Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons: a little-known gem of “Ontario’s New France”

par Marchildon, Daniel

The historical site Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons located on the Wye River (originally named Isiaragui in the Huron language), which flows into Georgian Bay, proudly stands as a living testimony to one of the most dramatic chapters of the history of New France. The modern reconstruction of the twenty-two buildings surrounded by a palisade that bring to life the ten years of this fortified Jesuit mission’s existence (1639-1649) constitutes a strange paradox. The meeting of two of Canada’s founding peoples, the Wendat (or Huron) and the French, that resulted in tragic consequences, is commemorated in an area that is very anglophone, by an English-language organization, Huronia Historical Parks/Parcs historiques de la Huronie, which has a few francophone and bilingual staff members. Nevertheless, this historical site located in the heart of Ontario remains a gem of Canada’s French heritage stretching back to the country’s very beginning.

A long-lasting historical interpretation site

After 45 years, the present site of Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons has surpassed by many years the life of the original site that was only in operation for a decade. Of course this longevity has led to some problems. The cedar posts of the palisade have had to be replaced. That has also been the case for the roofs of the buildings, which originally were made of elm bark but have since been replaced with synthetic materials. It has also been necessary to update the interpretation programme. But Sainte-Marie has always remained a much-appreciated historical interpretation site. The number of annual visitors has stayed constant, at about 100,000, 20% of which are students (and a few celebrities like Pope John-Paul II, in 1984). The importance of Sainte-Marie as an educational resource has been recognized by the Ontario provincial government, which early in the decade starting in 2000, made the history of Sainte-Marie part of the Ontario school curriculum for Grades 3, 6, and 7, for English- as well as French-language schools.

Of course, since the official opening of Sainte-Marie in 1967, the perspective of specialists of the history of New France and of First Nations history regarding this period has evolved. The interpretation offered today at Sainte-Marie is therefore more balanced. It seeks to explain the grandeur and nobility of the events, but also the mutual incomprehension between the actors of the period, and the particularly tragic dimension of the story, mainly for the Wendats, since this mission nearly brought about the disappearance of the Huron nation. Even today, as notes Alan Gordon, professor of History at the University of Guelph: “ (…) Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons portrays a partnership between the Wendat and French missionaries, and ignores, or at least plays down, Jesuit efforts to undermine every aspect of Wendat culture.” (NOTE 1)

What is the heart of the matter? Let us see what visitors to Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons discover.

Sainte-Marie, a small New France village

Why was this fortified mission ever built in 1639 in an area so remote and far-flung from the heart of a still fragile and fledging New France, 1,200 km or 30 days by canoe and around 40 portages from Quebec City? The answer is simple: the quest for souls and furs. From the very outset of New France, the French are motivated by two goals, one being monetary— they seek to make a profit from the fur trade— and the other being spiritual— they hope to convert the Amerindians to the Catholic religion. Even though evangelization will be the primary function of the settlement, Sainte-Marie will serve both of these interests.

In 1610, a European visits for the first time the territory occupied by the Wendats (given the name Hurons by the French) on the shores of Georgian Bay, at approximately 160 km north of present-day Toronto. He is the young Étienne Brûlé, who will work as an interpreter among the Wendat. Five years later, Samuel de Champlain and the Recollet priest Joseph Le Caron come to Huronia, the former to solidify a military and commercial alliance with the Wendats, the latter to begin their conversion to Christianity. For the missionaries, the Wendats represent good candidates for conversion since, contrary to many of the other Native peoples, they are sedentary (NOTE 2).

In 1626, the Jesuit fathers take over from the Recollets. Jean de Brébeuf, one of New France’s most illustrious missionaries, takes up residence in Huronia. Brébeuf is named the superior of the Sainte-Marie mission to the Hurons in 1634, and will participate in founding the first European community to be established so far in the interior of the North American continent. By establishing Sainte-Marie, the goal of the French missionaries is to create a base for their operations in the Wendat territory where they will be able to meet and obtain supplies to then head back out to the twenty or so surrounding Wendat villages to continue preaching.

