From Saint Paul des Métis to Saint Paul: A Patch of Franco-Albertan History

par Kermoal, Nathalie

The year 2009 marked the centennial of the year in which Saint Paul des Métis was opened to French-Canadian colonization. While the community had existed since 1896, it is interesting to note that it is the anniversary of the arrival of French Canadians in the region that is celebrated, while the Métis background of the community is passed over in silence. The decision to open this Métis colony to French Canadians has been the subject of debate among historians over the years, but for the Métis families who were compelled to leave Saint Paul to settle elsewhere, the event has left lasting scars. Over time, Saint Paul became a dynamic community determined to preserve the town’s French language and francophone culture, but also a town known for its multiculturalism.

A Vibrant Francophone Community in Alberta

Today, Saint Paul has a population of nearly 5,500 inhabitants. Located northeast of Edmonton, Saint Paul is first and foremost a town that provides services to the surrounding villages, but it is also a cultural centre that reflects the ethnic diversity of the region. Every year, the town is host to many cultural events—among them, a sugar shack organized by the Association canadienne-francaise de l'Alberta, a Ukrainian pierogi supper, a powwow at the Saddle Lake First Nation and the finals of the Lakeland Rodeo Association (LRA) rodeo.

Although the population has diversified over time, Saint Paul is still a town where the primary language is French and that offers many services in French. Moreover, the Saint Paul regional branch of the Association canadienne-française de l’Alberta (ACFA) plays a central role in promoting the interests of the community and actively contributes to its overall development. Saint Paul’s dynamism is expressed through political action, but also through cultural initiatives. Following adoption in 1982 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, a small group of francophone parents decided to establish a French school, l’École du Sommet, which opened its doors in September 1990. In November 1993, the government of Alberta gave control of the francophone school system to the French-speaking people. The Conseil scolaire Centre-Est was established. This school board administers schools in Saint Paul, Plamondon, Bonnyville and Cold Lake. Its headquarters are in Saint Paul.

Francophones are also very active in the cultural arena. Several well-known Albertan artists hail from Saint Paul and the Saint Paul region. Louise Piquette, a multidisciplinary artist from Saint Paul, draws inspiration for her work from family members, friends, and acquaintances. Margo Lagassé, self-taught sculptor and potter, and Crystal Plamondon (from Plamondon), a singer-songwriter who performs country, Cajun, and folk music, have both gained international recognition for their work. In addition, Les Blés d’Or, established in 1973, was the first dance company to teach traditional French-Canadian dance in Alberta. This company is also behind a research project on the history of Franco-Albertans entitled Héritage franco-albertain. The project yielded a sound collection that is now archived at the Campus Saint-Jean in Edmonton. The collection includes life stories, tales, songs, photographs, and a variety of other documents pertaining to the pioneers who made their mark on the history of Saint Paul and the surrounding communities. As part of this movement to preserve Franco-Albertan heritage, and to stimulate interest in the history of French-speakers in the region, the Saint Paul Historical Museum was established in 1979. This bilingual museum organizes exhibitions on the community of Saint Paul as it is today but also on the beginnings of the town, thus making the richness of the town’s Métis and Francophone past available to the public.

The Beginnings of Saint Paul des Métis: A Philanthropic Project

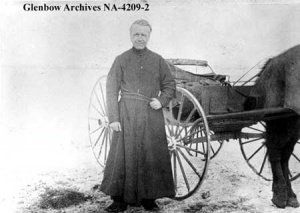

Historically, Saint Paul is an interesting project insofar as it resulted from the desire of one man—Father Albert Lacombe—to establish a community for the Métis people. He played a central role in ensuring that the project, his own brainchild, became a reality, obtaining financing from both the federal government and philanthropic benefactors. Father Lacombe knew the Métis people well. In 1849, when he was a young priest in Pembina, he had followed them into the plains for the great buffalo hunt. When he arrived in the region around Edmonton in the 1850s, he was once again in contact with Métis people at Lac Ste. Anne, then again in 1861 à St. Albert. The Métis often accompanied him when he travelled, and they provided essential labour for missions across the province, in particular when the mission involved transporting merchandise. In short, Father Albert Lacombe devoted a substantial part of his life to working with the native people of Alberta. Moreover, he was quick to complain to his superiors when other occupations kept him from his “Indian” missions for too long. As well, it is evident in his correspondence that he had a great deal of respect for the Métis people; however, this respect was often mixed with moralizing and paternalistic musings.

