Alexis de Tocqueville’s visit to Lower Canada in 1831

par Corbo, Claude

In Alexis de Tocqueville's works, many pages are dedicated to the inhabitants, their historic destiny, as well as to the cultural and political situation of Lower Canada within the British Empire. His writings offer acute observations and penetrating analyses on the topics listed above. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805-1859) is notably famous for his masterpiece Democracy in America (1835), which offers a brilliant analysis of the inevitable advent of the young United States of America's democratic society. In this work, Tocqueville examines with care, a civilisation characterised by a desire for equality, a sometimes fanatical individualism and the ever looming tyranny of the majority. The work is based on meticulous observations, accumulated during a nine-month journey across the country (from May 9th, 1831 to February 20th, 1832) with a colleague, the magistrate, Gustave de Beaumont. It is less widely known that the two travellers also visited Lower Canada from August 23th to September 2nd, 1831, as Tocqueville did not write any specific works as a result of that particular voyage.

Article disponible en français : Alexis de Tocqueville et le Bas-Canada en 1831

LowerCanada in 1831

Already a British colony for about 75 years, in 1831, Lower Canada's population was predominantly French speaking, catholic and rural. A fifth of the total population of 550,000 inhabitants was of British origins. Agriculture, exploitation of natural resources and trade were at the heart ofthe economy. The Catholic Church, whose leaders had already adjusted themselves well to the British Empire's domination of the colony, had taken to looking after the population, the work divided among its many parishes. A small secular bourgeoisie (a middle class largely composed of free-lance professions, businessmen, a few teachers and journalists), intrigued by Europe's liberal ideas and by the political experience of the United States, had become actively involved in their own brand of politics since the election of the first legislative assembly in 1791. At the time of Tocqueville's visits, political tensions had been building in Lower Canada and would culminate in the armed rebellion of 1837-1838 (the Patriots' War). The Legislative Assembly (House of Representatives), composed mainly of French Canadian representatives, lead by Louis-Joseph Papineau, was often at odds with the British Governor and his Legislative Council (the Governor appointed members of the Council, who were mostly British). The colony's budget was one of the main sources of disagreement, for the Assembly demanded that they have control of it, while the governor sought to keep this power for himself alone. Louis-Joseph Papineau's Canadian Party had been seeking to establish its nationalist claims-the colony's internal autonomy-aswell as its liberal agenda-true power for the Legislative Assembly. It was to such a country that Tocqueville had come.

Toqueville's Visit and the Encounters that Resulted

Tocqueville and Beaumont's stay in Lower Canada (NOTE 1) appears to be somewhat of a spontaneous short pause in his plans to thoroughly explore the United States. In a letter to his mother, dated June 19th,1831 (that makes it more than two months after he had arrived in the States) Tocqueville writes that he wishes to "make the trip that is quite the fashion around here" and travel to the Niagara region. He goes on saying: "Canada raises our curiosity. The French nation has been preserved there. As a result, one can observe the customs and the language spoken during Louis XIV's reign (NOTE 2). In a letter dated September 7th, 1831, after his stay in Lower Canada, Tocqueville writes how happy he was with his decision to visit: "not even six months ago, I believed, like everyone else, that Canada had become thoroughly English". It was a discovery he fully appreciated, but that still left him a little perplexed: "We felt like we were at home and everywhere people greeted us as one of their own, as descendants of "Old France" as they called it. But to me, it seems more like Old France lives on in Canada and that it is our country [France] which is the new one (NOTE 3)." Thus, Tocqueville was surprised by realties he discovered in Canada. Compared to his visits to other foreign countries, the visit to Lower Canada was a brief one (NOTE 4). Fortunately, it is his perspicacity, his clear-sightedness and his remarkable wisdom that make up for the shortness of his visit.

It is also interesting to note the kinds of people Tocqueville met and talked to. He spent time exchanging with farmers (when travelling around Quebec City), clergymen (who, he says, constitute "the highest social class among Canadians") and lawyers (during his visit of a courthouse). He also saw those who were still called "Indians". The elite left him thoughtful; he believe dthat among the "enlightened classes" there was already the temptation of letting themselves be assimilated by the English; for "many [...] of them did not seem as eager as we would have thought to preserve some part of their origins, thereby becoming a distinct people. To us, it seemed many were not far from letting themselves be willingly assimilated by the English (NOTE 5).

