Félix Leclerc, Québec’s pioneering singer-songwriter

par Gaulin, André

Félix Leclerc, already a highly-acclaimed author in the early 1940s, and well-known in particular for his trilogy, Adagio, Allegro and Andante, did not initially see himself as a singer-songwriter or chansonnier. The reason was simple: the French Canadian literary establishment saw no inherent value in the poetic character of Leclerc’s few early musical texts. For the literary pundits of the time, such songs could at best be considered in the same category as French music hall ditties, a genre they considered frivolous, or else folk music, which they looked down on. It was the response in France to Félix Leclerc’s songwriting and performing style that transformed perceptions of his “poetry given voice”. Leclerc was a pioneer who opened the way for the concept of “songs with content”, and in fact gave legitimacy to this way of singing which would become so popular in France, in Québec and all across French Canada.

Article disponible en français : Félix Leclerc, père de la chanson québécoise

Songwriting was not considered literature in 1950s Québec

The young and accomplished poet Sylvain Garneau provided an eloquent illustration of the low regard in which songs and songwriting were held when, in a personal letter written in the fall of 1952 (NOTE 1), he recounted knowing Félix, having helped him plant potatoes in his vegetable garden in Vaudreuil and having listened to him singing his “petites chansons” all night long, although, as Garneau added with revealing condescension, “We’d never for a moment have imagined that he would gain success with that!”. The “that” in question was songwriting and, in particular, those “petites chansons” that were generating so much acclaim. This was also a period when influential members of the clergy, who often played the role of literary critics in Québec society, were expressing strong opposition to “French songs”, which they judged on the whole to be evil and depraved. There was even a popular movement in Québec under the influence of the Reverend Charles-Émile Gadbois around the idea of “Proper Songs”. It developed into a whole publishing industry that brought out 500 “Proper Songs” between 1938 and 1951, many of them expurgated versions of the originals, taken from the folk and traditional repertoires of France and French Canada (NOTE 2).

What we now understand in retrospect is that Félix Leclerc launched a song style or genre of which he himself was almost unconscious, his one driving ambition at the start of his professional life having been to become a novelist and playwright (NOTE 3), not an artist giving voice to poetry (NOTE 4). In point of fact, it was through acclaim in France that Félix came to see himself as the singer-songwriter – the chansonnier – he truly was. Only then did the artist begin to earn his living by singing – to suddenly discover, from the recognition he received from others, that he was in fact a poet. It has often been said that post-war France revealed this poet of song to a Québec that would otherwise have ignored him, but in reality, it was to the poetry-in-song genre that the French gave the fullest measure of admiration. In December 1951, still feeling somewhat apprehensive about the outcome of this adventure he was embarking upon, Félix travelled to Paris with the French impresario Jacques Canetti, taking a collection of thirty or so songs in his bags. He returned to Québec a year later, the winner of the prestigious Charles-Cros prize, representing a new genre he was to pioneer in Québec and of which he had been one of the foremost creators in France. Félix Leclerc and his poetic content-based songs rapidly became a cultural icon in Québec.

His song repertoire before his time in France

It is easier now to understand why Félix Leclerc only slowly adopted the song genre. Between his first song, “Notre sentier” (Our Trail), composed in 1934 (NOTE 5), and 1943, he is believed to have written only four songs (NOTE 6). Then, between 1944 and 1950, he added 28 more to his repertoire. In 1946 alone, he composed another nine songs, that being the most prolific songwriting year of his lifetime output of 138 compositions (NOTE 7). Yet Leclerc was still determined at heart to be a playwright. Even the songs he wrote before his departure for France were designed primarily to fill time between the scene changes of his play “Le p’tit bonheur” (A Small Delight), performed in 1948 (NOTE 8). The play comprises a series of six sketches and an equal number of songs, including “Le p’tit bonheur” (A Small Delight), “Notre sentier” (Our Trail) and “Le train du nord” (The Northbound Train). Analysis (NOTE 9) of the critical reception given to the Montréal performances of the play (NOTE 10) reveals that the songs provoked more interest than the play itself. Luce Jean commented in La Presse newspaper that “… the songs come across better than the actual play”, while Jean Vincent from le Devoir newspaper felt that “… while Leclerc is neither Ulmer, nor Trenet, nor Montand […] he has created the kind of new musical genre French Canada so desperately needs”. These two critical endorsements from April 21 were preceded by an article by Jacques Giraldeau in Notre Temps newspaper who wrote that he wanted to “pay tribute to our own very first chansonnier”.