In 1895, saddened by the destitution of Métis people in the Canadian West, Father Lacombe proposed in his plan for the “redemption” of the Métis people to establish a “reserve” to help them to make the transition from a nomadic to a sedentary lifestyle. Thus, in his vision, the Métis people, like French Canadians, would become good farmers. Over time, as European-Canadian settlers colonized the West, the reality of the Métis people’s daily existence underwent a gradual transformation. The events of 1869 at Red River Colony, then the Métis Uprising at Batoche in 1885, had had an impoverishing effect on the Métis, leading to their dispersal across the Prairies and, ultimately, to their marginalization as a people.

Father Lacombe was witness to the failure of the scrip system of land grants imposed by the federal government for the purpose of extinguishing the aboriginal title of the Métis people, and to the breaches of trust and fraudulent practices to which the Métis fell victim. Father Lacombe therefore proposed an alternative to Macdonald’s Conservative government, then to Wilfrid Laurier’s Liberal government. In a letter sent to Prime Minister Laurier in 1896, he wrote [translation]: “Considering that this Métis nation is becoming ever more destitute and poor as its contact with white settlers increases, and that the future of this people would appear to be growing darker, we thought that we should make an effort towards redemption in favour of these people, to whom we are devoted and attached by the ties of religion and patriotism.” He thought that in order to save the Métis from decline, it would be necessary to establish an impermeable zone between them and the white settlers. Despite budget restrictions, the federal government extended a grant of $2,000 to Father Lacombe.

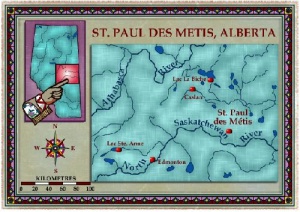

Saint Paul, located near the Saddle Lake Indian reserve was established, then, in 1896 on 92,160 acres of land that had been set aside for the Métis by the federal government. The land remained the property of the Crown; yet Father Lacombe had signed a 99-year lease with the government for $1 per year. The lands could neither be sold nor mortgaged. Four other lots were set aside for the church, the school, and the rectory. Each family was to receive 80 acres in addition to livestock, farming machinery, and access to communal lands for the production of hay and timber and to use as pastureland. In addition, to avoid problems, alcohol was banned, and anyone who brought alcohol into the colony was to be expelled.

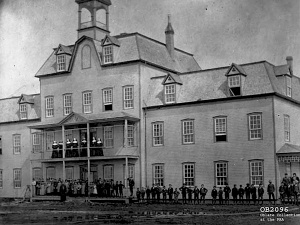

Father Lacombe, who by this time was getting on in years, entrusted the task of organizing and maintaining the colony to Father Adéodat Thérien. To the three families already established on these lands in 1896 (the families of Simon Desjarlais, Joseph Cardinal and Pierre Desjarlais), 30 new families from around Alberta and Saskatchewan were soon added. In 1897, the little colony comprised 50 families. A chapel, a rectory, a sawmill, and a grain mill were built; then the Oblate missionaries, assisted by the Sisters of the Assumption, decided to establish a boarding school to provide an education to the children of the community.

A Reality fraught with Hardship

Despite the successes of the early years, a number of problems eventually arose to undermine the efforts of the missionaries and the Métis. Besides prairie fires and hail, the community endured a fire that destroyed the school on 15 January 1905. Additional hardships included a lack of funds, machinery and livestock, and the relatively great distances from one farm to the next. In 1908, the lease was terminated, and one year later, the colony was opened to French Canadians. According to Katherine Hughes, Father Lacombe’s biographer, the aging missionary was quite distressed by the troubles that befell the inhabitants of Saint Paul des Métis. In his own words [translation]: “Dear Lord, how sad this is!...No one today can understand my unhappiness, my sorrow, my disillusionment. I will go down to my grave with an affliction in my soul. My poor Métis! ... I can only weep in secret.”

