La Mauricie National Park of Canada

par Gourbilière, Claire

La Mauricie National Park was created in 1970 to protect and develop the rich natural heritage that characterizes the southern Laurentians. Rising from ancient bedrock, the contoured mountains are covered by vast mixed forests, dotted with nearly 150 lakes and rich in wildlife. In ages past, aboriginal peoples travelled through the region, hunting and fishing for food and, later, taking part in the fur trade. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the area was the site of intensive logging. Beginning in the 1880s, the region also became a travel destination for rich sports fishermen, with the establishment of several fish and game clubs. Today La Mauricie National Park serves as a refuge for many species of wildlife, including the Eastern wolf, the black bear, the beaver, the moose and many species of fish. Visitors can enjoy many outdoor activities in the park and discover the quiet beauty of nature.

Article disponible en français : Parc national du Canada de la Mauricie

History Seen Through the Landscape of La Mauricie Park

La Mauricie National Park is an area representative of the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence Precambrian region. Located on the north shore of the St. Lawrence, it is bordered to the east by the Saint Maurice River and to the north by the Matawin River. The park covers an area of 536 km2, 93% of which is mixed forest composed of conifers and deciduous trees. Most of the area is reserved for plant and wildlife conservation programs. The 200,000 or so annual visitors to the sectors open to the public come to the park to enjoy outdoor activities and to discover nature.

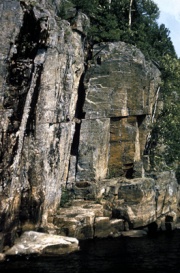

Evidence of the geological movements of the past is easily seen in the park. The rock formations of the Laurentians, composed of metamorphic rock, are among the oldest in North America (ten times older than the Rockies). The most common rock is gneiss, its pink and grey outcroppings blending perfectly with the green of the park's vegetation. The land contours of the region seen today are the result of glaciation; during the final glacial period that peaked 20,000 years ago and ended about 10,000 years ago, the last glaciers rounded the mountain tops and deepened the valleys. As they receded they left debris in their path, along with the huge erratic rocks (NOTE 1) now scattered over the landscape. Glacial till (NOTE 2) and fluvioglacial deposits held back the glacial meltwater, resulting in the formation of a string of many interconnected lakes running through the park's three main valleys. The lakes vary in size and shape, from small round basins to more elongated bodies of water like the seventeen-mile-long Wapizagonke Lake that winds its way through a narrow valley, its shoreline consisting of both rocky escarpments and sandy beaches. The park's river system can be divided into three main watersheds: the Saint Maurice River basin (NOTE 3), the Matawin River basin and the Shawinigan River basin.

Numerous trails and lookouts throughout the park allow visitors to observe the land forms that provide the foundation for the landscapes of La Mauricie Park. One of these lookouts, Le Passage, provides a view out over a narrow valley with sandy banks winding through sharp cliffs and disappearing into a distant ancient plateau, covered in rolling forest as far as the eye can see. A transitional forest between the northern boreal and the southern deciduous forest, it is composed largely of sugar maple, yellow birch, red spruce and white pine. Overall, the vast forested area includes at least twenty species of deciduous trees and ten or so species of conifer.

The park provides diverse habitats suitable for a variety of wildlife. One of the most common mammals is the moose. The black bear is also common, attracted by the mixed stands of sugar maple and beech trees. Two packs of Eastern wolf (NOTE 4) live in the park. Coyotes are found mainly in the south, near the farms along the park boundary. The American marten and the red fox share the park habitat, while otters and beavers move along the shores of the lakes and rivers. In the air, about 180 bird species have been observed, including the common loon, which is the park's symbol, and a number of species of raptor. The aquatic wildlife includes twenty-four species of fish, only four of which are indigenous to the area. Two of these native species are the Artic char and the brook trout (speckled trout). On the ground and in the water, twenty species of reptile have been recorded, including one of the northernmost populations of wood turtle, designated as a threatened species in Canada.

Land of Nomadic Peoples

Over the centuries, people travelled through the area now covered by La Mauricie National Park. Those who lived there did so only temporarily, never establishing any permanent settlements.