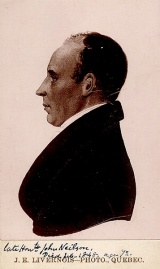

Tocqueville also had meaningful and rich exchanges with the notable public figures. However, the selection of notable individuals that he met with and cited is limited. He states that the French Sulpician Joseph-Vincent Quiblier, Superior of the Grand Séminaire (who arrived in Canada in 1825) that he met in Montreal on August 24th, "is a cautious and conservative-minded man, quick to accommodate the powers that be." According to him, the Mondelet brothers "are moderate reformists." John Neilson, a Scottsman who arrived in 1790 and editor of the bilingual newspaper The Quebec Gazette, as well as representative in the House of Assembly, "went to London in 1823 and 1828 to present petitions in protest against the union of the two Canadas." Neilson had shared common ideas with Louis-Joseph Papineau; but, at the time Tocqueville visited, Neilson and Papineau saw things differently and gradually grew apart. Tocqueville and Beaumont did not seem to meet anyone with more radical political positions. There are, in fact, no documents mentioning that Tocqueville would have met Papineau during his stay. Neither did he meet with members of the government of the public administration of Lower Canada.

Tocqueville's Views on Lower Canada

For Tocqueville, Lower Canada was a discovery and a revelation that proved to be both moving and painful.

Just as many other European travellers, Tocqueville loved the majestic landscapes, such as that of the breathtaking Saint Laurence River. The country is, in itself, picturesque and majestic. Nonetheless, he was concerned with the fate of the Natives, both in Lower Canada and in the United States. He expects that, for the aboriginal peoples, not much good will come out of the occupation of the lands by whites. His discovery of a French-speaking people both surprised and delighted him. He noticed the demographic growth of the French Canadians, their numbers almost ten times what it was when the colony was handed over to Great Britain. But on certain occasions, he mostly remarks gladly that there is still a part of France living in North America, a strong and vigorous people that is aware of and close to its roots-even after three quarters of a century of British rule! French Canadians have kept their time-honoured cultural traditions alive. In a letter dated September 7th, 1831, hed escribes his hosts: "They are still French to the core; not only the elderly, butall of them, even the little toddler who spins his top."(NOTE 6) Canada's French-speaking population "still remain very much like their Old French cousins".

He also notices that the French Canadians are a warm, welcoming people always joyful; they are high-spirited and witty. In the countryside thrives a well-organised and properly housed peasantry. The villages are beautiful and the country looks very much like the "Old France". The seigneurial system, which would last until 1854, is more of a formality than anything else, even though it is a source of irritation for some. But this does not keep the lands from being properly farmed or from prospering. Religion is central to the community; the clergy holds an important place and proves to be unquestionably loyal to the British authority. But, for Tocqueville, religion seems to be a phenomenon built on a sincere faith, as well as an important part of their identity, although it is something that should have little to do with politics. Religion is, however, also an obstacle to mixed marriages. Most certainly, Tocqueville is deeply moved and happy to find a French speaking population in Lower Canada; a people that is deeply rooted in its traditions and identity, whose population is rapidly growing and that seems determined-despite a political conscience that does not express itself too loudly-to remain true to itself.

But the joy of the rediscovery, the reunion with a too long lost French-speaking people, is quickly tarnished and even overshadowed by worries. The French Canadians are obviously a conquered and subdued people. Even though the peasants are prosperous, the real wealth is in the hands of the country's Englishmen. The Mondelet brothers, who Tocqueville met in Montreal on August 24th, as well as the anonymous English merchant he met on August 26th, reveal to Tocqueville that, "almost all the wealth and commerce is under English control". On September 1st, Tocqueville confirms in his notes that "the English have control of all foreign trade and run domestic trade without any opposition(NOTE 7)". A conversation with an anonymous merchant from Quebec City confirms that the English sector of the population, a minority, was very confident about its future. The domination of French Canadians is noticeable when one observes the very different situations governing the country's two spoken languages. In Montreal, as well as in Quebec City, the English language dominates public life and the marketplace: "The majority of the newspapers, ads and even the commercial signs of French-speaking shopkeepers are in English." In both cities, "all the signs are in English and there are only two English theatres". During his visit to the courthouse in Quebec City, Tocqueville observes the predominance of the English language and the mediocrity of the language of French-speaking lawyers, which is riddled with Anglicisms (NOTE 8). The majority of newspapers are also mostly in English. In these conditions, one cannot be too surprised that Tocqueville worried that the "enlightened classes" seemed interested to "merge with the English".

On the basis of these observations he concludes bluntly: "it is easy to see that the French Canadians are a conquered people (NOTE 9)." For Tocqueville, Lower Canada's future is uncertain. Some elements do seem encouraging: the people's strong sense of identity, the peasantry's healthy economy and spirits, the development of the school system, the sheer number of people. But the French Canadians and their culture still seem to face many dangers.

