Traditional French Songs in Ontario

par Bénéteau, Marcel

Traditional French songs remain the most dynamic and best-documented aspect of the traditional folklore of Ontario francophones. Not only is the number of songs collected and catalogued by folklorists impressive, but these songs also continue to be a part of family and community gatherings across French-speaking areas of the province. From the choruses sung by the early voyageurs, and then later the lumber jacks, to those heard at contemporary festivals today, traditional songs have always been a reflection of the historical factors that influenced how various areas of the province were settled. These songs, more than any other aspect of the oral tradition, have played a key role in expressing the cultural identity of Franco-Ontarians and form a key part of their collective memory.

Article disponible en français : Chanson traditionnelle française en Ontario

Songs and cultural identity

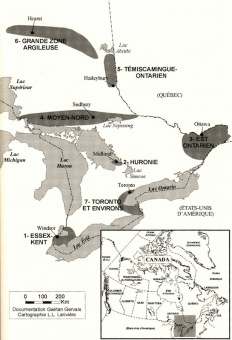

Traditional songs, a well-established part of European culture in New France, accompany the first explorers and voyageurs as they travel across the expanse of Ontario. Later, as the pioneers colonize different parts of the territory, they will take root in what will become the Province of Ontario. The oldest settlement is located in the southwest, around present-day Windsor, and dates back to the founding of the colony of Détroit by the French in 1701. For more than a century, the small population established along the south shore of the Detroit River will remain the only permanent French community on Ontario soil. The descendants of these first settlers—who now live in Windsor and in Essex and Kent counties— maintain distinct cultural traits and linguistic particularities that reflect the long history of their community, which was established so far from the heart of New France.

The second area to be colonized by francophones, starting in the 1830s, is the territory that borders the present-day Province of Quebec. In the beginning, habitant farmers from Lower Canada, mostly French-Canadians, are drawn to the area by jobs in the forest industry. However, they eventually end up crossing the Ottawa River to form farming communities in the united counties of Prescott and Russell, between Ottawa and Montreal. During the same period, other pioneers emigrate from Lower Canada to join the descendants of Métis voyageurs who have established themselves near Penetanguishene, in old Huronia, at the south end of Georgian Bay. Towards the end of the 19th century, another wave of emigration from Quebec will lead to the colonization of the Near North part of Ontario. This group, lured by the prospect of railway and forest industry jobs, and later by opportunities in the mining sector, will settle in communities along the Mattawa–Sudbury–Sault Sainte-Marie axis north of Lake Huron. Towards the middle of the 20th century, francophones take part in the colonization of the Greater North in two other areas—the Ontario side of the Lake Timiskaming District and the “Clay Belt” that stretches from Timmins to Hearst.

Each one of these groups, whose descendants now make up the majority of the Franco-Ontarian population, left the Laurentian Valley at different periods of its political and cultural evolution. Having common roots, those arriving in these various communities bring with them and conserve an oral legacy that reflects the period of their arrival in Ontario, the situations they have to cope with, and the nature of the contacts they maintain with other ethnolinguistic communities. Each group also makes the most of its situation in its own distinctive way. These differences are always present in the oral traditions developed by each group, as are the regional features that add colour to the Franco-Ontarian songbook.

An historical legacy

Researchers have found that the relationship between songs and Franco-Ontarian identity is centuries old. For example, Jean-Pierre Pichette, in his Inventaire ethnologique de l’Ontario français (An Ethnological Inventory of French Ontario), mentions the voyageurs who, during their travels in the Pays d’en haut (the early French name of the territory west of the Ottawa River that is part of Ontario today): “were in the habit of singing to bolster their courage and coordinate their physical efforts”. (Note 1) He underscores the fact that all the 18th and 19th century historical chroniclers and missionaries mention this practice, and those that he makes reference to include: “Gustave de Beaumont who, while passing through Sault-Sainte-Marie in August of 1831, greatly appreciates the ‘charming gaiety’ of the Canadians and the ‘abundance of old French songs’ that they sing while paddling, and concludes that the ‘French character is not easily lost’.” (Note 2)