Nomadic people belonging to the Algonquin Nation travelled through the park, as evidenced by the numerous remains they left behind, such as the stone implements found on the shores of Wapizagonke Lake and the 2,000-year-old red-ochre paintings on rock walls in the park. These Amerindians were subsistence hunters, fishermen and gatherers, known for their birch bark canoes. Sometimes called "coursers of the waterways", these canoes had a cedar frame, covered with birch bark sewn together with pine roots. Spruce resin was used to waterproof the vessels. These people were decimated over a period of a few decades by disease and by war with the Iroquois; they are no longer referred to in documents written after 1660. However, they were involved in the fur trade with the French in the first half of the 17th century and this lead to the establishment of the Trois-Rivières trading post. For a long period, the Saint Maurice River ("Attikamek Sipi" in Algonquin) was the main access to park land.

Intensive Logging

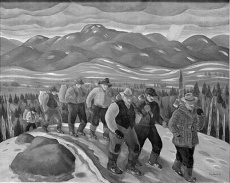

Logging began in the La Mauricie Park area in the early 19th century, due to an increased demand for lumber in England. In the beginning, only certain trees were logged and, during this period, most of the old-growth red and white pines were cut down and sent to saw mills. This continued until 1925, when the cutting of large fir began. By the beginning of the 20th century, there were few trees left large enough for lumber. At this time, the pulp and paper industry arrived in search of pulpwood, the essential ingredient in the manufacture of paper pulp. This new industry made La Mauricie the world leader in the production of newsprint and provided many jobs in pulp mills located near Saint Maurice. Logging ended in the 1950s but, in some parts of the park, considerable evidence of its existence can still be found: old dams, remains of logging booms, square-timber camps, etc.

Cutting down trees was not the only way in which human activity affected the park's vegetation. Between 1930 and 1932, the Laurentide Paper Company planted several thousand acres of white spruce on abandoned farmland, 1,053 acres (426 hectares) of which are now within the boundaries of La Mauricie Park. Also, many forest fires, often started by humans, burned large and small tracts of forest between 1910 and 1954. Very few forests in the national park remain unscathed by the effects of human activity or the consequences of fire.

The Establishment of Private Fish and Game Clubs

At the end of the 19th century, the excellent fishing in the area led to the creation of prestigious fish and game clubs. Rich Canadians and Americans came to fish for Artic char or to hunt the woodland caribou that lived in the park at the time (NOTE 5). This is how the first big private clubs began in the future La Mauricie National Park: the Shawinigan Club in 1883 and the Laurentian Club in 1886. These clubs played a major role in wildlife protection by preventing overuse of the resource. However, the introduction of several species of fish into the lakes disturbed and permanently changed the aquatic ecosystems. In 1970, sixteen such clubs operated on what is now park land. Their activities ceased when the park was established. Today, the Wabenaki and Andrew Lodges recall their existence. The former was the members' dining room and the latter, the home of the manager of the Laurentian Club, which also had several other buildings and a huge vegetable garden. In 1952, the establishment was sold to the City of Shawinigan Falls, which leased them to the Wabenaki Fish and Game Club. The Wabenaki and Andrew Lodges became federal property in 1972 and were classified as heritage buildings. They continue to be used today as accommodation for park visitors, a magnificent example of how historic buildings can be restored and re-used.

Protecting an Area Changed by Human Activity

The creation of La Mauricie National Park in 1970 put an end to a century and a half of logging activity. Since then, the forest has been regaining its rightful place and, over time, former logging roads are disappearing, like old wounds that heal over. The riverbeds and lake bottoms, used in the past for log driving, are gradually being restored, as well. In 2005, the park initiated the "Log to Canoe" project to restore the aquatic environments of a dozen lakes to their natural state.

The role of all parks in the national park system is to protect areas representative of one of the thirty-nine natural areas of Canada. The Parks Canada objective in La Mauricie National Park, as in all other parks, is "to protect representative natural areas and to encourage public understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of this natural heritage". The ultimate goal of its activities is to maintain in an unimpaired state the natural heritage protected by its network of parks for future generations so that they, like those who have preceded them, may canoe on lakes full of fish, admire the beauty of the landscape fashioned by time, or listen to a wolf howling at the full moon. Consequently, the removal of natural resources from La Mauricie Park is prohibited. Fishing is allowed on twenty-eight lakes but it is highly regulated; it is meant to provide a "meeting place" where visitors can feel a sense of connection to nature. Hunting and trapping are not allowed. The main goal of park management and development is to ensure that processes are followed to allow the natural evolution of various ecosystems. The controlled burn program, established to promote the regeneration of the forest, and in particular of the white pine, is one example of such a process. On average, a team of specialists oversees the burning of fifty hectares of forest each year. The principle of ecological integrity, a concept developed by Parks Canada for the management of its parks, guides all actions taken in the park.