Father Jérôme Lalemant, who becomes the second superior of the mission in the land of the Hurons in 1638, describes the central location chosen in the Wendat territory, on the shore of a beautiful river, and the merits of his settlement plan:

“[...] And thus we have now in all the country but a single house which is to be firm and stable, — the vicinity of the waters being very advantageous to us for supplying the want, in these regions, of every other vehicle; and the lands being fairly good for the native corn, which we intend, as time goes on, to harvest for ourselves.” (NOTE 3)

Thus, in 1639, a dozen Frenchmen erect the first dwelling in the rudimentary “en piliers” or post style. Over the following decade, Sainte-Marie will become a virtual small village comprising 22 buildings, including a blacksmith’s shop, two churches, a refectory, a hospital, several workshops, cultivated fields, and a stable.

A part of the mission is reserved for Native converts, who have their own chapel, with only a dirt floor, in order to allow the okis, or spirits of the earth, to circulate freely, in accordance with Wendat beliefs. The personnel of the mission will reach a peak of 18 missionary priests, who are supported in their efforts by many lay people, lay brothers, donnés (a term derived from the French verb donner, to give, to designate this group of men that offer their services for free to the Jesuits), and even a few soldiers to ensure their protection. In fact, in 1648, there are a total of 66 Frenchmen at Sainte-Marie. In the context of the New France of this period, with its scant European population, this is quite a significant number (NOTE 4).

Missionaries and merchants hand in hand

If the religious mission is successful, it is in part because the commercial relations between the Wendat and the French continue expanding despite some major setbacks, as notes historian Bruce Trigger.

“[…] not only the total amount of trade with the French, but also the number of Huron who were participating in it, were no less after the epidemics than they had been prior to 1629. As before, the Huron probably provided close to half of the total number of furs exported from Quebec each year, which probably meant 12,000 to 16,000 skins.” (NOTE 5)

In fact, the prosperity of the Wendats is based on their ability to trade with other First Nations to obtain furs. Historian Conrad Heidenreich explains the reasons for this success:

“The development of Huron trade, and its effective execution in spite of the epidemics, seems to be founded on two fundamental factors. These were the large population of Huronia and their agricultural economy, which provided food for the traders and allowed some to specialize in this occupation. Huron agriculture was largely operated by the women. Between the spring and fall fishing seasons the men could carry out other tasks, among which trading was one.” (NOTE 6)

But this prosperity comes at a price. The more the Wendats trade with the French to obtain new products that they consider very useful, like axes, knives or other iron tools, the less time they devote to their traditional subsistence activities and production. Thus, they become dependent on the French and the fur trade (NOTE 7). To make matters worse, starting in the 1630s, the French are unintentionally the cause of a series of epidemics of influenza, smallpox, and measles that brutally decimate the Wendat population from 30,000 to 10,000 in just a few years.

A bloody and catastrophic end by fire

Just at the time when the Jesuit mission of Sainte-Marie reaches it peak, in 1649, it comes to a catastrophic end. That year, in effect, everything is conspiring against the mission. In the neighbouring Wendat villages there are now profound divisions between traditionalists and those among the Huron converted to the Catholic faith, as explains Bruce Trigger.

“There can be no doubt that the development of Christian factions in various Huron villages gave rise to new tensions that cut across the segmentary structure of the lineages, clan segments, and tribes. […] The unity of Huron society had never before been threatened in this manner and the traditionalists were faced for the first time with an organized threat to the Huron way of life.” (NOTE 8)

As well, the presence of the Europeans exacerbates the traditional rivalries between the Wendat and the Iroquois that live further south, leading to a devastating war that the Iroquois win. In March of 1649, several hundred Iroquois destroy the Wendat villages of Saint-Louis and Saint-Ignace, located just to the east of Sainte-Marie. The Jesuit missionaries Gabriel Lalemant and Jean de Brébeuf are captured, tortured, and then killed. The desperate situation in which the French find themselves force them to make a painful decision. Father Paul Ragueneau, the third and last superior of the Sainte-Marie mission, sets fire to the mission himself in June 1649 (NOTE 9).