The status of song in Québec

Drawing on our analysis of the newspapers and accounts of the period, we would argue that, although Félix Leclerc’s time in France unquestionably contributed to enhancing the image of song as a form of “poetry given voice”, it would be a gross exaggeration to claim that Québec was previously unaware of Félix, the singer-songwriter or chansonnier. It would perhaps be more accurate to say that many of the critics of the period were hoping to find in Leclerc a longed-for “saviour” and “modernizer” of Québec literature (NOTE 11). They did not, however, consider song to be legitimate literature and expressed no interest in Leclerc’s poetry-in-song. Taken together, Félix’s unique talent for song, the opinions of a few perceptive contemporary observers and, above all, the acclamation he received in France are what led to song gaining artistic and literary status in Québec.

En route for France

Félix Leclerc ended up performing an impressive 14-month run in 1951 and 1952 at the Trois Baudets Theatre in Paris, singing 32 pieces from his poetry-in-song repertoire (NOTE 12). The artist presented his program very simply, performing with only his guitar, a small footstool, his whistling skills, and wearing his traditional plaid shirt. For the French, he embodied their idea of “the man from the rustic log cabin in Canada” (NOTE 13). The simplicity and fresh, direct nature of his style captured their hearts. Leclerc, who had thought he was leaving for only a weekend or so, was a sensation in Paris. Jacques Canetti had signed up the artist after hearing “Le train du nord” (The Northbound Train) which local radio host Jacques Normand had felt he should hear. The French impresario’s nose for talent has long been recognized, but little credit has been given to the role played by Normand who, as of 1957, became the host of the Faisan doré (The Golden Pheasant), a cabaret where Franco-Québécois singers and songwriting were given pride of place.

What exactly was Félix singing that so captivated the residents of post-war France? Did their long-damaged hearts resonate with a kind of sadness when they heard songs about a man of no fixed abode, like “Bozo”, or about the pain of love, like the all-time favourite, “Le p’tit bonheur” (A Small Delight)? Did Parisians fall under the spell of the freshness of the poetry of “le Bal” (The Dance) where he “steals the sun so that day never comes”? Were they mystified by the surreal telling of “Le train du Nord” (The Northbound Train)? Were they enchanted by “Francis”, in search of a scented springtime, or taken aback by a song like “Petit Pierre” telling of his despair at the world and his choice of suicide? Did they want to leave for other parts with “the gulls and the tide” like “La fille de l’île” (The Girl on the Island) or did they, too, dream of giving up altogether on monarchy, along with Le roi heureux”? Were there dreams they also shared of finding the simple beauty of “Moi, mes souliers” (These Shoes of Mine)? Maybe. An observer from that period might perhaps explain that it was Félix’s quintessential on-stage persona that stunned audiences with its absence of a “civilized veneer”, its rustic audacity, the richness of his poetry… not to mention the handsome features of the poet with the voice that could sweep any woman off her feet! The poignant simplicity of his stage presence – a choice that later influenced Brassens – together with the poetry conveyed by words which are invitations to dreaming are better explanations for the reception that France afforded the poet from Québec than believing it was due simply to the somewhat melancholy tone of his pre-1952 texts.

