Chaudière Falls in the Outaouais Region

par Boucher, Louise N.

Article disponible en français : Chutes des Chaudières en Outaouais

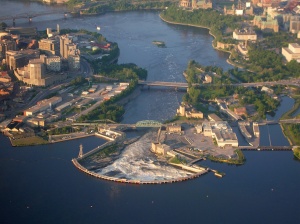

The Chaudière Falls Site

Situated in Canada’s National Capital Region, the area known as the Chaudière straddles the Quebec-Ontario border and parts of the cities of Gatineau and Ottawa. In addition to the Falls, the site includes a semi-circular dam, a section of the Ottawa River, islands (Chaudière, Victoria, Amelia, and Albert, as well as Philemon, now a peninsula), two river banks, two bridges (Chaudière to the west and Portage to the east), walking trails, an aboriginal interpretive centre, industrial buildings no longer in use, small power stations, and a recently-closed paper mill. The Falls themselves are situated mainly on the Quebec side of the border, with a smaller section in Ontario. The site is sandwiched between two historic neighbourhoods, Ottawa’s Le Breton Flats to the south and Vieux-Hull in the City of Gatineau to the north.

Heritage Designations of the Site

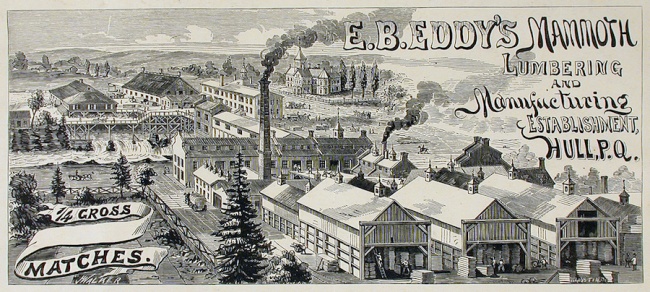

The Chaudière district is a microcosm of Canadian history as it relates to French-speaking America; however, the heritage designations it has received have been piecemeal. Some buildings, constructed by the E.B.Eddy Company, looking out on Laurier Street in Gatineau, were designated as heritage buildings by the Government of Quebec. The historical significance of these protected buildings rests on their ability to recall the industrial history of the Outaouais region in the 19th century. Not far from there, the Chaudière Portages Trail (also called the Voyageur Trail) was designated a National Historic Site in 1927 by the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada. On the Ontario side, the Victorian-style Bronson Company Office, the Willson Carbide Mill and the Ottawa Electric Railway Company Steam Plant have been designated Recognized Federal Heritage Buildings by the Federal Heritage Buildings Review Office, while the Hydro Ottawa Generating Station 2 has been named a Classified Federal Heritage Building by the same body.

Three well-know figures associated with the site also appear as “Persons of National Historic Significance” in the Parks Canada Directory of Federal Heritage Designations. Born in Vermont, Ezra Butler Eddy produced great quantities of matches and paper in the Quebec sector of the Chaudière . Thomas Leopold “Carbide” Willson, born in Upper Canada, had a cottage on Meech Lake (where the Meech Lake Accord was negotiated) in Quebec. At the Chaudière, Willson manufactured calcium carbide, used for soldering and, beginning in 1903, in acetylene cutting torches (Note 1). Philemon Wright, who came to Lower Canada from the United States to found what would later become Hull, then Gatineau, pioneered the timber trade in the Ottawa Valley, the first man to transport timber by raft.

In addition to these historical relics and figures, a body of landscape art also plays a role in preserving this valuable heritage, through representations of the Chaudière site in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries. These works are held by various archives and museums, such as the McCord Museum, the National Gallery of Canada, and Library and Archives Canada. The site has been memorialized in nearly a hundred works created by some forty artists.

Settlement of the Site

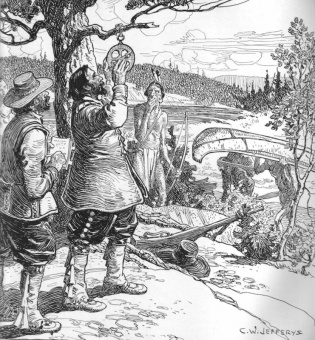

Before the current industrial buildings covered the site, there were various periods of settlement, beginning with the First Nations. Illustrator Charles W. Jeffreys evoked this period in his depiction of an Algonquin tobacco ceremony held near the Falls.

