Old Prison of Trois-Rivières

par Harvey, Christian

Located in downtown Trois-Rivières, the Old Prison opened in 1822 and was one of only a handful of historic buildings to survive the great fire of 1908. The prison’s age, architectural and historical significance, renowned architect, and long service in its original function all influenced the Quebec government’s 1978 decision to name the building a historic monument. The Old Prison is at once the architectural embodiment of a period of innovation in prison design that swept over Quebec in the early 19th century and a monument to the hardships of prison life experienced by generations of inmates between 1822 and 1986. Today visitors to the prison, now part of Musée québécois de culture populaire, can enjoy a one-of-a-kind experience known as “Go to jail!” which puts them in contact with former prisoners willing to share their experiences.

Article disponible en français : Vieille prison de Trois-Rivières

Prisons and Politics

In 1799, the Legislative Assembly of Lower Canada enacted the first ordinance to build prisons in the province’s various districts. A committee was formed to carry out the project, and heated discussion ensued in political circles as to how to fund these institutions. Finally, the Assembly adopted the Act to provide for the erecting of a Common Gaol in each of the Districts of Quebec and Montreal respectively, and the means for defraying the expenses thereof. Prisons opened in Quebec City in 1809 (today the Morrin Centre) and on Montreal’s Champ-de-Mars in 1811 (now vanished). A similar law was enacted for Trois-Rivières in 1811, though it took five years for builders to break ground.

François Baillairgé and Quebec Prison Architecture

In 1815 François Baillairgé (1759–1830) was commissioned to produce drawings and specifications for the Trois-Rivières prison. Baillairgé was a well-known architect who had trained as a sculptor, carpenter and architect with his father Jean Baillairgé and then studied in Paris at the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture. Well known for his work on the Quebec City court house (1799) and prison (1807), he seemed just the man to design a new prison for Trois-Rivières using the most modern architectural approaches.

Baillairgé drew on the ideas of British prison reformer and theorist John Howard who advocated choosing a suitable location and providing inmates with satisfactory living conditions, including adequate ventilation and heating. He believed in segregating prisoners by age, sex and the nature of their crime. Another influence was the aestheticism in the work of British architect James Gibbs (NOTE 1). Trois-Rivières Prison is thus influenced by English Palladian architecture with its formal balance, harmonious proportions and monumental rhythm.

The new building was 28 meters long by 11 meters wide, and divided into three sections. The central section contained the front desk, offices, chapel, kitchen and dining hall. The two other wings were given over to the cell blocks, except for the second floor of the west wing which housed the prison warden and his family. Isolation cells for solitary confinement were located, naturally, in the basement (NOTE 2).

Construction dragged on from 1816 to 1822, with a temporary interruption in March 1819 due to a lack of funds. Despite the commissioner’s conclusion that the prison was ready to accept prisoners early, it did not begin to operate until the funds to complete it became available in 1822.

Guarding, Punishing, Rehabilitating

The rise of the modern prison is well documented today (NOTE 3). But 18th- and 19th-century Quebec and France had no such institutions, in our modern sense of the term. Criminal punishments were primarily chosen for their impact on the public imagination. Depending on a crime’s severity, its perpetrator could be condemned to a fine, a public apology, corporal punishment like flogging, the stocks or the pillory, or even death (NOTE 4). In this conception of crime and punishment, a prison’s only logical role was to provide a temporary home to prisoners awaiting sentencing.

Things began to change in the late18th century when reformers, especially in Britain, started criticizing the barbarity of public punishment, thus laying the groundwork for the modern prison model. As society underwent the fundamental shift to free-market capitalism, petty crime ran rampant and prisons became places for enforcing social norms by punishing disorderly conduct such as vagrancy, drunkenness, desertion, theft, and offences to public morals and public order (NOTE 5). Imprisonment became a punishment unto itself as well as a means to rehabilitate prisoners and protect the general public, although corporal punishment was still practiced. Such was the historical background when Trois-Rivières prison opened its doors.

Sentences, Hangings and Time “In the Hole”

The old Trois-Rivières prison housed inmates for 164 years, from 1822 to 1986, making it the longest serving correctional institution in Canada. Seven inmates were hanged on the premises over this period for serious crimes such as murder (the last in 1934). Yet most of the 19th-century sentences meted out were for minor crimes punished by short jail terms—less than 15 days in 78% of cases (NOTE 6). Trois Rivières’ “specialization” in minor sentences was gradually formalized over the next century as hardened criminals were sent to other institutions, notably Orsainville in the Quebec City area. The vast majority of sentences were served by “doing one’s time”: the tough and monotonous (albeit in this case relatively brief) experience of daily life in a prison that was never outfitted with a workshop.

In the 19th century corporal punishment like flogging was a common method for “breaking” uncooperative prisoners. But an even more common way for prison authorities to assert their control was a stint in “the hole.” Prisoners in isolation cells were chained like their medieval counterparts to prevent them from digging escape tunnels. Isolation cells were used into the mid-seventies, and remain a painful memory for many prisoners.