The Profession of Singer-Songwriter: 1950-1970

So it was the French whose accolades made Félix Leclerc the singer-songwriter he became. For his part, he was too busy singing to create any new songs in 1951 and he wrote only one in 1952. Although his homeland was now ready to recognize his talent, paying tribute to him for the first time during his brief return to Montréal in April 1951 and then again in 1953, his singing career was centred primarily in Europe. He began by singing in Paris, with Jacques Canetti as his agent. After Jean Dufour became his agent for France in 1965, he also travelled around to different parts of the country to perform with his very spartan decors, most often in the Maisons de la culture (Cultural Centres). Félix Leclerc had signed with Polydor in 1950 for five years and sold his royalties to raise the money he needed to live. During this same period, Pierre Jobin was his agent for Québec and Félix also returned regularly to sing in his home country. However, it was his contact with Europe that opened his eyes to France as a country of new ideas, where religion was a far less predominant theme of discourse – and his poetry increasingly reflected these influences as the years went by. He abandoned the “canadiennefrancitude” (French-Canadienness) (NOTE 14) of a song like “Présence”(Presence) from 1948, so melancholy and desperate in content but so hauntingly beautiful in its music, for songs with a more moralistic tone, (“Comme Abraham” (Like Abraham), 1954, “Attends-moi ti-gars” (Wait for Me, My Lad), 1955), for songs marked by humour (“Chanson du pharmacien” (The Pharmacist’s Song), 1954, “O mon maître” (Oh, Master Mine) , 1957), love songs (“Ce matin-là” (That Morning), 1955, “Litanies du petit homme ” (Little Man’s Prayers), 1958), songs celebrating his love for animals, like “ Blues pour Pinky” (Blues for Pinky), 1955, or “ Les Perdrix” (The Partridges), 1955), for songs comprising the “King Cycle” (“Le roi et le laboureur” (The King and the Plowman), 1956, “Le roi viendra demain” (Tomorrow the King Will Come), 1957), and songs evoking his Québec roots, such as the “Chanson des colons” (Song of the Settlers), 1957, “La Drave” (The Log Drive), 1954, and especially “Tu te lèveras tôt” (Get Yourself up Early), from 1958. In this period before 1960, Félix added 30 more songs to a repertoire which now numbered 62 in all.

The 44 songs that followed were written during the “Quiet Revolution” that transformed Québec society between 1960 and 1970. Although he did not entirely abandon the sweetly poetic themes he drew from daily life, or the poetry-in-song inspired by his keen observations of the world around him, the pieces Leclerc wrote during this momentous decade reveal a man struggling with a crisis in values. His songs show a man plagued by doubt and a degree of rebellion, a man who expresses stronger feelings of attachment to human values and to life (NOTE 15). The songs from this period reflect both the personal – he had found a new life partner – and social influences he was undergoing, as he maintained close ties with Québec society during this time of major upheaval.

Strangely enough, the words of those songs written for performances throughout France – often scheduled for only part of the year – had in many ways more appeal for a Québec public that recognized itself and its references in them, whereas the French remained fundamentally more deeply attached to Félix’s post-war poetry. Of course, some of his compositions still reflected his earlier style, like “Passage de l’outarde” (Wild Geese Fly Overhead), 1967, or the brilliant “Variations sur le verbe donner” (Variations on the Verb: To Give), 1967. All the same, Québeckers recognized themselves more fully in his rich creative output of 1969 where his “Grand-papa Panpan” defeats fear, when he calls for a new generation of ideas (“J’inviterai l’enfance” (I Will Call Out to Other Children), or when the poet narrates the dispossession in “Richesses” (Wealth). This Félix had again become the father of two children, had moved back to the Île d’Orléans of his forefathers and longed for a more settled life (NOTE 16). However, a milestone event was about to occur, one that would have a major influence on the 32 songs he wrote after 1970.

Poet, Show Me Your Papers!