Pichette also quotes a tourist from France who hears the song Isabeau s’y promène during a train stop in New Ontario (Sudbury area) in 1908: “This melancholic ballad, so sweet, is nevertheless comparable to a victory hymn. The low voice, barely audible in the dead of night, indicates that the French-Canadian race is there, and peacefully conquering the Nipissing.” (Note 3) Germain Lemieux describes how the pioneers settling around the Great Lakes during the New France era would turn to songs for several reasons: “People would sing to remember their childhood, to rid themselves of the sense of isolation, or because they needed to express their joy or their sorrow. The French songs were far from having faded away and would not die; in fact the opposite occurred, since a part of the Medieval and Renaissance repertoire, upon landing on Canadian soil, was enriched by new rhythms and choruses.” (Note 4) In Lemieux’s view, the songs of the voyageurs and the lumberjacks strengthen the ties between the mother country and life in the new land: “Our Franco-Ontarian pioneers faithfully recite the saga of the discoverers, the explorers, and the voyageurs, a saga not learnt from history books, but from the lips of an old man, or of an old friend who was once a voyageur. And it is thus that our voyageur songs, as rugged as the hands of the lumberjacks and log drivers whose stories they tell, immortalized in their particular way the lives and the passing of some of our ancestors.” (Note 5)

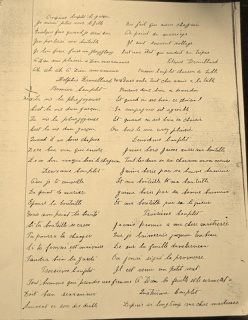

Despite these assertions, first-hand accounts of traditional songs being sung in Ontario communities remain relatively rare until the 20th century. To the examples quoted above, Pichette is only able to add a dozen literary references, including certain generalizations made by Ernest Gagnon and Hubert Larue that “give us good reason to believe that a few of the songs they published were being sung in Ontario.” (Note 6) Tangible evidence of a vast and varied song repertoire dating back to well before the beginning of the 20th century can only be found in the older settlement area of southwestern Ontario (Windsor area). Indeed, several hand-written notebooks, dated between 1895 and 1900, contain hundreds of songs sung by families established in this area as early as the beginning of the 18th century. Some of these notebooks even reveal the names of the singers of each song, making them very valuable ethnological documents. For example, the notebook of farmer Félix Drouillard, which he started in Rivière-aux-Canards in 1897, contains the lyrics to 228 French songs, of which 172 can be traced back to the oral tradition and 56 to published sources (the notebook also contains the lyrics of 47 English songs).

This source identifies some fifty “informants” who allow us to analyze the role the family and its bonds to the community play in the way this repertoire was developed and shared. With the exception of one or two songs, the 172 traditional songs in this notebook are the first evidence of these songs’ presence in Ontario. A good many of them, like La rose blanche, L’hirondelle, Messagère des amours, Le cou de ma bouteille, La bergère aux champs, and Maréchal Biron, among others, are the earliest documented versions of these songs in French North America.

The songs noted by Félix Drouillard—as well as those of ten other scribes living in the southwestern region during the same period—have allowed us to compile the basic traditional song repertoire of French Ontario. What is striking in this repertoire is the surprising rarity of chansons en laisse (commonly known as call-and-response songs), which, in those areas closer to Quebec, make up the bulk of the song repertoire. In the Detroit area—as it is the case among the Acadians, the Métis of the West, and other communities established after the end of the large Québécois diaspora of the 19th century—this type of song plays a minor role, whereas narrative songs with several verses are predominant.

The gathering of folklore material

Ethnologists developed an interest in gathering information in the field during the second decade of the 20th century. The arrival of Marius Barbeau who, in 1911, joined the National Museum staff in Ottawa, marks the beginning of a scientific process for collecting folk material in French Canada. Although most of his research in the field took place in the Gaspé Peninsula, the Charlevoix region, and in the Lower Saint-Lawrence area, Barbeau also collected nearly 200 songs in the Ottawa area between 1916 and 1960. His colleagues, Édouard-Zotique Massicotte and Gustave Lanctôt, gathered 650 additional songs. These researchers focussed their work on the Ottawa area. One of Massicotte’s informants, Honoré Cantin of Hawksbury, solely contributed 169 songs to the Franco-Ontarian repertoire. Lucien Ouellet of the Museum of Civilization deserves a special mention, since he gathered 239 songs in the Ottawa area towards the end of the 20th century.