A number of the Natives follow the French as they take refuge on Saint-Joseph’s Island, some 40 km to the northwest of the mission, which today is an Ojibway reserve called Christian Island. There the French build Sainte-Marie II, a second mission, smaller than the first. However, following a winter marked by terrible suffering, famine, and many deaths, the Jesuits, accompanied by a few hundred Wendat, head back to Quebec in the summer of 1650. Some descendants of these Wendat are still living in the Quebec City area (NOTE 10), in their reserve of Wendake, where the Huron-Wendat community proudly showcases its heritage, most notably through a museum and a traditional Huron site (NOTE 11).

For the Wendat people as a whole, their destiny will be radically altered forever. The clans and the nations are dispersed to the wind, family by family, in small groups and sometimes by entire villages. Among them, a few hundred traditionalist Wendat will be adopted by the Iroquois and become ferocious enemies of the French.

For more than two centuries, the ruins of Sainte-Marie will remain buried in the earth.

Archeological excavations, and then a reconstruction

The Huronia area will remain uninhabited until the end of the 1700’s. During the next century, the neighbouring communities of Penetanguishene and Midland are established. In 1844, the French Jesuit Pierre Chazelle visits the site and sends a description of it to his superiors in France (NOTE 12). In 1855, another Jesuit, Félix Martin, follows suit and unearths the ruins of the mission (NOTE 13). But in the short term, nothing comes of these excavations. In the 1920’s, the campaign to encourage the Vatican to canonize the eight Canadian martyrs killed in New France, including Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant, sparks great interest in the Sainte-Marie site, as this comment by the Jesuit E. J. Devine illustrates.

“ The sojourn at Fort Ste. Marie of those early missionaries, six out of the eight men who have been ranked officially among the Saints, would alone suffice to single out the spot on Georgian Bay as one of unique historic interest. […] The fragrance of their virtues still pervades the site, making it one of the holiest and most venerable shrines on this Continent (sic). The occasion of their Beatification, an event unique in the history of the Church in Canada, was seized to draw attention to Fort Ste. Marie’s claim for recognition.” (NOTE 14)

On June 21st, 1925, the Jesuits of Upper Canada say mass on the site of the ruins to celebrate the beatification of the eight martyrs (NOTE 15). The event attracts over 6,000 people. The Jesuits then purchase the hill across the road and, a year later, in 1926, the commemorative Martyr Shrine is opened and draws large numbers of pilgrims. In 1940, the Jesuits acquire the land where lie the ruins of Sainte-Marie. They are already contemplating the possibility of a complete reconstruction of the mission and, to this end, invite archeologists to come and carry out excavations. In 1941, Kenneth Kidd, working for the Royal Ontario Museum, conducts methodical archeological excavations. His team will manage to unearth the better part of the central section of the mission and compile detailed documentation. Nevertheless, in 1943 this work is halted for lack of funds.

Other excavations will be undertaken between 1947 and 1951 by Wilfrid Jury, the honorary curator of the University of Western Ontario’s Museum of Indian Archeology and Pioneer Life.

“It was about this time that a local civic booster, W. H. Cranston, began to take interest. A Baptist himself, William Herbert Cranston saw in Sainte-Marie a potential economic boom. The Martyr Shrine overlooking the archeological site attracted, by his estimates, 250,000 Catholic pilgrims annually.” (NOTE 16)

Cranston approaches the Ontario Conservative government to encourage it to develop Sainte-Marie. On March 19th, 1964, the Huronia Historical Development Council is created, with Cranston as chairman, to bring the project to fruition. The only misgivings the government has about the project stem from the Catholic and French overtones of the historic site, which it fears may upset the province’s Anglo-Saxon Protestant majority (NOTE 17).