While Félix Leclerc was spending most of his time and making his living in France, Québec society was changing. The artist had not taken sides in the great Québec vs. Canada debate. But an incident occurred, and became his “road to Damascus moment”. As he arrived back at the Île d’Orléans, a soldier from the Canadian army occupying “the province of Québec” under the provisions of the War Measures Act adopted in October 1970 ordered him to show his papers. Not only was he confronted with the stark reality of the occupation of his homeland, he was also overcome, in spite of himself, by a wave of indignation that exploded in his “L’Alouette en colère” (Lark in a Rage), 1972), a song drawn as tight as a bowstring, almost longer to read than to sing!

So there you have Félix, now an ardent champion in his unique way for “a country called Québec”, the forces at his command being its rivers, and his defence staff, the wind: “Chant d’un patriote” (Song of a Patriot). He still remained a poet: “Comme une bête” (Like an Animal), so understated in tone and so powerful in expression, and humour also continued to be part of his creative style: “Les Poteaux” (Poles). This man with a strong social conscience: “Les 100 000 façons de tuer un homme” (100,000 Ways to Kill a Man) was also sensitive and loving: “Sors-moi donc, Albert” (Take me out, Albert) and the Félix (as everyone affectionately called him) of the songs from 1975 on was at one with his compatriots. Those same compatriots had in fact travelled earlier than him along the road to a political reading of Québec society in their understanding of the symbolism of his 1948 evocation of rural Québec, “Hymne au printemps” (Ode to Spring) where the “Frogs” sing for freedom.

His last album, recorded in 1978 and entitled “Mon fils” (My Son) like the song of the same name included on it, was a celebration of the strong nationalistic sentiments of an entire nation, with compositions such as “La nuit du 15 novembre” (The night of November 15) and “L’An 1” (Year 1). Leclerc returned to France for a final tour to pay tribute to the 25 years of his European career (“Merci, la France”, 1976 (Thank you, France), a two-record set), but after that the grand old man only rarely left his home environment, remaining almost entirely on his island. If the man himself was a loner, so was the singing poet (NOTE 17). The path of his life could well be seen to have reflected that of many Québeckers. “Born into an inherited sadness” and “French-Canadianness” and bravely choosing to “make a commitment to hope”, as he so movingly showed in his “Prière bohémienne” from 1955, quoted by his friend Pierre Devos during the ceremonies following the death of the poet in 1988), Leclerc moved from the “trail” of 1934, obstructed and “torn by the plow” to the royal way provided by the liberating presence of the great Saint Lawrence River, the wellspring from which the lofty symbolism of his evocative “Le tour de l’île” (Travelling Round the Island), 1975 (NOTE 18), sprang. His entire musical repertoire was a reflection of the artist’s metamorphosis from this “inherited sadness” (Gaston Miron) to an emancipation of his own choice, shaped predominantly by two influences: the time he spent in France and the Quiet Revolution (NOTE 19) in Québec.

The Québec public identified strongly with Leclerc’s musical repertoire. His last major concert, “Le loup, le renard et le lion” (The Wolf, the Fox and the Lion), where he performed for the Superfrancofête in August 1974, along with Gilles Vigneault and Robert Charlebois, drew a crowd of 200,000 people to the Plains of Abraham in Québec City. The entire Francophone community wanted to pay homage to his talent and representation of what was best in Québec. Leclerc had made a real exception in leaving his refuge on the Island. He could well have said to the crowd whose hearts he ruled, as he had sung in “La mort de l’ours” (Death of a Bear), “Good day, Sire, It is I, the wolf, Do you see me, do you hear me? I have journeyed through the woods, To pay you due homage”.