In spite of its somewhat Hollywood-like character, this watercolour, painted around 1930, does show native people practising their religion near the main Falls. This could no longer happen today in the area adjacent to the Falls because the land is under private ownership of industry and the dam contains the falls (bleeds them, according to the Algonquins). The tobacco ceremony portrayed in this Jefferys painting was described by Samuel de Champlain in this way: Having carried their canoes to the foot of the fall, they assemble in one place, where one of them takes up a collection with a wooden plate into which each puts a piece of tobacco. After the collection, the plate is set down in the middle of the group and all dance about it, singing after their fashion. Then one of the chiefs makes a speech, pointing out for years they have been accustomed to make such an offering, and that thereby they receive protection from their enemies; that otherwise misfortune would happen to them […]. » (Note 2). In the second part of his 1613 work, Champlain also notes that the native word for the Falls (the Saut) was Asticou, meaning cauldron or kettle. (Note 3)

After Champlain, the name Chaudière was adopted by various authors, including Anglophone artists who preferred the French term to Great and Little Kettle (In French, the use of the plural Chaudières implies that there are both large and smaller falls). Charles W. Jeffreys presented his image of Champlain’s passage in an illustration of the explorer setting up along the Ottawa River.

Library and Archives Canada has a photograph of another, almost identical work by the same artist, catalogued as: Champlain taking his position at the Chaudière Falls in 1613 (Note 4). The reference to Chaudière Falls in this title suggests that Jeffreys placed Champlain at that exact spot on the Ottawa River in the above illustration. While the dazed expression of the aboriginal is both unrealistic and unfortunate, the moccasins and leggings worn by Champlain are genuine, proof that the Europeans borrowed from the First Nations to help them in their exploration and in the fur trade.

At the onset of British Rule, the colonization of the township of Hull (until then used only for the fur trade) began, with the arrival of the Loyalists pledging allegiance to the Crown. The first community was established in the early 1800s on the north shore of the river, in Lower Canada, by colonists from Massachusetts. On the other side of the river, in Upper Canada, a few sparse communities appeared but the growth of an actual town began only in 1826, with the construction of the Rideau Canal. This is illustrated in a drawing by Colonel John By, founder of Bytown, showing a military camp being built a kilometre away from the Chaudière Falls by workers displaying the most recognizable French-Canadian symbols, the red tuque and the arrowhead sash (ceinture fléchée), together with First Nations canoes and British military tents. The drawing is proof of the mix of French, British and First Nations communities at the site, clearly illustrating its multicultural character.

To facilitate the transportation of the goods needed to build the canal, a series of bridges were built between Bytown and Wright’s Town (which would become Hull). According to the account of Benjamin Sulte, illustrated by Henri Julien, it was on the stone parapet of one of these bridges that the legendary raftman and defender of Francophones, Jos Montferrand, defeated 150 shiners. (Note 5) Sulte made his story very believable by providing a date for the donnybrook (1829) and, even more so, by noting that it had been told to him by one of the witnesses on the scene, “Mr Bastien, a Montreal city policeman” (Note 6).

In the employ of lumber barons, including Joseph-Ignace Aumond, many other Francophone, Anglophone and sometimes aboriginal raftmen had to travel through the Chaudière. Coming from the northern forests, they first had to navigate the Calumet Rapids. Arthur Heming’s painting of this passage is a moving work, particularly when it is considered in light of this passage by J-C Taché:

“The rafts are built with this in mind; a small platform of sorts is erected in the middle and the men climb up on it once they have entered the terrible currents, to avoid being swept away by the water rushing over the floor of the raft. It is terrifying to see these men entering this dangerous passage: at first, they paddle fiercely, on one side then on the other, following the orders of the Iroquois guide who is their pilot; then, once the raft is engaged in the channel and man’s efforts are for naught, the oars are pulled out and, throwing themselves on the mercy of the powerful waters, the raftmen clamber onto the platform and cling to it, as they and their craft rush toward the roaring and swirling torrent below.” [TRANSLATION] (Note 7)