Northern Ontario—New Ontario—was the second area where research was conducted and, to this day, the largest number of traditional songs have come from there. François-Joseph Brassard, a musician and folklorist from the Saguenay area, pioneered the research in the Kapuskasing and Strickland areas in the 1940s. His main informant, Urbain Petit, sang 465 songs for him. Mr. Petit, originally from Quebec but a migrant to Strickland at age 53, had learned nearly his entire repertoire in his home province. For him and other migrants of his generation, these songs no doubt helped them maintain ties to their province of origin. Through them this traditional culture took root in a new territory.

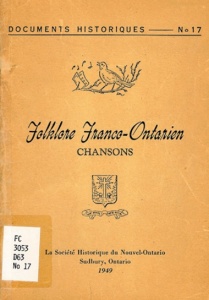

For Northern Ontario the most notable researcher is clearly Father Germain Lemieux, SJ. Born in Cap Chat, in the Gaspé Peninsula in 1914, Germain Lemieux arrived in Sudbury in 1941 to teach at the Collège du Sacré-Cœur [a private Catholic French-language high school]. In 1948, the Société historique du Nouvel Ontario (New Ontario Historical Society) asked him to interview some of the “Franco-Ontarian pioneers” around Sudbury to determine “to what extent they were still French at heart.” (Note 7) These conversations yielded encouraging results, which proved to be the starting point for his long career as a folklorist. Although better known for his work collecting and analyzing folk tales, (Note 8) between 1948 and 1980 Germain Lemieux also amassed and archived a significant collection of songs, some 2,000 versions of 735 traditional songs gathered in the Near North from Mattawa to Sault Sainte-Marie. Father Lemieux never published his collection, so it remains for the most part unpublished and unknown, with the exception of four small songbooks showcasing approximately 150 songs. (Note 9) A summary study published in 1964 (Chanteurs franco-ontariens et leurs chansons) [Franco-Ontarian singers and their songs] briefly analyzes the form and content of this repertoire. (Note 10) A cassette recording, Ce qu’ils m’ont chanté (What they sang for me) also offers a very small sample of this monumental collection.

There is one more significant source of material for Northern Ontario. Since 1981, the département de folklore et d’ethnologie de l’Université de Sudbury (DFEUS) [Department of Folklore and Ethnology at the University of Sudbury, a part of Laurentian University] has been archiving the research material gathered by its students. Begun in 1981 by Jean-Pierre Pichette, this fonds now holds some 2,000 research enquiries dealing with a variety of subjects, including approximately 8,000 traditional songs. The vast majority of the latter come from Northern Ontario and can be considered an extension of Germain Lemieux’s research. More than any other collection, it gives an accurate picture of the current Franco-Ontarian repertoire. The songs of this tradition are still very much alive, even if the repertoire’s diversity has diminished over time. There has been an increase in the number of call-and-response songs, while narrative songs in verse and those in the form of a dialogue have completely disappeared.

Lastly, there is the research conducted by the author of this article in the southwestern region of the province, around Detroit. Between 1990 and 2001, approximately 1,700 versions of some 645 traditional songs were gathered and classified (these include the songs found in Félix Drouillard’s notebook). The three collections mentioned above—Lemieux, Bénéteau and that of the DFEUS—in total contain 11,000 versions of 1,500 songs that have been collected in Ontario.