Québec’s pioneering singer-songwriter

Through his successes in France where he had gained widespread acclaim, Félix Leclerc discovered that he was both a poet and a chansonnier, and it was through him that the Québec poetry-in-song genre came into existence (NOTE 20). This song style, initially called French-Canadian, evolved in particular as a result of influences of the 1950s. One telling example was the song-writing competition, Festival Radio-Canada, launched in April 1956, and which attracted hundreds and hundreds of entries. Almost 1,200 unpublished songs were submitted under pseudonyms; 120 of them were selected after a first round of evaluations. For the competition final, an international jury panel chose 12 of the 31 songs that had successfully passed the second level of selection and awarded six honourable mentions, one radio prize, one television prize, one prize identified as the “Amicale de la chanson” (Fellowship of Song Award) and three first prizes. The songs that received these top honours were released together in a boxed set entitled “Douze chansons canadiennes” (Twelve Canadian Songs) which also included accolades from the Canadian Prime Minister, Louis Saint-Laurent, and the Québec Premier, Maurice Duplessis. The (bilingual) text of the booklet accompanying the set was written by the poet, Éloi de Grandmont, whom Lionel Daunais (one of the prizewinners) had already set to music. The tone to be used by future chansonniers was now set; it ranged from the humorous (“Les perceurs de coffres-forts” (The Safecrackers) and “Voyage de noces” (Honeymoon), both by Daunais) to the popular (“Sur l’perron” (Out on the Porch), winner of the 2nd prize), while the “Grand Prize of (French) Canadian Song” went to the poetic “Le ciel se marie avec la mer” (The Sky Weds the Sea) by Jacques Blanchet, who, like Daunais, was also a two-time prizewinner.

The number of chansonniers increased exponentially at the end of this decade – and the public was eager for any opportunity to experience and applaud their talents. In 1958, some of these singer-poets, driven by a common quest for quality in both words and music, formed a group they called “Les Bozos”, a clear tribute to Félix Leclerc. The group was composed of Jacques Blanchet, Hervé Brousseau, Clémence DesRochers, Claude Léveillée, Raymond Lévesque, Jean-Pierre Ferland and André Gagnon. Chez Bozo was also the name of the venue where they performed. In the year that followed, performances by Jean-Pierre Ferland in Montréal and by Gilles Vigneault in Québec City in their turn became real successes. The sixties saw the advent of Québec’s Boîtes à chanson (song cabarets). Wherever their inspiration was drawn from – Montréal or Québec City, the village of Percé or the region north of Montréal – aspiring young singer-songwriters found in the Boîtes à chanson opportunities to sing their own compositions, usually on the theme of love, to receptive audiences all around the province. While many of them stayed only a short while in the public eye, these singers – people like Tex Lecor, Hervé Brousseau, Pierre Calvé, Pierre Létourneau, Jean-Paul Filion, Christine Charbonneau or Marie Savard – did have an impact on the chansonnier poetry-in-song genre; others, singers such as Claude Dubois, Claude Gauthier, Georges Dor, Claude Léveillée, Monique Miville-Deschênes and of course Gilles Vigneault and Jean-Pierre Ferland remained popular for years. Women – the best examples being Monique Leyrac and Pauline Julien – were better known for their interpretations of other people’s compositions, although Pauline Julien also wrote the words of some beautiful pieces herself.

The genesis of this new genre was due largely to the pivotal influence of Félix Leclerc, since it had been through his unique creative style and pioneering of the profession of singer-songwriter that all the recent generation of chansonniers and performers had learned about poetry-in-song. From then on, the Québec chanson was recognized as existing in its own right.

André Gaulin

Professor Emeritus (Arts and Letters)

Université Laval

Notes

1. Garneau, Sylvain, “Lettre à Marie”p. 141-145, Objets retrouvés : poèmes et proses, Montréal, Librairie Déom, 1965, 331 p.

2. See the article “La bonne chanson, recueils de l’abbé Charles-Émile Gadbois” by Georges Gauthier-Larouche in Lemire, Maurice (Dir.), Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec,Vol. 2. Montréal, Fides, 1980, 1363 p.

3. Adagio, Allegro, Andante, respectively collections of short stories, fables, poems and tales in prose were published by Fides in 1943 (in the first case) and 1944 (for the latter two) and were printed in several editions. Professor Aurélien Boivin describes them as best-sellers of the period. See Lemire, Maurice (Dir.), Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec,Vol. 3. Montréal, Fides, 1982,1252 p.