A difficult and controversial reconstruction project

Thus, the province of Ontario decides that Sainte-Marie will become its eighth major tourist attraction at a cost of 1.25 million dollars. The site is officially opened in August 1967 by the premier of Ontario John Robarts, even though the public has already had access to the site for a year. The task of the reconstruction has proven difficult, since no plan made by the original master carpenter, Charles Boivin, has ever been found. Even the Jesuits themselves in their numerous writings offer very few descriptions of the buildings in their mission. As well, the two archeologists who conducted the excavations, Jury and Kidd, did not interpret the site in the same way.

“[…] while Kidd and others hesitated to ‘picture’ Sainte-Marie ‘as it might have been’, Jury was prepared to use his imagination. Uniquely endowed with an instinct for putting himself into the past, he applied his knowledge and experience to that instinct, and came up with theories about the site which some scholars found difficulty in accepting.” (NOTE 18)

For example, the narrow canal and lock system that runs from the Wye River into the interior of the reconstructed mission is based only on suppositions.

At the outset, in 1965, those developing the Sainte-Marie project had three main objectives: public education, an increase in tourism in the Georgian Bay area, and national unity. Bas Mason, the consultant hired to develop the project, wrote that “improved relations between Quebec (and French language Canadians generally) and Ontario (and English language Canadians) could be the greatest benefit accruing from Ste. Marie […].” (NOTE 19) Four years later, during the official opening of the Sainte-Marie museum built next to the mission, then Ontario premier William Davis confirmed that the site’s educational mandate remained a priority: “Sainte-Marie was founded to teach. Sainte-Marie was rebuilt to teach.” (NOTE 20) Visitor statistics backed up this statement. In fact, as early as 1966, the Ontario Department of Tourism reported that 17,437 students from 309 schools in Ontario and New York state had visited the site and accounted for 18% of all visitors (NOTE 21).

A living and modern history for the period

In the 1970s, Sainte-Marie can boast of being on the cutting edge of modern museology. Visitors to the site first enter a foyer where they watch a short film that features costumed non-speaking actors with a narrator recounting the tragic events. In the film’s closing sequence, the viewer sees Father Ragueneau on the screen setting fire to his own mission, followed by a close-up of the flames consuming the wooden inscription with the letters IHS (the name of Jesus, in Greek). Suddenly, the screen rises, revealing the mission’s reconstructed main entrance. Even if the film has, since then, been replaced by a slide show, the dramatic movement of the screen that opens onto the site still serves as a stunning introduction to Sainte-Marie.

Inside the mission compound, the visitor meets Aboriginal interpreters dressed in period costume as well as interpreters dressed as Jesuits, lay brothers, and donnés. They can converse, for instance, with the blacksmith as he shapes an axe head, one of the French products the Wendats, who had no knowledge of metal work prior to the arrival of the Europeans, cherished the most. In the Wendat longhouse, the visitor might meet a First Nations woman dressed in a combination of French and Amerindian clothes. This dwelling, which could accommodate 45 people, is often a feature of the site that most impresses European visitors, many of whom have a keen interest in traditional Native lifestyles. During the summer season, visitors are offered a whole array of daily activities that allow them to learn about the practices and customs of the period; for instance, fire-lighting demonstrations, the arrival of a canoe, or First Nation stories and games. Every year, the historic site also organizes special events, notably the Aboriginal Festival and Day (June 21st), the Franco-Ontarian Day (September 25th), and First Light at Sainte-Marie in December.

Sainte-Marie, a place to be passionate about the past

Sainte-Marie (NOTE 22) remains thus an important heritage site with both a history and a way of approaching it that are unique. Even if this French mission finds itself in the heart of an area where anglophones make up the majority, and even if, at the outset, it was designed as a tourist attraction with the goal of offering a new vision of Ontario’s history, this reconstructed site resonates in the collective memory of North American francophones and aboriginals. Sainte-Marie was the meeting point of two civilizations at a turning point in Canadian history; it was the stage for grand accomplishments as well as a terrible drama. It is a place that stimulates and moves, and where anyone that enters the palisaded mission to step into the 17th century never leaves indifferent.