The ongoing classification and digitization of these collections at the University of Sudbury is an important step towards gaining a better understanding of this vast repertoire and making it more accessible. Given the impressive number of songs, a thorough analysis is needed to view the material in a global and coherent manner. Since much of the Franco-Ontarian population has its roots in Quebec, it has sometimes been difficult to isolate the specific characteristics of the Franco-Ontarian repertoire. To quote Pichette: “The same can be said of the songs of Franco-Ontarians as it is sometimes said of their literature, and even of the community itself: they are so similar to the Québécois tradition that they go unnoticed in the eyes of one who reads them in a Quebec songbook.” (Note 11) Germain Lemieux sums up the value of the Sudbury area for research purposes as follows: “The group of French-Canadians in the Sudbury area form a microcosm of the numerous centres of traditional culture of Quebec and Acadia…” (Note 12) The classification of the three major collections gathered in Ontario has made it possible to grasp the specific nature of this repertoire. The work of the first folklorists who studied the areas bordering the Province of Quebec clearly documents this territorial “extension” of the source culture. However, the more recent research reveals the dynamic nature of this repertoire as well as its evolution and specific regional characteristics. The Bénéteau collection, for example, gives us a historic base specific to the Province of Ontario. The Lemieux-Brassard-Bourassa collections document the way a population from Quebec establishes itself in a new territory and also what it chooses to conserve and celebrate. Lastly, the DFEUS collection illustrates how a traditional repertoire evolves in the face of multiculturalism and new media. Examined together, these collections give us a picture of an emerging Franco-Ontarian identity based on a cultural heritage that is constantly evolving.

The role of artists

Relatively few musicians have taken advantage of the treasure trove of traditional French songs in Ontario. Despite the significant role of traditional songs in social and family life, as well as their contribution to creating a sense of identity in the Franco-Ontarian community, generally speaking the francophone population has been reticent to showcase them in its art and culture. Although it is deemed perfectly normal to celebrate our roots in the family context, the acceptance of this type of artistic expression in the public sphere, except during the Christmas season, has been a slow process.

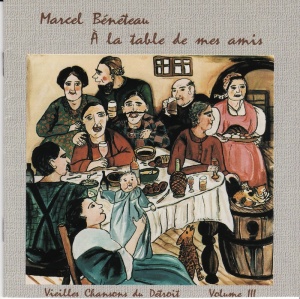

In recent years, a number of folklorists and singer–songwriters working to change this attitude have achieved encouraging results. However, Ontario has yet to experience the same “trad” wave that has swept the Quebec music scene. That being said, Garolou, one of the first bands to achieve a high level of success by singing traditional songs in the 1970s—in Quebec as well as across French Canada—was formed by the brothers Michel and Bobby Lalonde from eastern Ontario. Their progressive rock arrangements produced several hit songs, such as Victoria, Ah toi, belle hirondelle, Germaine, and La belle Françoise. Nevertheless, their groundbreaking achievements spawned few others. In the ensuing decade, Donald Poliquin, originally from Hearst, produced two traditional music albums: Poliquin (1982) and Ziguedon (1987). In the 1990s, Marcel Bénéteau issued three CDs entitled Vieilles chansons du Détroit (1992-2000) [Old songs from the Detroit area] featuring 60 songs from southwestern Ontario. This initiative did inspire some artists, since a dozen bands in Quebec and France (Les Chauffeurs à pied, Entourloube, Vent d’arrière, and Cabestan, to name a few) recorded versions of some of these songs from southwestern Ontario.

In the last decade, the traditional music scene has undergone a revival, particularly in eastern Ontario. In the Ottawa area, the band Deux Saisons achieved international success before leaving the music scene in 2004. Since 2007, this band, partly reunited by singer Louis Racine of Casselman, has been performing here and there under the name La ligue du bonheur. The band Swing, also from eastern Ontario, made the pop charts several times by reviving traditional songs through a fusion of traditional music and hip-hop, with albums bearing amusing double-entendre titles like La chanson s@crée [The s@cred and swearing song] and Tradarnac [a combination of the word “tradition” with the common French-Canadian swear word Tabernac]. In Sudbury, the band Les Cokrels also produced an energetic compilation album called Rocklore…

The Future

Let us hope that the recent efforts to draw attention to the traditional Franco-Ontarian song repertoire will inspire new generations of musicians to take a fresh look at this inexhaustible fountain of inspiration. The current digitization of the archives of the University of Sudbury and the Centre franco-ontarien de folklore [Franco-Ontarian Folklore Centre], which will include the songs of the Germain Lemieux collection, will make it much easier for artists, researchers and members of the public all over the French-speaking world to consult this repertoire. Now that this heritage has been saved, there remains the task of making it widely available and promoting its significance.