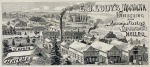

While the French-speaking population of Hull had earlier been only a minority, it grew considerably in the 1870s, with the arrival of workers hired by Ezra Butler Eddy’s sawmills and manufacturing plants, making the Chaudière an important industrial area. The contribution of the female match company workers, the allumettières, is particularly noteworthy; they marked the collective memory in such a way that one of the most important boulevards in Gatineau now bears their name. The first allumettière was Eddy’s wife, Zaïda Diana Arnold, who showed the women and children of the region how to package matches at home. The match factory Eddy built was so productive that it dominated the Canadian market from 1879 onward. Economic reports suggest that as many as 400 women, most of them Francophone, worked in the Eddy match factories. Paid less than men and required to work evening shifts, they wanted women supervisors. In 1919 and in 1924, the women workers stood up to their Anglophone bosses and organized two strikes to improve their working conditions. (Note 8).

At the turn of the 20th century, the E.B. Eddy Manufacturing Company began to produce paper and, at the height of its production, it rolled out up to 20 tons a day.(Note 9). Smoke from this paper mill’s stack can be seen rising on the right-hand side of Henri Fabien’s painting, while the smoke seen just left of centre comes from the businesses of John Rudolphus Booth, purchased by Eddy in 1946 (Note 10). Beginning in 1871, 30,000,000 board-feet were produced annually in the Booth Company mills (Note 11). It expanded so considerably in the 20th century that Booth was considered to be the largest company in the world owned by a single man in the 1920s (Note 12). The company, located on the border, ensured its prosperity by hiring between 1,000 and 2,000 residents of Hull, as well as workers from Ottawa’s Lower Town. Workers from Hull actually preferred working in Ottawa because they received better benefits when they were injured. (Note 13).

Current State of the Site

Today, the various buildings seen on the Fabien painting are still present on the site, with the exception of the grain silos and the smoke stacks. Some of the structures are crumbling while others are well maintained, in keeping with their heritage designation. Despite its significant historical value, the site as a whole has never been formally recognized. The recognition of some individuals, art works and relics constitutes a fragmented heritage designation. However, there remain other hundred-year-old relics that should be protected, including the semi-circular hydroelectric dam, a pallet workshop, the J.R. Booth cardboard factory, other Eddy Company buildings, and the former timber and crib slide channels. While some of these are on the Ontario side of the river, most of the people working there were French-speaking; the sites are, therefore, part of the heritage of French-speaking America.

Future of the Site

In February 2012, the Domtar Company (which succeeded Eddy) demolished one of the J.R Booth buildings, constructed in1903, that it considered obsolete (Note 14). The Eddy buildings barely escaped demolition, thanks to the concerted efforts of concerned citizens (Note 15). As long as heritage designation applies only to individual buildings, the spirit of the site, which is worthy of preservation, will not be protected. The site as a whole is more significant than its parts. For this reason, it is to be hoped that steps will be taken to end the fragmented approach to designation so that the entire area will become a heritage site in the near future.

Louise N. Boucher

University of Ottawa

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

An elucidation of the

An elucidation of the

three position... -

Champlain as represen

Champlain as represen

ted by C.W. Jef... -

Chaudière Falls and B

Chaudière Falls and B

ridge [on the O... -

Chaudière Falls, Cana

Chaudière Falls, Cana

da West

-

Chute de la Grande Ch

Chute de la Grande Ch

audière sur la ... -

Chutes Chaudière et H

Chutes Chaudière et H

ull vers 1853 -

Des Canadiens françai

Des Canadiens françai

s érigent, en 1... -

Description de la cér

Description de la cér

émonie du tabac...

-

Description de la cér

Description de la cér

émonie du tabac... -

Désignation de la chu

Désignation de la chu

te Chaudières s... -

Les chutes Chaudière,

Les chutes Chaudière,

vues de Bridge... -

Les chutes de la Chau

Les chutes de la Chau

dière et le pon...

-

Near the Chaudiere Fa

Near the Chaudiere Fa

lls, Ottawa, 13... -

No. 2. View of the Fa

No. 2. View of the Fa

lls of Chaudièr... -

Offering of tobacco n

Offering of tobacco n

ear the main Ch... -

Ottawa: Scow Shooting

Ottawa: Scow Shooting

the Chaudière ...

-

Radeau sur les rapide

Radeau sur les rapide

s du Calumet, 1... -

The Chaudière site: i

The Chaudière site: i

n the centre, t... -

The match factory at

The match factory at

the foot of the... -

View of Philemon Wrig

View of Philemon Wrig

ht’s mill and t...