Daniel Marchildon

A writer from Huronia, where he still resides, and the author of over twenty

publications including eleven

novels and works of history.

In 1982, he participated in Destination: Sainte-Marie, an historical reenactment of the 1,200

km canoe trip from Québec City to Sainte-Marie.

During this 45-day journey, he

played the role of Father Gabriel Lalemant.

NOTES

1. Alan Gordon, Heritage and

Authenticity: The Case of Ontario's Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons,

Canadian Historical Review,

vol. 85, no. 3 (2004), p. 531.

2. “As early as 1616, the Recollets had assumed that it would be a simpler task to convert sedentary peoples than nonsedentary ones. Thus the Hurons were assumed to be easier to convert than the Indians who lived along the shores of the Saint-Lawrence.” Bruce Trigger, The children of Aataentsic: a history of the Huron people to 1660, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1976, volume 1, p. 378.

3. Relation of what occurred in the Mission of the Hurons, from the month of June in the year 1639, until the month of June in the year 1640. Sent to Kébec, to the Reverend Father Barthelemy Vimont, Superior of the missions of the society of Jesus in new France, The Jesuit relations and allied documents travels and explorations of the Jesuit missionaries in New France, 1610-1791 : the original French, Latin, and Italian texts, with English translations and notes, Volume XIX, Quebec and Hurons: 1640, Reuben Gold Thwaites, (original edition 1898), Pageant Book Co., New York, 1959, p. 135.

4. As notes the Jesuit historian Jacques Monet: “This was a considerable population, in terms of a French population. Would there eventually have been an Amerindian colony, more or less autonomous and French, even a mixed-blood people, here in what is now the Georgian Bay area? Here we would have had a French province of Canada at a time when Montreal and Quebec where but small villages. It is interesting to speculate about what would have happened had they (the French) not left at that time.” (our translation from the original French) Jacques Monet speaking in La Huronie, a documentary film in French by Denis Boivin, Québec, Productions Kwé Kwé, 2009. Also, in one of the very rare contemporary articles published in Quebec about Sainte-Marie, Bernard Racine recognizes that: “The history of Huronia constitutes the first chapter of the history of Ontario and a forgotten chapter of the history of Quebec, in which were involved a great many of the first citizens of the city of Quebec.” (Our translation from the original French.) Bernard Racine, « On a marqué l’été dernier le 350e anniversaire de Sainte-Marie-des-Hurons», L’Action nationale, vol. 80, no 5, May 1990, p. 685.

5. Trigger, op cit., volume 2, p. 605.

6. Conrad Heidenreich, A History and Geography of the Huron Indians 1600-1650, McClelland and Stewart, 1971, p. 279.

7. Sylvie Savoie, Les gens de la péninsule, Les Hurons de Wendake, Québec, Varia, 2008, p. 27.

8. Trigger, op. cit., volume 2, p. 721.

9. Father Superior Ragueneau describes this sad scene on June 4th, 1649 in the following manner: “ […] But on each of us lay the necessity of bidding farewell to that old home of sainte Marie, (sic) — to its structures, which, though plain, seemed, to the eyes of our poor Savages, master-works (sic) of art; and to its cultivated lands, which were promising us an abundant harvest. That spot must be forsaken, which I may call our second Fatherland, our home of innocent delights, since it had been the cradle of this Christian church; since it was the temple of God, and the home of the servants of Jesus Christ. Moreover, for fear that our enemies, only too wicked, should profane the sacred place, and derive from it an advantage, we ourselves set fire to it, and beheld burn before our eyes, in less than one hour, our work of nine or ten years.”