Marcel Bénéteau

Head of the Ethnology and Folklore Department

University of Sudbury

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Canoe Manned by Voyag

Canoe Manned by Voyag

eurs Passing a ... -

CD cover from Marcel

CD cover from Marcel

Bénéteau’s “A l... -

Collection of Franco-

Collection of Franco-

Ontarian folk s... -

Compilation CD of the

Compilation CD of the

group “Les Cok...

-

Father Germain Lemieu

Father Germain Lemieu

x, S.J. -

Francophone Regions o

Francophone Regions o

f Ontario -

Louis Racine, représe

Louis Racine, représe

ntant de la scè... -

Numéro spécial de la

Numéro spécial de la

revue Canadien ...

-

Page from Felix Droui

Page from Felix Droui

llard’s manuscr... -

Pochette du CD «À la

Pochette du CD «À la

table de mes am... -

Promotion de la tourn

Promotion de la tourn

ée «La Grande V... -

Recueil de chansons t

Recueil de chansons t

raditionnelles ...

Documents sonores

- Ah toi, belle hirondelle

-

Aux Illinois

Interpreter : Garolou.

Writer : Traditionnel.

Album : Tableaux d’hier, vol. 2, 1978.

Aux Illinois

Interpreter : Garolou.

Writer : Traditionnel.

Album : Tableaux d’hier, vol. 2, 1978.

- Beau marinier

- Captation ethnologique de Beau marinier

Catégories

Notes

1. Jean-Pierre Pichette, Répertoire ethnologique de l’Ontario français. Guide bibliographique et inventaire archivistique du folklore franco-ontarien, Ottawa, les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1992, p. 21, (our translation).

4. Germain Lemieux, Chanteurs franco-ontariens et leurs chansons, Sudbury, La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques nos 44-45, 1964, p. 20, (our translation).

7. Germain Lemieux, « Mon projet cinquante ans plus tard », in Jean-Pierre Pichette (dir.).L’œuvre de Germain Lemieux, s.j. Bilan de l’ethnologie en Ontario français. Actes du colloque tenu à l’université de Sudbury les 31 octobre, 1er et 2 novembre 1991, Sudbury, Prise de Parole and the Centre franco-ontarien de folklore, p. 29, (our translation).

8. See Germain Lemieux, Les Vieux m’ont conté, vol. 1 – 33, Montréal, Éditions Bellarmin, 1973-1993.

9. Germain Lemieux, Chansonnier franco-ontarien I et II, Sudbury, La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques 64, 1974) and Documents historiques no. 66, 1975; see also Folklore franco-ontarien : chansons I et II, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques 17, 1949 and Documents historiques 20, 1950.

10. Germain Lemieux, Chanteurs franco-ontariens et leurs chansons, Sudbury, La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques nos 44-45, 1964, p. 20.

Bibliographie

Jean-Pierre Pichette, Répertoire ethnologique de l’Ontario français. Guide bibliographique et inventaire archivistique du folklore franco-ontarien, Ottawa, les Presses de l’Université d’Ottawa, 1992, p. 21.

Germain Lemieux, Chanteurs franco-ontariens et leurs chansons, Sudbury, La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques nos 44-45, 1964, p. 20.

Germain Lemieux, « Mon projet cinquante ans plus tard », dans Jean-Pierre Pichette (dir.). L’œuvre de Germain Lemieux, s.j. Bilan de l’ethnologie en Ontario français. Actes du colloque tenu à l’université de Sudbury les 31 octobre, 1er et 2 novembre 1991, Sudbury, Prise de Parole et Centre franco-ontarien de folklore, p. 29.

Germain Lemieux, Les Vieux m’ont conté, vol. 1 – 33, Montréal, Éditions Bellarmin, 1973-1993.

Germain Lemieux, Chansonnier franco-ontarien I et II, Sudbury, La Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques 64, 1974) et Documents historiques no 66, 1975; voir aussi Folklore franco-ontarien : chansons I et II, Sudbury, Société historique du Nouvel-Ontario, Documents historiques 17, 1949 et Documents historiques 20, 1950.