Catégories

Notes

1. Paton, Jennifer, “Willson, Thomas Leopold”, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, 1901-1910, vol XIII, Ottawa, BAC; Québec, Université Laval; Ontario, University of Toronto, 2000.

2. Les voyages dv sievr de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine; quatriesme Voyage, livre 1 et 2, Paris, Iean Berjon, 1613, p. 46-47.

3. Champlain 1613, 4e voyage, deuxième partie, p. 23. We did not find the term asticou in any Algonquin, Huron, Montagnais or Iroquois dictionary we consulted. However, the Jesuit, Pierre Biard, mentions it as the proper name of an Algonquin chief who apparently became an Abenaki (1611: 8; 297 in Thwaites). According to Maurault (1866: 95; idem), the name of Chief Asticou means caribou. Further research needs to be done.

4. Library and Archives Canada, mikan 2956113. It appears that this work was accidentally destroyed; we were able to see the photograph but were unable to obtain the right to reproduce it from the CCN. The work in the photograph is almost identical to the one in Jeffreys’ book, reproduced above.

5. The shiners were Irish lumber workers who considered French Canadians their rivals. “Their favourite sport seems to have been to throw their rivals [the French Canadians] into the Great Kettle at the Chaudiere” Gillis, Sandra J., The timber trade in the Ottawa Valley, 1806-54, Ottawa, Parks Canada,1975: 118.

8. Lapointe 1979 ; Vincent-Domey 1994 et 2000.

11. Benidickson, Jamie, « Booth, John Rudolphus, Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online, 1901-1910, vol XIII, Ottawa, BAC; Québec, Université Laval; Ontario, University of Toronto, 2000.

13. Vincent-Domey 1994, p. 295.

14. Joanne Chianello, Ottawa Citizen, 25 février 2012, p. 1.

Bibliographie

Boucher, Louise N., Interculturalité et esprit du lieu : la chute des Chaudières, Thèse de doctorat sous la direction d’Anne Gilbert, Ottawa : Université d’Ottawa, 2012.

Boucher, Louise N., « Les significations d’un lieu de mémoire : le paysage des chutes Chaudières ». Gilbert A. et al. (dir.): Entre lieux et mémoire. L’inscription de la francophonie canadienne dans la durée. Université d’Ottawa, 2009, pp. 193-219.

Champlain, Samuel de, Les voyages dv sievr de Champlain Xaintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy, en la marine; quatriesme Voyage, livre 1 et 2, Paris, Iean Berjon, 1613.

Direction du patrimoine et de la muséologie, Répertoire du patrimoine culturel du Québec, Québec, Ministère de la Culture, des Communications et de la Condition féminine, 2012, site consulté le 29/03/11 [En ligne], www.patrimoine-culturel.gouv.qc.ca

Direction générale des lieux historiques nationaux de Parcs Canada, Liste des désignations d'importance historique nationale (1919-2008), Ottawa.

Jefferys, Charles William, Canada's past in pictures, Toronto, The Ryerson press, 1934, pp. 26-29.

Guitard, Michelle, E. B. Eddy, site industriel, Québec, Ministère de la Culture et des Communications, septembre 1999.

Lapointe, Michelle, « Le syndicat catholique des allumettières de Hull, 1919-1924», Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, 32 (4) mars 1979, pp. 603-628.

Martin, Michael (2006). Working class culture and the development of Hull, Quebec,1800-1929. Ottawa : Bibliothèque et Archives Canada. Collection électronique de BAC.

Taché, Joseph-Charles, Forestiers et voyageurs, Montréal, Fides, 1964 et 1863.

Vincent-Domey, Odette, « L’industrie et le monde du travail », Gaffield, Chad (dir) Histoire de l’Outaouais, Collection Les régions du Québec. Québec : Institut québécois de la recherche sur la culture, 1994, 265-309.

Vincent-Domey, Odette, « Eddy, Ezra Butler ». Dictionnaire biographique du Canada en ligne, 1901-1910, vol XIII, Ottawa, BAC; Québec, Université Laval; Ontario, University of Toronto, 2000.

![Chaudière Falls and Bridge [on the Ottawa river], Henri Fabien,1914](/media/thumbs/7912/300x248-7912_chutes_chaudieres_11E.jpg)