The Old Port of Montréal

par Desjardins, Pauline

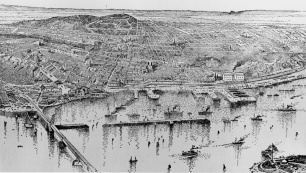

Montréal’s port has been an important link in the economic and social history of Canada since its foundation. The many examples of its rich heritage attest to its constant evolution – first as a place of transit and then later as a port of entry to the West – from the arrival of the first Europeans up till the present day. The port’s features have been adapted over the centuries to meet the ever increasing economic and technological needs. It has gone from being a natural harbour for beaching vessels to an international port. This heritage site is now part of the Old Montréal historic district and of the Lachine Canal National Historic Site of Canada.

Article disponible en français : Vieux-Port de Montréal

From a natural harbour to an international port

The Island of Montréal could only be reached by canoe or boat in the first two centuries after Europeans settled there. As such, the Old Port made an important contribution to the city’s early development. Rail transportation was added in the 19th century when the Victoria Bridge was built. However, it was only when cars, trucks, and planes began to be used that the pre-eminence of the Seaway started to gradually decline.

The first Europeans settled in the low lands on a point that was easily reached by small craft and that is now known as Pointe-à-Callière. It was not long before they moved to Coteau Saint-Louis (now Old Montréal) to avoid flooding. This elevated section was protected from the fury of the St. Lawrence River by a natural embankment that rose 5 to 6 metres above the beach.

Fortifications were soon built around the town, with the main gate opening onto the shore at the mouth of the Petite Rivière Saint-Pierre (little St. Pierre river). The port was situated between this area, identified as the “landing place,” and Îlot Normand, a small island in the harbour. Quays were already being built by the early 18th century. The first were rather rudimentary and were regularly carried off by the spring ice flow. More permanent structures were built near the end of the 18th century. Some of these structures, such as retaining walls made of wood and stone, were found in the late 1980s during the archaeological digs that preceded the construction of Montréal’s archaeological and historical museum, Pointe-à-Callière. This new institution, inaugurated in 1992, showcases both the history and archaeological remains of this historic site.

The city’s and port’s vocations changed during the 19th century. Their needs evolved as the economy became more diversified and immigration increased. By the end of the 18th century, merchants were beginning to feel cramped inside the fortifications and pressured the government to “knock the old walls of the city down.” The demolition of the defensive structures, beginning in 1802, created an east-west axis that was a precursor to de la Commune and Place D’Youville Streets, along which stores and warehouses were built to take advantage of maritime commerce. A customs office was likewise built to oversee import-export and immigration. The long, sinuous shape of the port is uncommon in North America and has remained relatively intact, despite modifications here and there.

A commission was created on March 26, 1830 to improve and expand the Harbour of Montréal. The Port Commissioners set up the infrastructures that gave the port the appearance that it kept all throughout the 19th century.

A stone wall was soon built along the river bank to reinforce the natural embankment. This wall marked the edge of the property of the Old Port of Montréal Corporation, a boundary which is still in effect today even though it is situated in de la Commune Street. The quays built below were erected on pine and later oak piles. As of 1846, the quays were replaced by timber cribwork structures that were stronger and, more importantly, easier to repair. The lifespan of these quays was evaluated at approximately 20 years. During this period, goods were kept directly on the quays and in nearby warehouses in the city. At the same time, the deepening of the channel in Lake Saint-Pierre and around the quays opened the port up to ocean going ships. The port was extended primarily toward the east, with the older sector maintaining the same layout.

The appearance of the port changed in the second half of 19th century, particularly with the arrival, in 1871, of rail transportation in the lower quays and of the first grain elevators in Faubourg Québec (1885). As of 1857, floating grain elevators, which were precursors to the modern self-unloading systems, were used to transfer wheat from river-going to transatlantic ships. Temporary warehouses, which were taken down every autumn, were set up for passengers and goods needing protection from the weather. Artificial lighting was brought to the quays in 1851. The lamps, which first ran on oil, then gas, and then electricity, considerably extended the working time.

By the end of the 19th century, Montréal had become an important transportation centre, its port infrastructure providing a direct link between maritime and rail transportation. With the new demands, the port underwent a transformation phase that was as radical as the one that occurred between 1830-1858, gradually taking on its current form. The new jetties were built entirely out of timber cribwork. As for the quays running along the promenade, a concrete wall was built on top of the underlying cribwork. The cribwork is sometimes visible below the concrete walls when the river level is low. The cribwork of the jetties is likewise still present behind the cylindrical concrete piles installed around 1950.

The heightening of the quays provided better protection against flooding and ice, while the large parallel jetties made for greater docking possibilities for ocean liners. The higher quays likewise made it possible to construct permanent buildings such as sheds and grain elevators. Some of these became symbols of modern architecture; the photo of elevator 2 below appeared in numerous international engineering and art publications in the first half of the 20th century. Elevator 5 represented one of the main examples of industrial machines that would become obsolete with the arrival of new transfer technologies. As for the sheds, more than eighteen were built during this period.

Another flood prevention wall was built to put a stop to the devastating effects of ice and flooding. This new wall was built a bit farther south than the preceding wall, near de la Commune Street. It completed the dyke erected in 1891, initially known as Guard Pier, then MacKay Pier, and now Cité du Havre. Once the flood wall was built, the gigantic port was cut off from the city and became a limited-access area. Two sections of this wall are still visible: to the east, between Bonsecours Street and Berri Street, and to the west, between McGill Street and the bridge on Mill Street.

The opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway in 1959 gave transatlantic ships direct access to the Great Lakes, bringing the mandatory transfer of merchandise at Montréal to an end. The decrease in cereal shipping and the diversification of products led to new handling methods. Containers and direct ship-to-ship transfer gradually reduced the need for grain elevators and large warehouses. The need for space to store and handle containers led the port authorities to fill in the Jacques-Cartier Basin and the downstream entry of the Lachine Canal, thereby closing it to through navigation. In 1979, elevator 2 and several outlying sheds – primarily those on the esplanade and the Jacques-Cartier and Clock Tower quays – were demolished.

From an international port to an urban port … historic

When heritage protection started to become an important social movement during the 1960s, land-use projects for the Old Port were caught between two opposing viewpoints: the reorganization of the sector by the Port Authorities and the classification of the Old Montréal area as a “historic district” by the Ministry of Cultural Affairs.

In November 1981, the federal government created the Old Port of Montréal Corporation, mandating it to revitalize and redesign the oldest area of the port. The first changes opened the port up to the river, in particular with the demolition of elevator 1.

From 1981 to 1984, the redevelopment was based on an urban park concept. This led to the creation of the basin in the central sector in place of elevator 1. The quays were also solidified, the Clock Tower was repaired, and the police station and cold-storage warehouse were gutted with the intention of eventually restoring them. Excavation was likewise begun on locks 1 and 2 of the Lachine Canal to open them up once again to navigation.

In 1984-1985, a large public consultation was held to determine public expectations so that a plan could be drawn up for the redevelopment of this undeniably historically important site. The new layout resulting from the master plan submitted in 1990 won numerous prizes in fields as wide-ranging as architecture, heritage conservation, maritime restoration, urban planning, landscape architecture, museology, and tourism.

Today, the Old Port of Montréal is a 50 hectare (123.5 acre) riverside park corresponding to the oldest section of the Port of Montréal. This lively area, which serves as a backdrop for various tourism activities, has been separated from the commercial port which continues to grow, particularly downstream of the Old Port, over tens of kilometres along the shoreline.

More than 5 million people per year go to the park, which was inaugurated in 1992 during the 350th anniversary of the founding of Montréal. Most of the visitors are from the greater Montréal region. They come to see the interactive exhibits at the Science Centre, the IMAX/TELUS movie theatre, and the numerous educational and cultural events, as well as the cruise ships, the winter ice rink, the promenade, and the St. Lawrence River.

The limits of the port are formed by large jetties sticking out into the river that were built in the early 20th century and that form large basins between them. Among them are: the Alexandra Basin, where the large international cruise ships dock; the King Edward Basin, which serves as a winter port for lakers; the Jacques-Cartier Basin, which is the port for local cruise ships, river shuttles, and river going visitors; the partially filled-in Bonsecours Basin, where people go around the vestiges of jetty 2 in pedal boats in summer and on skates in winter; and the Clock Tower Basin, an enclosure formed by an L-shaped jetty where the Montréal Yacht Club moors.

Some of the large sheds, which have welcomed several generations of passengers as well as all sorts of merchandise, are still standing on the quays. Some have roughly the same appearance as in their earliest years whereas others have been entirely renovated. A few iconic buildings are still on the quays. To the east stands the Clock Tower that was restored and designated in 1996 as a “classified federal heritage building”; to the west, the famous elevator 5 designated in 1996 as a “recognized federal heritage building” awaiting conversion; and, in the centre, the conveyor belt tower awaiting restoration.

The Old Port opened in 1992, at the same time as the Pointe-à-Callières Museum, and since then the number of visitors has not stopped growing. The Montréal Science Centre, inaugurated in 2000 in the renovated sheds on King Edward quay, is another key Montréal institution established on this major historical site.

Pauline

Desjardins

Ph.D, anthropologist-archaeologist

Specialist in industrial archaeology

Bibliography

Collectif, « Dossier : Patrimoine Industriel », Continuité, no 96, printemps 2003, pp.20-50.

Desjardins, Pauline, Le Vieux-Port de Montréal, Montréal, Éditions de l’Homme, 2007, 224 p.

« Histoire », Quais du Vieux-Port de Montréal, [En ligne], http://www.quaisduvieuxport.com/fr/histoire

Le port de Montréal, documentaire de Gilles Blais, Québec, Office National du film du Canada, 1975. [En ligne] http://onf-nfb.gc.ca/fra/collection/film/?id=4823

« Le port au fil de son histoire », Port de Montréal, [En ligne], http://www.port-montreal.com/site/1_0/1_7.jsp?lang=fr

« Secteur du port, Le patrimoine du Vieux-Montréal en détail », Ville de Montréal, [En ligne], http://www.vieux.montreal.qc.ca/inventaire/fiches/secteur.php?sec=h

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

La marina du Vieux-Po

La marina du Vieux-Po

rt -

La Tour de l'Horloge

La Tour de l'Horloge

-

Le Daniel McAllister

Le Daniel McAllister

au Vieux-Port d... -

Spectacle lors du mar

Spectacle lors du mar

ché public de P...

Hyperliens

- « Secteur du port, Le patrimoine du Vieux-Montréal en détail », Ville de Montréal

- « A trip through time », port of Montreal

- Le port de Montréal, documentaire de Gilles Blais, Québec, Office National du film du Canada, 1975.

- History of the Quays of the Old Port of Montréal

- Vue du port de Montréal, exposition virtuelle «Deux quotidiens se rencontrent», Musée McCord