buildings on property belonging to the Mount Royal Cemetery. After the project was abandoned in response to the campaign, the City of Montreal purchased the property and incorporated it into the park. Up until the late 1950s, acquiring land for the park was the most common approach used to protect the mountain.

By the mid-20th century, however, the mountain, with its numerous private properties, major hospital and university institutions and cemeteries, churches and schools, had become a much more complex area to protect. In response, citizen action increasingly focused on controlling development through the enforcement of zoning regulations and planning criteria. In 1960, the Citizens’ Planning Committee for Mount Royal launched a wide-ranging debate on the future of the entire mountain. It lobbied municipal and provincial authorities to expand the park and prevent new construction on neighbouring land. It also called for a ban on the construction of tall buildings in the urban zone adjacent to the park and for the creation of a body tasked with implementing, enforcing and monitoring these new rules. The Committee urged the three municipalities with jurisdiction over Mount Royal—Montreal, Outremont and Westmount—to move in this direction. In 1975, the Committee’s efforts led to an amendment to Montreal’s City Charter, which extended park zoning to the institutions adjacent to the mountain: Royal Victoria Hospital, McGill University, Université de Montréal and the Notre-Dame-des-Neiges and Mount Royal cemeteries.

An Increasingly Assertive Citizens’ Movement

The comprehensive vision championed by the Committee became increasingly well articulated in the mid-1980s, rallying the mountain’s defenders at a time when major infrastructure projects were being announced, including a communications tower, tourist facilities in Mount Royal Park, and a downhill ski area on the north side of the mountain. Citizens and heritage organizations like Héritage Montréal and Sauvons Montréal vehemently denounced these projects. In the wake of this latest battle, a new organization dedicated to Mount Royal’s protection—Les Amis de la Montagne—was born in spring 1986. This new organization drew its expertise, strength and influence from the collective involvement of numerous associations and citizens committed to protecting Mount Royal.

In a manifesto entitled Le mont Royal, fierté des Montréalais (Mount Royal, the pride of Montrealers), Les Amis de la Montagne called for proper maintenance of the park—which was in a pitiful state—and protection for the rest of Mount Royal. Additional recommendations included development of a master plan for the entire mountain, further expansion of the park and the creation of a management body tasked with coordinating improvement projects and ensuring public representation.

Les Amis de la Montagne works exclusively to protect Mount Royal by fostering community engagement, thereby perpetuating the vision and work of its predecessors. The commitment to education and community engagement spawned by the mountain is still expressed through the broad network of organizations active on issues like the environment, heritage protection, history, culture, urban planning and landscape architecture. In their own way, each of them carries on the education, research, and civil action traditions that have benefited the mountain over the years.

By pooling their energy, these organizations hope to achieve the recognition and budgets necessary to maintain, protect and enhance the mountain. In 1987, the City of Montreal designated part of Mount Royal a “heritage site.” The Quebec government followed suit in 2003 when it recognized the mountain as a “historic and natural district,” the first-ever designation of this kind in the province. In addition, since the early 1990s, all projects involving the mountain have been subject to the vision and criteria set forth in the Mount Royal Protection and Enhancement Plan, which was adopted by the City of Montreal after extensive public consultations.

With the founding of Les Amis de la Montagne, civic engagement also took a new turn. In addition to acting as a watchdog to ensure public authorities meet their responsibilities, the organization also gives citizens, philanthropic foundations, and private companies an opportunity to actively contribute to Mount Royal’s protection and enhancement. To date, thousands of volunteers and donors have pitched in to help improve and enhance the mountain through annual clean-ups, numerous tree-plantings, animal and plant research and conservation patrols. Generous donations and sponsorships have funded building and infrastructure maintenance, as well as events like the Célébration des Tuques Bleue, a snowshoe climb that attracts close to 800 people every year with the revival of a tradition over a century old.