In the eyes of the federal government, the project had been destined to fail, as the Métis were not fully engaged and had not come in sufficient numbers to settle in Saint Paul. Because of the lack of capital, the only alternative was to open the colony to new settlers who would be able to survive by working the land and who required no federal assistance. As for the Métis, in their estimation, the Church, the government and the French Canadians bore responsibility for the failure of the colony, the promises of the early years apparently having given way to greed and falsehood. Disgruntled at not having been consulted, they decided to send a petition to Ottawa denouncing the opening of the colony to French-Canadian settlers, but this petition went unanswered.

From Métis colony to French-Canadian Community

Father Thérien, realizing that it would be impossible to continue to manage the colony according to the tenets set forth by Father Lacombe, recommended transforming the original plan by opening up the colony to white settlers. One of the most famous photographs of the time is most certainly the photograph of French Canadians lining up in front of the door at the Edmonton Dominion Land Office. For three days, 500 of them waited day in and day out to have their lot number registered. On 10 April 1909, 450 homesteads were recorded. Although the pioneers were mostly French Canadians from Quebec, there were Métis among them, such as the Garneau family, who wished to remain in the region, as well as settlers from the Ukraine and from Great Britain. Among the family names of the pioneers, we find such names as Beaudin, Carrier, Doucet, Duteau, Fontaine, Girard, and Hurtubise, to name only a few. With this fresh increase in the population, the town quickly gained momentum. While in 1909, Saint Paul des Métis was no more than a hamlet, it would take only 20 years or so for it to become a town, which shortened its name to Saint Paul in 1936. A town council was established, followed gradually by a number of other institutions.

The inhabitants relied primarily on farming, as the land in the surrounding regions was particularly fertile. However, in addition to this agrarian activity, services began to emerge—hotels, a timber yard, a post office, a telegraph station, and general stores. Medical care was provided by Dr. Jean-Baptiste Charlebois, who went from home to care for the ailing. Depending on the distance, he travelled on foot or on horseback. When his workload became too great for one man, a second doctor, Dr. Gagnon, joined him in1910.

Moreover, as was the case for many parishes at the time, Saint Paul suffered the ravages of the flu epidemic of 1918, which left many fatalities in its wake. This crisis underscored the urgency of the need to build a hospital. However, it would be another 10 years before the project was completed. In 1930, Sainte Thérèse Hospital, still in existence to this day, was established, with a capacity of 60 beds.

The Railroad and Economic Development

At the turn of the 20th century, many towns and villages owed their existence —and to a certain extent their survival— to the railroad. For the citizens of Saint Paul, the train was a sine qua non for the economic development of their community. In 1914 construction began on a new railway line to the north of Edmonton; however, due to a shortage of workers, construction came to a halt in 1919 with the line stopping at Spedden, some 48 kilometres short of Saint Paul. Aware of how important the train was for shipment of merchandise, animals, and people, the inhabitants of Saint Paul decided to lay the remaining track themselves. In 1920, the first train rolled into town. Saint Paul hired its first stationmaster, J. A. Fortier, and built its first grain elevator soon thereafter.

Grain elevators, veritable icons of the Prairies, dominated the western skyline for over a hundred years. Indeed, grain elevators were a sign of the economic viability of a community and the agricultural strength of the surrounding region. A strictly utilitarian structure designed to receive, store, and expedite grain in bulk, it was the first step in a process of marketing that involved transporting the grain from the producer’s farm to world markets. It provided farmers with a means to save time and money by outsourcing the task of shipping their precious commodity to distant destinations. When Saint Paul’s last grain elevator was closed in 2002, trucks having gradually replaced trains as the preferred vehicle for shipping grain, the event marked the end of an era.