The Jesuit relations and allied documents travels and explorations of the Jesuit missionaries in New France, 1610-1791 : the original French, Latin, and Italian texts, with English translations and notes, Volume XXXV, Hurons, Lower Canada, Algonkins: 1650, Reuben Gold Thwaites (original edition 1898), Pageant Book Co., New York, 1959, p. 81 and 83.

10. «The Wendats of Roreke are those that take the road leading them northeast after the fall of the Wendat confederation. A continuous flow of individuals and families coming from the other groups join the three hundred that arrive in the Quebec City area in 1650.» (Our translation from the original French.) Louis-Karl Picard-Sioui, (dir.) Territoires, mémoires, savoirs : Au cœur du peuple wendat, Wendake (Québec) éditions du CDFM, 2009, p. 20.

11. For more information, see : About the community (in French): http://www.wendake.ca/ ; The Huron-Wendat Museum, opened in 2008: http://www.hotelpremieresnations.com/musee/concept.php?langue=en ; The Traditional Huron site « ONHOÜA CHETEK8E », the most authentic reconstruction of an Indian village in Quebec: http://www.huron-wendat.qc.ca/index-en.html ; Tourism Wendake, established by the Council of the Huron Wendat Nation in August 2006: http://www.tourismewendake.com/default_eng.aspx.

12. E. J. Devine, s. j., Old Fort Ste. Marie: home of the Jesuit martyrs 1639-1649, second edition, 1947 (originally published in 1926), Martyr Shrine, p. 45.

13. Many years later, Félix Martin will describe the site he visited in the following manner: “The ruins of this French construction are still visible in the middle of the forest. We mapped them out in 1859. The regular part of the fort built of stone is still 1.5 meters above the ground. The trenches that lead to the river and served in the manner of a port for the canoes of the Savages are easily recognizable. The vast salient, that can be observed from the south, also contains traces of an earthwork parapet along the trench. But the residence within the confines of the fort must have been made of wood, for there remains but a few ruins of its chimney.” (Our translation from the original French.) Félix Martin, Hurons et Iroquois : le P. Jean de Brébeuf, sa vie, ses travaux, son martyre, Paris: G. Téqui, 1877. Scanned from a CIHM microfiche of the original publication held by the National Library of Canada, and available on line at: http://www.canadiana.org/view/09932/193, p. 191-192.

14. Devine, op. cit., p. 51 and 52.

15. The eight martyrs will be canonized June 29th, 1930.

18. Robert Runcie Inglis, Preserving History: A Study of History Museums and Historic Sites, with Special Reference to Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, Midland, Ontario, Masters thesis, University of Toronto, History and Museology Department, 1972, p. 74.

22. The contemporary name given to the historical site has an interesting story. First of all, for many years the general public continued to use the incorrect name Fort Sainte-Marie, forcing the interpreters to emphasize the fact that the site is a fortified mission and not a commercial or military fort. During the reconstruction, the Ontario government decided to name the new mission Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, which, in French became Sainte-Marie-au-pays-des-Hurons. However, during the period of New France, the mission was referred to, notably in the Relations written by the Jesuits, as Sainte-Marie aux Hurons, or the Résidence Sainte-Marie.

Bibliographie

Desjardins, Paul, La résidence de Sainte-Marie-aux-Hurons, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, University of Sudbury, 1966, 46 p.

Devine, E. J., s. j., Old Fort Ste. Marie: home of the Jesuit martyrs 1639-1649, second edition, 1947 (originally published in 1926), Martyr Shrine, Midland, 58 p.

Gordon,

Alan, Heritage and Authenticity: The Case of Ontario's

Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons,

Canadian Historical Review vol. 85, no. 3 (2004): pp. 507-531

Heidenreich, Conrad, A History and Geography of the Huron Indians 1600-1650, McClelland and Stewart, 1971, 337 p.

Inglis, Robert Runcie, Preserving History: A Study of History Museums and Historic Sites, with Special Reference to Sainte-Marie Among the Hurons, Midland, Ontario, Masters thesis, University of Toronto, History and Museology Department, 1972, 105 p.