During the summer season, most public educational and recreational activities take place in or around the water. Three-quarters of the 200,000 annual visitors come to the park between June and September to camp, canoe, fish or swim. The remainder prefer to stay on dry land, hiking or mountain biking through the forest. An interpretation program, based on Laurentian heritage, was developed in the park to help visitors understand and appreciate the area. The program touches on the geological history, the human occupation and the various natural environments of the park. At the Saint-Jean-des-Piles Visitor Reception and Interpretation Centre, visitors can obtain information as they enter the park: models, brochures, exhibits and a 3-D slide show provide an interactive presentation of the park's history and its natural environment. A hall adjacent to the reception centre regularly exhibits the work of local artists. Other interpretation activities are available to the public in various other places throughout the park. Once the snow falls, winter sports enthusiasts can enjoy a network of eighty kilometres of cross-country ski trails and seventeen kilometres of snowshoe trails.

Since 1988, there has been a resurgence of efforts to protect and restore ecosystems and the park's natural heritage. A program of ecological surveillance, with several objectives, has been designed. There are a number of different conservation strategies; one of note is the program for the protection of the wood turtle population. In order to follow their movements, radio-transmitters have been placed on about twenty of these tiny reptiles, classified as threatened species in Canada. Egg-laying sites are identified to ensure that the reproductive cycle will not be disturbed by visitor activities.

La Mauricie National Park is dedicated to the conservation of nature and the appreciation of the history and natural heritage of the La Mauricie region. It not only attracts visitors, it also raises their awareness of the importance of protected areas.

Claire Gourbilière

Fifth-year student at the École nationale d’Ingénieurs de l’Horticulture et

du Paysage (France)

Specialization: Ingénierie des Territoires.

Acknowledgements to Albert van Dijk, Resource Conservation Manager, La Mauricie

National Park, as well as

to his colleagues in the park.

NOTES

1. Relatively large rock fragments. Erratic blocks were carried by the glaciers, sometimes over very large distances, and then dropped when the glacier melted.

2. The thickness of till ranges from tens of centimetres to several meters.

3. The longest waterway is the Saint Maurice River, which runs for twenty-four kilometres through a very steep valley.

4. Species at risk according to COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada).

5. Woodland caribou have not lived in the area since 1920.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Boucher, T., Mauricie d’autrefois, Éditions du Bien Public, Trois-Rivières, 1952, 206 p. (Coll. « L’Histoire régionale », no 11.)

Hardy, R., N. Seguin et al., Histoire de la Mauricie, Les Presses de l'Université Laval, 2004, 1139 p.

Lalumière, R., et M. Thibault, Les forêts du parc national de la Mauricie, au Québec, Québec, Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 1988, 495 p. Études écologiques, 11.

Parcs Canada, Messages d’importance nationale, Parc national de la Mauricie, Ottawa, Parcs Canada, 1979, 20 p.

Parcs Canada, Plan directeur, version abrégée, Service d’interprétation, Parc national de la Mauricie, 2005, 23 p.

Parcs Canada, Le parc national de la Mauricie, un lieu de rencontre avec les Laurentides, Ottawa, Patrimoine canadien, 1995, 63 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Bâtiment du lac Édoua

Bâtiment du lac Édoua

rd du Club Laur... -

Intérieur du bâtiment

Intérieur du bâtiment

du lac Édouard... -

L'exposition permanen

L'exposition permanen

te du centre d'... -

La salle d'accueil de

La salle d'accueil de

s groupes et de...

-

Suivi de la populatio

Suivi de la populatio

n d'ours noirs -

Tortue des bois

Tortue des bois

-

Visiteurs au centre d

Visiteurs au centre d

'interprétation... -

Vue éloignée de l'usi

Vue éloignée de l'usi

ne de la Lauren...