Tocqueville tried to envision the future of the French-Canadian people, but his ideas remained hesitant and groping. However, it seems as though he was able to foresee the hardships that were destined to befall not only the French-speaking people of Lower Canada who would eventually become Quebeckers, but also the rest of the peoples living across the North American continent. As he evaluates the future of Lower Canada during his visit there, as well as years later, notably in 1833 and in 1837, Tocqueville willingly puts the blame on the lack of energy France put into its colonisation endeavours in New France. In a letter dated November 26th, 1831, he criticises France's dealings with its North American colony during the 18th century, referring to the"abandonment" of loyal subjects of the French Empire. Then he adds that it was"one of the greatest ignominies of Louis XV's shameful reign".

Although his discovery of Lower Canada had brought him much joy, after visiting the courthouse in Quebec City on August 26th, 1831, Tocqueville would make a statement that he would never go back on. It is a statement that many nations and peoples, Quebec among them, have begun to appreciate since: "I have never been more convinced than after I left the courthouse that the greatest and most irreversible tragedy for a people is to be conquered (NOTE 10)." OnAugust 29th, he wrote that he believed the people might "awaken": nonetheless all would be lost if the upper classes didn't shoulder the irresponsibilities, instead of letting themselves being swallowed by the "trend to assimilate into English society". Three months later, on November 26th, his concerns for the future of North America and Lower Canada's French-speaking populations reasserted themselves: "I have just seen in Canada, a million brave and intelligent French people that are fit to one day form the basis of great French-speaking nation in North America, but who now live as strangers in their own country. The conquerors have a firm hold on commerce, jobs, wealth and power. They form the upper classes, dominating the entire society. In every locality where the French Canadians do not have the upper hand in terms of their sheer strength in numbers, the dominated people is gradually losing its culture, its language and its national identity. (NOTE 11)

Even though the French Canadian elite did not "merge with the English", as Tocqueville had feared, but rather, many members of that same elite began (around the middle of the 19th century) the fight to promote and develop French-speaking culture, Alexis de Tocqueville's observations on Lower Canada and the French speaking population of North America are still relevant. His works on Lower Canada were not largely available before the publication of the 5th volume of his complete works in 1957. The first publication in Quebec became available in 1973. Later (but before the author's edition published in 2003; see bibliography), only partial publications were printed. Nevertheless, Tocqueville's writings have captured the attention of several political commentators, including political experts Stéphane Dion and Gérard Bergeron, who have written reading commentaries that offer comparisons between Tocquevilles's works and Quebec's evolution over the last half century. Tocqueville's views on the hardship of being a French speaker in North America still offer material for reflection. Thus the rediscovery of his writings on the matter is a positive recent development that is ever increasingly captivating the interest of many.

ClaudeCorbo

Faculty of political science

Université du Québec à Montréal

NOTES

Note 1: After leaving Buffalo (N.Y) by boat on August 20th, 1831,Tocqueville and Beaumont arrived in Montreal on the 23rd of August and left on the evening of the 24th. The steamship John-Molson left them in Quebec City on the evening of the 25th. They stayed in Quebec City until August 31st; they visited the city, met various people of influence, visited a "reading room", as well as a civil court. Excursions allowed them to discover various countryside villages surrounding Quebec City: they stopped in Ancienne-Lorette on August 28th, Beauport on the 29th (although Beaumont wrote it was on the 28th), as well as communities on the south bank of the St. Laurence River as far as Saint-Thomas-de-Montmagnyon the 31st. On the same day, they sailed back to Montreal aboard the Richelieu, after which they left Lower Canada on September 2nd and headed for Albany (N.Y) and then Boston.

Note 2: Alexis de Tocqueville, Correspondance familiale, Œuvres complètes, t. XIV, Paris, Gallimard, 1998, p. 105.

Note 3: Ibid., p. 129. To his sister-in-law Émilie, on the same day, Tocqueville tells her that she would find in Lower Canada's "people very similar to her beloved people from Lower Normandy", ibid., p. 132.

Note 4: Thus in comparison, Tocqueville visited Italy and Sicily for four month, from December 1826 to April 1827, as well as England and Ireland from the end of April to the end of August 1835.

Note 5: Alexis de Tocqueville, Œuvres, Paris, Gallimard, « Bibliothèque de la Pléiade », t. I, p. 209.

Note 6: Alexis de Tocqueville, Correspondance Familiale, p. 130.

Note 7: Alexis de Tocqueville, Œuvres 1, p. 210.

Note 8: Ibid., p. 202, 203, 204.

Note 9: Ibid., p. 202.

Note 10: Alexis de Tocqueville, Œuvres I, p. 205.

Note 11: Alexis de Tocqueville, Correspondance Familiale, p. 146.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alexis de Tocqueville'sworks

Tocqueville, Alexis de, Œuvres complètes : œuvres, papiers et correspondances, édition définitive publiée sous la direction de J.P. Mayer, Paris, Gallimard, 1951-2002, 18 tomes en 30 volumes.

