Coverdale Collection

par Hamel, Nathalie

With multiple thousands of objects, the Coverdale Collection is one of the most important in the history of heritage conservation. Assembled from 1928 to 1949 by William H. Coverdale, president of Canada Steamship Lines, the colossal collection includes ethnographical and archaeological items, as well as some very old images. The collection is primarily known for its portrayal of Canadian history and the traditional French-Canadian way of life.

Article disponible en français : Collection Coverdale

The Collection

Today, the Coverdale Collection has been integrated into Canada and Quebec's national collections. Furthermore, the collection's objects have been distributed for conservation at several institutions. The 2,500 French-Canadian and the 800 Native American ethnographic items are kept in Quebec City's Musée de la Civilisation, while 300 works of art have been secured in the reserves of the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec. Approximately 2,400 images [photos, paintings, etc] depicting the Canadian history have been given into the care of the National Archives of Canada and around sixty works of art can now be found in the National Gallery of Canada. A complete overview of the collection, also includes a mention of the archaeological items now integrated with the Province of Quebec's collections, as well as a few items offered to various other museums during the 1950s. The vast array of objects in the Coverdale Collection have frequently been used in the exhibition activities of the organisations that have been entrusted with the various items of the collection.

Widely renowned among experts, the Coverdale Collection was, for a few decades, considered to be the collection that offered the most accurate depiction of Canadian, Quebec and Native cultural identity. Today, the collection's parallel (and somewhat dual) cultural identity (Canada-Quebec), as well as some of the occasional key pieces of information gathered by W.H. Coverdale, while purchasing the items, have caused many experts to call into question the representativeness of the whole.

The Early Stages of the Collection: Images from Canadian History

No one knows exactly when William H. Coverdale became a collector, but he most likely started collecting before taking the position of president at Canada Steamship Lines in 1922. The company owned the Manoir Richelieu hotel. After it burnt down, in 1928, the president saw an opportunity to give free rein to his passion of collecting. The new hotel, inaugurated in June of 1929, was built in an architectural style that took its inspiration from French castles. The company however presented it as either being inspired by the architecture of Cardinal de Richelieu's era, the style of the French monasteries or that it was meant to be suggestive of the imposing mansion of a noble. The interior decoration and furniture evoked the tastes of New France's aristocracy and was in keeping with the building's the architectural style (NOTE1).The new hotel sought not only to follow current trends in the hospitality business, but also that of American collectors who at the time were attemptingto recreate the atmosphere of the French chateau in their residences. For them it was important to establish harmony among their choices of architecture, furniture, paintings, woodwork and fabrics (NOTE 2).

Desirous of adding an original finishing touch to the interior design of the Manoir Richelieu, Canada Steamship Lines' president began to build up a collection of works illustrating Canadian history, from the beginning of French rule to the Confederation, in 1867. At the time William H. Coverdale was one of the first collectors interested in such items. Thus, he was able to merge the company's commercial objectives with his personal passion, which are two goals that would quickly become intertwined.

Above and beyond interior decorating, the company had an additional purpose for collecting, something nobler that demonstrated their determination to leave a cultural legacy. In fact, the collection's main purpose was to preserve and to pass on a legacy of cultural heritage,"not only for the pleasure and edification of people of our own times, but also for those who, in generations to come, will inherit a deep reverence for the rich and colourful story of the Dominion of Canada (NOTE 3).

By the early 1940s, the collection consisted of about 3,000 works and William H. Coverdale thought it to be almost complete. As a result, he decided to undertake a new project: purchasing furniture and French-Canadian antiques that would be used to furnish the company's other hotel, the Hôtel Tadoussac.