Conclusion

Citizens have always played an important role in protecting Mount Royal, either by bringing pressure to bear on public authorities or by getting directly involved in planning and enhancement. This remarkable example of over 150 years of civic engagement may be unique in North America. Mount Royal’s importance as a city asset is undeniable, yet even today, at a time when citizens everywhere are concerned about their environment and the quality of life in the city, nothing can be taken for granted. Despite the protective statutes now in effect, real estate developers continue to covet part of the mountain, while certain hospitals, cemeteries and universities starved for space seek permission to expand their facilities. Although municipal and other government officials are now the custodians of this collective heritage, history shows how important public vigilance has been in ensuring that this small hill, with its rich history, nature and culture, remains the pride of Montrealers of all generations.

Sylvie

Guilbault

Executive Director, Les Amis de la Montagne

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Revue Continuité, numéro 90. Texte de Dinu Bumbaru, directeur des programmes, Héritage Montréal et de Sylvie Guilbault, directrice générale, Les Amis de la montagne. Automne 2001.

Mémoire de maîtrise de Nathalie Zinger. Faculté d'aménagement de l'Université de Montréal. 1990.

Les quatre saisons du Mont Royal. Oswald Foisy et Peter Jacobs. Éditions du Méridien. 2000.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Affiche «Espaces vert

Affiche «Espaces vert

s pas à vendre»... -

Affiche «Montrez votr

Affiche «Montrez votr

e attachement a... -

Affiche contre le pro

Affiche contre le pro

jet de tour sur... -

Affichette du Mois du

Affichette du Mois du

Mont-Royal 200...

-

Belvédère Kondiaronk,

2008 -

Belvédère Kondiaronk,

2008 -

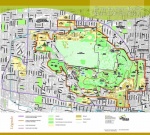

Carte du Mont-Royal,

Carte du Mont-Royal,

2009 -

Carte postale ancienn

e montrant la r...

-

Cimetière du Mont-Roy

al, 2009 -

Cimetière juif, sect

ion des communa... -

Colvert en milieu hum

ide, Mont-Royal... -

Construction du stati

Construction du stati

onnement près ...

-

Construction du tunne

Construction du tunne

l -

Corvée du Mont-Royal

Corvée du Mont-Royal

-

Cours de ski Jackrabb

Cours de ski Jackrabb

it, Mont-Royal -

Départ de la course 2

Départ de la course 2

009 des Tuques ...

-

Effets de la crise du

Effets de la crise du

verglas de 199... -

Fontaine de la rédemp

Fontaine de la rédemp

tion, oratoire ... -

Groupe scolaire sur l

e Mont-Royal -

Image ornant le chand

Image ornant le chand

ail «Mai, 2009:...

-

Logo officiel des Ami

Logo officiel des Ami

s de la montagn... -

Logo officiel du 125e

Logo officiel du 125e

anniversaire d... -

Maison Smith, abritan

Maison Smith, abritan

t l'association... -

Manifestation lors de

Manifestation lors de

la fête champê...

-

MUHC Allan Memorial H

ospital, 2008 -

Personnages en costum

Personnages en costum

es évoquant le ... -

Personnages historiqu

Personnages historiqu

es, 125e annive... -

Plan de protection et

Plan de protection et

de mise en val...

-

Plan du parc du Mont-

Plan du parc du Mont-

Royal en 1877 -

Promeneurs dans le pa

rc du Mont-Roya... -

Sentier du chemin Olm

stead, Mont-Roy... -

Sentier du parc Summi

t, Mont-Royal, ...

-

Thé lors de la fête c

Thé lors de la fête c

hampêtre marqua... -

Tramway, Mont-Royal,

Tramway, Mont-Royal,

1959 -

Tuques Bleues - repas

au chalet 2008 -

Tuques Bleues - site

départ 2010

-

Vitrail «Tuque bleue»

Vitrail «Tuque bleue»

du club sporti... -

Voie Camilien-Houde s

Voie Camilien-Houde s

ur le Mont-Roya... -

Vue aérienne du campu

Vue aérienne du campu

s de l'Universi... -

Vue aérienne du cimet

Vue aérienne du cimet

ière du Mont-Ro...

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Vue de Montréal depuis le mont Royal, exposition virtuelle du Musée McCord

- Parc du Mont-Royal, exposition virtuelle du Musée McCord

- Sacrée montagne. Flâneries interactives autour du mont Royal (par l'Office national du film)