From Prison to Museum

As the decades passed, the age of the Trois-Rivières correctional institution increasingly raised questions about whether the facility was up-to-date and prisoners’ conditions acceptable. As early as 1905 the prison’s age was the butt of jokes: it was ironically referred to as the only historic monument of its kind in Quebec (NOTE 7). There were complaints about foul-smelling toilets, inadequate heating in winter, and fleas and cockroaches. Some improvements were made over the years, but to little effect. Finally, after several election promises, the prison closed its doors in 1986.

The prison’s old age, long years of service, heritage and architectural value and famous designer, François Baillargé, make it a unique monument (NOTE 8). In 1978 its heritage value was recognized when Quebec’s culture ministry named the building a historic monument. When the prison closed in 1986, guided tours were organized to show the facility to the general public. A plan to preserve and develop the Old Prison was subsequently made part of plans for a new city museum.

Initially led by Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, the museum project was originally intended to house Robert-Lionel Séguin’s monumental collection of 35,000 ethnographic artefacts, acquired by the museum in 1983, along with an archeological collection of some 30,000 prehistoric and aboriginal artefacts. After much political wrangling construction finally began in 1993. A new museum building would house the Musée des arts et traditions populaires du Québec while the old prison was renovated and brought up to code. The second floor was converted into office space. The museum finally opened on June 26, 1996. It followed in the footsteps of Quebec City’s former prison which was incorporated into Musée national des Beaux-Arts du Québec in 1990 to add exhibition space. But only the Trois-Rivières museum has developed an original visitor “experience” which draws on and shares the lived experience of prisoners within the prison walls.

Musée Québécois de Culture Populaire Gives the Prison a New Lease on Life

After significant financial setbacks, Musée des arts et traditions populaires changed vocations to become Musée québécois de culture populaire, housed in the same space. Management looked closely at renovations made to the Old Prison, which in many ways ran contrary to the institution’s spirit. To address this situation, a second restoration was planned with renovations based on photographs taken during the 1970s historic building designation process.

A new concept was developed to breathe new life into the Prison: the “Go to Jail” visitor experience. This hour-and-fifteen-minute guided tour, often led by former inmates, shows visitors through prison cells and the “hole” as they learn about the hardships of prison life. The museum’s “Sentenced to One Night” program is open to groups of 15–39 who quite literally spend the night in exchange for a “fine” of $60; the traditional prison breakfast of oatmeal and toast is included. Another program, “Verdict Attendu” (available in French only) was introduced in 2011. It offers visitors the chance to be jury members in a reconstruction of a 1920s trial.

By restoring the Old Prison of Trois-Rivières to its original appearance in a way that respects its singular history, the museum has accomplished two valuable objectives: showcasing the remarkable built heritage of this historic monument and bringing the site’s rich intangible heritage to life.

Christian Harvey

Centre de recherche sur l’histoire et le

patrimoine de Charlevoix

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

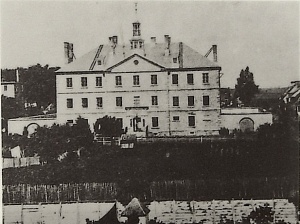

La façade de la priso

La façade de la priso

n de Trois-Rivi... -

La prison de Trois-Ri

La prison de Trois-Ri

vières en 1900 -

La prison de Trois-Ri

La prison de Trois-Ri

vières vers 188... -

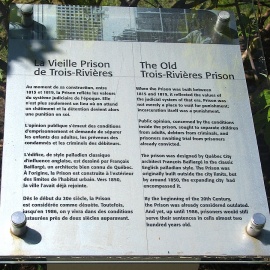

Panneau d'interprétat

Panneau d'interprétat

ion de la Vieil...

-

Trois-Rivières en 190

Trois-Rivières en 190

0: en haut à dr... -

Une des portes de la

Une des portes de la

Vieille prison ... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières

-

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières : c... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières : c... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières : l...

-

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières : p... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières, 20... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières: ac... -

Vieille prison de Tro

Vieille prison de Tro

is-Rivières: pe...

Catégories

Notes

1. Guy Godin, “La vieille prison de Trois-Rivières change de vie.” Continuité 69 (1996), p. 12–13.

2. Benoît Gauthier. “La vieille prison de Trois-Rivières.” Cap-aux-Diamants 98 (2009), p. 33.

3. In France, see Michel Foucault, Surveiller et punir : naissance de la prison. Paris : Gallimard, 1975. (English translation: Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Modern Prison. Trans. Alan Sheridan. New York: Vintage, 1995.) For Quebec, see Jean-Marie Fecteau, La liberté du pauvre : sur la régulation du crime et de la pauvreté au XIXe siècle québécois. Montréal, VLB, 2004.

8. See: http://www.historicplaces.ca/fr/rep-reg/place-lieu.aspx?id=4076