4. The expression “poésie orale sonorisée” (poetry given voice) given to the sung word comes from the mediaevalist Paul Zumthor.

5. In the first version of Rêves à vendre ou le Troisième calepin du même flâneur (Dreams for Sale or the Third Notebook of the Same Idler), (1984), Félix stated that he owed his first song to his English teacher in Québec, Mr. Ormsby. He wrote in this document what he recounted almost word for word to Jean-Pierre Ferland in an interview he later gave at his home in Saint-Pierre, Île d’Orléans, in January 1985: “I was 19. (Mr. Ormsby) was scandalized to discover that I cared only for religion, that all I wanted in life was to go to Heaven and that I was close to wanting only to die. My contempt for anything of this world so upset him that it made him hate all those who had weighed me down with such chains”. Felix described going one evening to a children’s concert at the Anglican church on Saint Joachim Street in London and seeing, two pews in front of him, this same Englishman “with tears streaming down his face”. Félix suddenly realized that he did not have even one single love song for his homeland, went out the next day and bought a guitar (he wrote that he would end up going through eight of them) and added: “I listened to my heart teaching me how to be delivered of a first song”. It was “Notre sentier” (Our Trail).

6. The fourth was “le Québecquois”, a song that remains little known, in spite of its importance for an understanding of Leclerc’s work. He expressed the idea in that song that French Canadian performing artists do not see their world as a subject for literature. Did Félix, whom his father had once told to observe his fellow Québeckers and describe what he saw, in fact believe it was? Maybe he did, because he added another 28 songs to his repertoire over the course of the next seven years, between1944 and 1950.

7. The words of the poet’s songs can be found in Leclerc, Félix, Cent chansons, Montréal, Fides, 1970, 255 p. For an overview of his complete works, with an introduction, a chronology of his life and work and a discography, see Leclerc, Félix, Tout Félix en chansons, Québec, published by Nuit blanche, 1996, 285 p. To the songs Félix himself wrote should be added another 11 written by other songwriters, including Jean-Pierre Ferland, Michel Rivard and Maurice Fanon, whose songs he interpreted, or by authors whose works he set to music, like Arthur Rimbaud, Francis of Assisi. Many of Félix Leclerc’s versions of the songs he sang are available through the Internet, notably “Le p’tit bonheur” (A Small Delight), “Le train du nord” (The Northbound Train), “Le tour de l’île” (Travelling Round the Island), “La mort de l’ours” (Death of a Bear), “Moi, mes souliers” (These Shoes of Mine), “L’Alouette en colère” (Lark in a Rage), “Attends-moi ti-gars” (Wait for Me, My Lad), etc.

8. In 1948, the play was performed in Vaudreuil, Rigaud and Saint-Jérôme, then in Montréal in April 1949 (three nights at the Théâtre des Compagnons).

9. A research grant received from the SHRC (around 1989) by Professors Roger Chamberland and André Gaulin enabled them to carry out a study of how newspaper articles referred to Leclerc before he left for France in December 1950. An unpublished report by researcher Gilles Perron, who teaches today at the Cégep de Limoilou, also found that when Leclerc had his play, “Le p’tit bonheur” (…), performed in Paris in 1964, with the help of a $15,000 grant from Québec’s Ministère des Affaires culturelles, the critical reaction was somewhat negative, although there was considerable praise for the songs performed between the sketches and for the short recital that closed the evening.

10. “La p’tite misère” (Tough Times), another Leclerc play made up of a series of six sketches and the same number of songs was staged in April 1950, although this time critical reviews did not comment on the songs.

11. This clash of views between the author and literary critics of the time was made particularly evident with the publication of Dialogues d’hommes et de bêtes (Dialogues of Men and Animals) in Spring 1949.

12. Prior to this, he had performed for four weeks, as of December 20, 1950, at the ABC, another small Parisian music hall.