To this day, farming is at the core of the economic activity of the town of Saint Paul, but today’s farms are a far cry from those of olden times, small family farms having all but disappeared to make way for large corporate farms. Saint Paul had to diversify its economic activities: the oil and natural gas sectors, as well as the construction industry, gave Saint Paul the wherewithal to continue to offer services to neighbouring communities. As well, the region relies on certain natural resources—such as salt, peat, timber, and gravel—to provide employment to the members of the community.

Welcoming tourists…wherever they come from!

Always alert to new ways of diversifying its economy, the community of Saint Paul decided to develop its potential as a tourist destination by encouraging development of parks for the enjoyment of vacationers and hikers. Saint Paul is unique, however, among the many towns or rural municipalities that seek to capitalize on the proximity of lakes to attract tourists, due to a most unusual project! In 1967, to commemorate the centennial of Canadian Confederation, Saint Paul opted to make a name for itself by means of a very original project—namely, construction of a landing pad for Unidentified Flying Objects (UFO). This project led Saint Paul to build a tourist information centre and an exhibition on UFOs in the 1990s. The landing pad is marked by a plaque on which the following text is inscribed:

“Republic of Saint-Paul (Stargate Alpha): The area under the world’s first U.F.O. landing pad was designated international by the town of St. Paul as a symbol of our faith that mankind will maintain the outer universe free from national wars and strife. That future travel in space will be safe for all intergalactic beings. All visitors from earth or otherwise are welcome to this territory and to the town of St. Paul.”

This landing pad, which some might qualify as eccentric, nonetheless drew the attention of such notables as Queen Elizabeth II and Mother Teresa.

A Community that is Here to Stay

The tenacity and hard work of the pioneers of Saint Paul were such that, over the years, the town and region became one of the jewels of francophone Alberta. From its beginnings as an impermeable zone to protect the Métis from the influence of white settlers, Saint Paul evolved into a dynamic community determined to preserve the French language and francophone culture. But the community is also known for its multiculturalism, with citizens originating from 17 different countries around the world. Still, these accomplishments would not have been possible without the initial vision of Father Albert Lacombe and the legacy that the Métis left behind. All of these people contributed in their own way to making Saint Paul the town that it is today.

Nathalie Kermoal

Associate Professor, University of Alberta

An earlier version of this article appeared in the weekly Franco-Albertan newspaper Le Franco on 26 June 2009 in honour of the centennial of Saint Paul des Métis being opened up to French-Canadian colonization. This updated version includes some minor modifications.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Carte de Saint Paul d

Carte de Saint Paul d

es Métis, Alber... -

Carte postale de l'Al

Carte postale de l'Al

berta -

Carte postale de St.

Carte postale de St.

Paul de Métis -

Cathédrale de Saint-P

Cathédrale de Saint-P

aul, Alberta, 2...

-

Coopérative et statio

Coopérative et statio

n service à Sai... -

Couvent de Saint Paul

Couvent de Saint Paul

des Métis, Alb... -

Fermiers métis établi

Fermiers métis établi

s à St. Paul De... -

Fête Franco-Albertain

Fête Franco-Albertain

e à Saint-Paul,...

-

Fête Franco-Albertain

Fête Franco-Albertain

e à Saint-Paul,... -

Hotel Lavoie à Saint

Hotel Lavoie à Saint

Paul, Alberta, ... -

L'artiste Crystal Pla

L'artiste Crystal Pla

mondon -

La désormais célèbre

La désormais célèbre

piste d’atterri...

-

Le père Albert Lacomb

Le père Albert Lacomb

e en Alberta, 1... -

Le père oblat Albert

Le père oblat Albert

Lacombe en 1911... -

Le père oblat d'origi

Le père oblat d'origi

ne polonaise An... -

Mgr Vital Justin Gran

Mgr Vital Justin Gran

din, OMI

-

Panneau apposé à l'hô

Panneau apposé à l'hô

tel Hansen, aut... -

Panneau du Centre cul

Panneau du Centre cul

turel de Saint-... -

Père Albert Lacombe,

Père Albert Lacombe,

OMI, vers 1890 -

Vieille ferme près de

Vieille ferme près de

Saint Paul, Al...