Jury, Wilfrid, and Elsie McLeod Jury, Sainte-Marie among the Hurons, Toronto, Oxford University Press, paperback version 1965 (first printing 1954), 128 p.

La Huronie, documentary film by Denis Boivin, in French, Québec, Productions Kwé Kwé, 2009. http://www.k8e.ca/default.htm

Martin, Félix, Hurons et Iroquois : le P. Jean de Brébeuf, sa vie, ses travaux, son martyre, Paris: G. Téqui, 1877. Scanned from a CIHM microfiche of the original publication held by the National Library of Canada, and available on line at: http://www.canadiana.org/view/09932/193,

Picard-Sioui, Louis-Karl (Dir.) Territoires, mémoires, savoirs : Au cœur du peuple wendat, Wendake (Québec) éditions du CDFM, 2009, 44 p.

Racine, Bernard , « On a marqué l’été dernier le 350e anniversaire de Sainte-Marie-des-Hurons», L’Action nationale, vol. 80, no. 5, May 1990, pp. 684-690.

Savoie, Sylvie, Les gens de la péninsule, Les Hurons de Wendake, Québec, Varia, 2008, 44 p.

Stoskopf Harding, Karen, Architecture française en Ontario, Quatre exemples marquants de l’œuvre de nos premiers bâtisseurs, Sudbury, Prise de Parole, 1987, 107 p.

Thwaites, Reuben Gold, The Jesuit relations and allied documents travels and explorations of the Jesuit missionaries in New France, 1610-1791 : the original French, Latin, and Italian texts, with English translations and notes, Volumes XX to XXXV, (original edition 1898), Pageant Book Co., New York, 1959.

Trigger, Bruce, The children of Aataentsic: a history of the Huron people to 1660, 2 volumes, Montreal, McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1976, 913 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Carte de la diaspora

Carte de la diaspora

ouendate, dispe... -

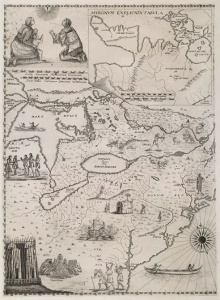

Carte de la Nouvelle-

Carte de la Nouvelle-

France, 1657 -

Extérieur de la forge

Extérieur de la forge

à Sainte-Marie... -

Guide animateur forge

Guide animateur forge

ron à Sainte-Ma...

-

Inauguration d'un mon

Inauguration d'un mon

ument élevé sur... -

Inauguration d'un mon

Inauguration d'un mon

ument élevé sur... -

L’arrivée d’un canoë

L’arrivée d’un canoë

à Sainte-Marie ... -

La forge à Sainte-Mar

La forge à Sainte-Mar

ie-au-pays-des-...

-

Le couvent pionnier d

Le couvent pionnier d

es soeurs de Sa... -

Le guide des visiteur

Le guide des visiteur

s du site histo... -

Le nouveau couvent de

Le nouveau couvent de

s soeurs de Sai... -

Ouverture officielle

Ouverture officielle

du site de Sain...

-

Sainte-Marie chez les

Sainte-Marie chez les

Hurons (vers 1... -

Sainte-Marie-au-pays-

Sainte-Marie-au-pays-

des-Hurons : en... -

Sainte-Marie-au-pays-

Sainte-Marie-au-pays-

des-Hurons : en... -

Vue aérienne de Saint

Vue aérienne de Saint

e-Marie. À son ...

Hyperliens

- Sainte-Marie TV commercial (15 seconds)

- Exhibit about Sainte-Marie on the Ontario Archives web site

- Exhibit (in French): Le destin tragique de Sainte-Marie-au-pays-des-Hurons, part of La présence française en Ontario : 1610, passeport pour 2010, posted by the Centre for Research on French-Canadian Culture of the University of Ottawa

- The historical site Sainte-Marie-among-the-Hurons