A Collection of French-Canadian Antiques

Built in 1868, the Hôtel Tadoussac was in such a bad state that the company had to demolish it in 1941, in order to replace it with a new building. It was at that time that William H. Coverdale came up with an original interior design idea: with this hotel, he would use local antiques as the fundamental elements for furnishing the hotel's public spaces. In only a few months, with the help of May Cole, a curator hired by the company, he collected almost 350 items. The furniture and antiques, as well as the traditional trades and crafts from Charlevoix used to build and decorate the hotel lent its unique character to the place, creating a style that the company would come to call the "habitant style". The collection would include about 350 pieces of furniture, as well as a few hundreds artisan pieces in ceramic, pewter, as well as artisan tools, etc.

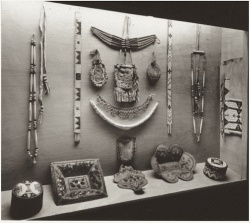

The construction of the new Hôtel Tadoussac was also an occasion to search the surrounding grounds and to dig to uncover the ruins New France's first trading post. Pierre Chauvin once erecte da building in Tadoussac in 1599. He had apparently built it on land that would later become the property of Canada Steamship Lines. Foundations of a structure were indeed found on site and a replica of the Chauvin trading post was built to house an "Indian Museum". Starting in the summer of 1942, the site's exhibit included ethnological and archaeological artefacts, which were intended to be proof of contact between Europeans and Native peoples.

A Renowned Collection

Between 1928 and 1949, the various parts of the collection amassed by Coverdale were not only included in the on-site displays for which they were originally compiled, but they were also presented to the general public as a part of about twenty travelling exhibits. Many catalogues of the Manoir Richelieu Collection were published and widely distributed. The large quantity of catalogues distributed made it possible to promote the collection in Canada and in the United States, as much to the clients of Canada Steamship Lines as to the experts collectors of Canadiana.

As a result of such increased visibility and no doubt to the quality and originality of the pieces, the Coverdale Collection's reputation continued to grow. Consequently, when the company announced that it was discontinuing its cruise services in November of 1965, even though it would still continue to run its hotels, the future of the now famous collection seemed uncertain. Would it be scattered among various museums, divided up by an auction or bought by American collectors? Would Quebec risk losing such a treasure? Immediately, Quebec's Ministère des Affaires Culturelles [Cultural Affairs Ministry] began to take interest in acquiring the Coverdale Collection. At a time when the Ministry was considering building the Museum of Man, the collection seemed to be a rare opportunity.

Announcement of the definitives hutdown of the Hôtel Tadoussac, at the end of the 1966 summer tourist season, renewed concerns about the future of the collection. There were also various rumours going around about the possibility that Canada Steamship Lines might donate some items to Ontario Museums. Quebec's fear of possibly losing of the Coverdale Collection to Ontario greatly resembled its later concern about losing Quebec's cultural heritage to the predominant American or Ontarian majority; such recurring fears had been a preoccupation among Quebeckers since the beginning of the 20thcentury (NOTE4). It was at a time when a growing nationalist movement tended to favour initiatives that would preserve and promote Quebec's French roots and cultural heritage. And so the rumours concerning the Coverdale Collection influenced the concerned authorities to take steps to ensure that the collection's traditional French Canadian items would remain in the province of Quebec.

The Collection Becomes an Official Part of Quebec's National Heritage

And so, in 1968, the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles finally became the owner of Hôtel Tadoussac's Euro-Quebec and Native ethnological collections that once had been a part of the archaeological collection on display in the Chauvin trading post exhibit. Experts from the ministry appraised the total value of the collections and recommended that it be purchased for a total sum of $255,000. Their assessment stated that: "All these collections form a rare and priceless treasure which should be purchased by the government of Quebec. It is a unique occasion - and probably the last - to acquire such a complete selection of artefacts representing Native and Quebec civilisations [sic] (NOTE 5)."

This acquisition was seen to be "a nact of historical significance towards preserving and protecting Quebec's cultural heritage" (NOTE 6) since it substantially increased the quantity of ethnographical artefacts in the Musée du Québec's national collection.