Tocqueville, Alexis de, Œuvres, Paris, Gallimard, (three volumes published to date), à compter de 1991. (Coll.« Bibliothèque de la Pléiade ».)

Tocqueville, Alexis de, Lettres choisies. Souvenirs 1814-1859, Paris, Gallimard, 2005. (Coll. « Quarto ».)

- In addition, there are several pocket editions of Démocratie en Amérique.

Tocqueville's writingson Lower Canada

Tocqueville au Bas-Canada, textes présentés par Jacques Vallée, Montréal, Éditions du Jour, 1973, 185 p.

Regards sur le Bas-Canada, choix de textes et présentation de Claude Corbo, Montréal, Typo, 2003, 326 p.

- A few pages by Tocqueville on Lower Canada have also been reproduced in the following written works:

Hébert, Robert, L'Amérique francophone devant l'opinion étrangère 1756-1960. Anthologie, Montréal,L'Hexagone, 1989, p. 97-101.

Bureau, Luc, Pays et mensonges. Le Québec sous la plume d'écrivains et de penseurs étrangers, Montréal, Boréal, 1999, p. 351-363.

Studies on Tocqueville andLower Canada:

Bergeron, Gérard, Quand Tocqueville et Siegfried nous observaient..., Sillery, Québec, Presses de l'Université du Québec, 1990.

Dion, Stéphane, « La pensée de Tocqueville. L'épreuve du Canada français », Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, vol. 41, no 4, 1988, p. 537-552.

Langlois, Simon, « Alexis de Tocqueville, un sociologue au Bas-Canada », La Revue Tocqueville/The Tocqueville review, vol. XXVII , no 2, 2006, p. 553-574.

Leclercq, Jean-Michel, « Alexis de Tocqueville au Canada (du 24 août au 2 septembre 1831) », Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française, vol. 22, no 3, 1968, p. 343-364. (Cet article est tiré d'un mémoire présenté à l'Université de Lille en 1965 pour l'obtention d'un diplôme d'études supérieures en sciences politiques intitulé Les études canadiennes d'Alexisde Tocqueville.)

- Those seeking more information on Tocqueville and Beaumont's voyage to the United States might find Wilson Pierson's very knowledgeable study on the matter very helpful: Tocqueville and Beaumont in America, New York, Oxford University Press, 1938, or the abridged version published by Dudley C. Lunt, with the consent of the author: Tocqueville in America, Garden City (N.Y.), Double day, 1959.

- There are also short anlyses of Tocqueville's ideas on Lower Canada available, particularly in Heinz Weinmann, Du Canada au Québec: généalogie d'une histoire, Montréal, L'Hexagone, 1987, p. 225-235, and in Armand Yon, Le Canada français vu de France, Québec, Presses de l'Université Laval, 1975, p. 13-15.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Champs de mars Montré

Champs de mars Montré

al 1830 -

De Tocqueville

De Tocqueville

-

Deux habitants, avec

Deux habitants, avec

cheval et traîn... -

Jean-Marie Mondelet

Jean-Marie Mondelet

Documents PDF

-

Extrait de la conversation de Tocqueville avec Mr. Neilson

Extrait de la conversation de Tocqueville avec Mr. Neilson

-

Extrait des écrits de Tocqueville où il décrit le Bas-Canada

Extrait des écrits de Tocqueville où il décrit le Bas-Canada

![Papineau s'adressant à une foule [Papineau addressing a crowd], BAC.](/media/thumbs/239/200x0-19_Papineau.jpg)

![Vue de Québec à partir de la pointe Lévis [Quebec City as Seen from the Pointe de Lévis] (Quebec City) 1832. BAC](/media/thumbs/1177/300x0-19_Que__bec_1832.jpg)

![La ville de Montréal, vue de l'ouest [the City of Montreal, as seen from the west] (Quebec City). BAC.](/media/thumbs/1449/300x0-19_Montre__al_vue_agriculture.jpg)

![Henri Beau. Sulpicien [Suplician], Late 18th Century. BAC](/media/thumbs/1175/170x0-19_sulpicien.jpg)

![Unknown Artist, Indien et Habitant avec Traîneau [Indian and inhabitant with a Tobogan] (Quebec City) around 1840. BAC](/media/thumbs/1338/300x0-19_Indien_et_habitant_1838.jpg)

![Le Marché de la Haute-Ville, la Basilique et le Séminaire en Hiver [The Upper Town Market, the Basilica and the Seminary in Winter] (Quebec City). BAC.](/media/thumbs/1454/310x0-19_Marche___Que__bec_c1830.jpg)