13. English equivalent of words from a song by Mireille Brocey/Loulou Gasté, 1948, made popular by Line Renaud.

14. “French-Canadianness” is an approximation of the term “canadiennefrancitude”, a literary concept the author of this article coined to characterize a certain type of literature current in Québec between 1940 and 1960, where the idea of failure is dominant and the underlying premise is “the belief that happiness is reserved for others”. The reader can find a number of entries the present author also wrote on this question, in Volume 3 of the Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec.

15. Examples would be the poetic themes based on everyday experiences found in songs such as “Je cherche un abri pour l’hiver” (I’m Looking for Winter Shelter), 1960, “Sur la corde à linge” (Out on the Clothesline), so simple in its expression, 1963, or “Tzigane” (Gypsy), 1966, marked by a strong bohemian influence); poetry in song, inspired by a sensitive observation of life, in “Premier amour” (First Love) or “Douleur” (Pain), 1963; a man plagued by doubt in “Mes longs voyages” (My Long Journeys), 1965, a song that exploits a variety of melodic themes; a man driven by a kind of revolt in “Dieu qui dort” (God is Sleeping), 1965; his attachment to human values in “La vie, l’amour, la mort” (Life, Love and Death), 1962, and his attachment to life in “Le jour qui s’appelle aujourd’hui” (The Day that is Today), 1964.

16. Even so, he continued to give many concerts in Québec, including a 9-evening series of performances at Salle Maisonneuve at Montréal’s Place des Arts in 1967.

17. His nationalism and love for René Lévesque led him to take the stage during the 1980 Québec referendum. Moreover, it was even he, the poet, Félix Leclerc, who was waiting in the wings of the Paul-Sauvé Arena in Montréal on the evening of May 20, 1980 because he was the person slated to announce the victory for the yes side…

18. This song, with its strong evocation of longed-for independence, also conveys how tired he is of what history has reserved for Québec– “le difficile et l’inutile” (the difficult and the useless) – but enables him to find new energy through the landscape and in parallels with France: “C’est-y en France? ° C’est comme en France ° Le tour de l’Île” (Is it in France? ° It’s like in France ° Travelling Round the Island).

19. A series of twelve radio broadcasts prepared on the topic by the author of this article for Radio Galilée in Summer 2003 was rebroadcast at the request of the station in Summer 2010.

20. This song style was one that others had contributed to before him: La Bolduc, Lionel Daunais (who experimented with a range of styles, simply to make ends meet), Oscar Thiffault (whom Trenet could quote by heart), and Raymond Lévesque (who also sang in the cabarets of the Rive gauche in Paris). A lot of others should also be mentioned here: one example here is Guy Maufette, host of a number of radio and television song programs, who presented Félix, singing “Le Bal” (The Dance), for the very first time on television on the program called “Carrousel” on November 30 in 1953. Other notable influences were Jacques Normand, the host of “Nuits de Montréal” (Montréal Nights), as well as “Le Saint-Germain-des-prés” (the Saint-Germain-des-Prés) and later “Le Faisan doré” (The Golden Pheasant), and Fernand Robidoux, remarkable for the prominence he gave to this song style in French on radio stations that included CHLT (Sherbrooke), CHLN (Trois-Rivières), CKVL (Verdun and CKAC (Montréal). It was also Robidoux who translated the well-known American song “Promises” into “Je croyais” (I Used to Believe). Above all, it is most important to recognize that the development of the text-based song style was a complex and pluralistic phenomenon.

Bibliography

Bérimont, Luc, Félix Leclerc : choix de textes et de chansons, Paris, Seghers; Montréal, Fides, 1964, 186 p.

Bertin, Jacques, Félix Leclerc, le roi heureux : biographie, Paris, Arléa, 1987, 315 p.

Chamberland, Roger, et André Gaulin, La chanson québécoise : de la Bolduc à aujourd’hui, Québec, Nuit blanche éditeur, 1995, 593 p.

Gaulin, André, « Cent chansons, recueil de Félix Leclerc », dans Maurice Lemire (dir.), Dictionnaire des œuvres littéraires du Québec, t. V : 1970-1975, Montréal, Fides, 1987, p. 105-110.

Leclerc, Félix, Cent chansons, Montréal, Fides, 1970, 255 p.

Leclerc, Félix, Tout Félix en chansons, établissement du texte, Roger Chamberland; introduction, André Gaulin; chronologie, discographie, bibliographie, Aurélien Boivin, Québec, Nuit blanche éditeur, 1996, 285 p.

L’Herbier, Benoît, La chanson québécoise : des origines à nos jours, Montréal, Éditions de l’Homme, 1974, 190 p.

Sermonte, Jean-Paul, Félix Leclerc, roi, poète et chanteur, Monaco, Éditions du Rocher, 1989, 155 p.

Audiovisual documents

Heureux qui comme Félix : une histoire de Félix Leclerc. Les grands moments de sa vie et de sa carrière; témoignages et chansons, série radiophonique réalisée par Jacques Bouchard, entrevues et narration de Monique Giroux, Montréal, Société Radio-Canada et GSI Musique, 2000, 10 CD.

« C’est la première fois que j’la chante » [en ligne], documentaire de Mazouz, textes de Marcel Dubé, narration de Monique Leyrac, Montréal, Office national du film du Canada, 1988, http://www.onf.ca/film/cest_la_premiere_fois_que_jla_chante.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

À l'occasion de la Su

À l'occasion de la Su

perfrancofête e... -

Affiche annonçant la

Affiche annonçant la

programmation «... -

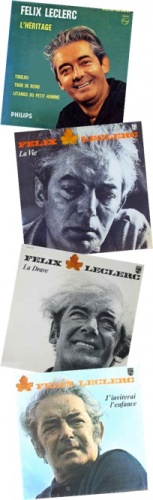

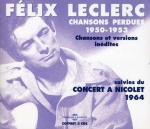

Coffret CD Félix Lecl

Coffret CD Félix Lecl

erc – Chansons ... -

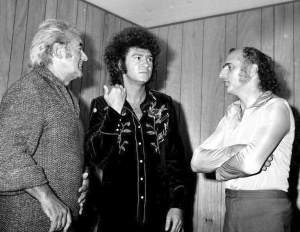

Félix Leclerc en comp

Félix Leclerc en comp

agnie de George...

-

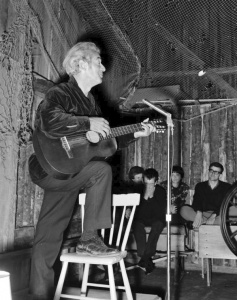

Félix Leclerc en pres

Félix Leclerc en pres

tation à Saint-... -

Félix Leclerc en pres

Félix Leclerc en pres

tation à Saint-... -

Félix Leclerc et les

Félix Leclerc et les

membres du gro... -

Félix Leclerc lors d

Félix Leclerc lors d

e son passage a...

-

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i...

-

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i...

-

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

Félix Leclerc, auteu

Félix Leclerc, auteu

r-compositeur-i... -

-

Les compagnons de Sai

Les compagnons de Sai

nt-Laurent en 1... -

Matrice vinyl des dé

Matrice vinyl des dé

buts de Félix L... -

Poète-chansonnier Fe

Poète-chansonnier Fe

́lix Leclerc, d... -

Texte manuscrit de Fé

Texte manuscrit de Fé

lix Leclerc pou...

Documents sonores

-

Extrait de la chanson « Contumace », interprétée par Félix Leclerc

Extrait de la chanson « Contumace », interprétée par Félix Leclerc

-

Extrait de la chanson « Le tour de l'île », interprétée par Félix Leclerc

Extrait de la chanson « Le tour de l'île », interprétée par Félix Leclerc

-

Quand les hommes vivront d'amour (J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lion, 1975)

Quand les hommes vivront d'amour (J’ai vu le loup, le renard, le lion, 1975)