In the late 1960s, the politicalcontext in Quebec's was an opportune time to officially designate the Coverdale Collection as an integral part of Quebec's official cultural heritage. During the Quiet Revolution, numerous nationalist activities of great portent took place; Jean Lesage's Liberal government passed series of reforms that had two main objectives in mind: accelerating the modernisation of Quebec society, which would be based on the Social Welfare State, and promoting the cultural (and possibly national) identity of French-speaking Quebeckers (NOTE 7). It is in this context, that in 1961, the Ministère des Affaires Culturelles was establish; it was intended to be "a sort of Ministry of the French-Canadian Civilisation(NOTE 8)".

Major Changes: the Creation of a New Museum

The purchase of the Coverdale Collection, with its 2,500 ethnographical objects and just as many archaeological items, doubled the number of ethnographical items that had been acquired by the Musée du Québec over the previous forty years (NOTE9). As a result, the institution faced a dire shortage of space in which to store and exhibit the collections.

The recent (substantial) growth of the collections required that the museum be expanded, a necessity that had already been formally requested for some time. As a result, controversies as tothe optimal solution for creating new exhibit space, as well as to the focus of the newly expanded museum ensued. After years of debate, the powers that be agreed that the solution would be to divide the collections into two parts and create two different museums: an art museum (the Musée du Québec, which would later (in 2002) be renamed the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec) and the Musée de la Civilisation. The Coverdale Collection was divided between the two institutions. About 300 works of art remained in the Musée du Québec while the ethnographical collections were transferred to the Musée de la Civilisation after it was completed in 1980. Since then, many objects from the Coverdale Collection-previously known as the Canada Steamship Lines Collection-have been on display in various exhibits.

Images of Canada

Hôtel Tadoussac's collection is now a central part of Quebec's national heritage collections. On the other hand, Manoir Richelieu's collection will become an major part of Canada's cultural heritage collections. Since 1968, the hotel, and the collection it houses, has been the property of the Warnock Hersey Company. In 1970, the company offered to sell the collection to the Canadian government for one million dollars. Experts appointed by the State Secretary considered it to be the last existing major private collection in the Canadiana domain (NOTE 10). The collection was purchased for the sum of $875,000 and given over to the care of Public Archives of Canada and of the National Gallery of Canada.

At that time, the federal government had just established a new cultural policy and so, the Coverdale Collection was considered to be an excellent opportunity to offer the general public an exposition of a wide variety of images of Canadian culture and history (NOTE11). In 1970, the Secretary of State decided to put the new acquisition on display at the opening of the new Canadian Cultural Centre in Paris. As for the Public Archives, it is the Canadian government's intention to increase the number of expositions featuring their collections available to the general public, in order to comply with new governmental policy of "promoting and sharing cultural resources." As early as 1973, an exhibition with a hundred pieces of the Coverdale Collection was put on display; the exposition was shown in eight Canadian cities and in three American cities.

It was once again the nationalist current sweeping the country, motivated by the fear of seeing pieces of cultural heritage leave the country, that played a major role in the government's decision to purchase the Manoir Richileu Collection, particularly since the Warnock Hersey Company had considered auctioning the collection if the Canadian government refused to purchase it. Most experts had believed that most of the buyers would have been Americans. As for the Quebec government, despite the interest it had shown a few years back for this part of the collection, it didn't seem to have been included among potential buyers at the time.

From Private Collection to Collective Heritage

The transfer of the Coverdale Collection from private hands to public domain at the very beginning of the 1970s was largely the result of thirty years having it on display to the general public, for this had made it possible for the collection to be widely known. Since William H. Coverdale's passing in 1949, the future of his rich and varied collection had been uncertain. Repeated fears of seeing the collection being disassembled and sold to different collectors or to Ontarian or American museums ended up pushing various levels of government to act. The acquisition of the collection at two levels of national government ensures the preservation of artefacts now considered as part of Canada and Quebec's collective heritage. Such official acquisitions demonstrate the importance the Coverdale Collection holds for many whether at a national or provincial level. From that moment on the Collection became point of reference further development of all other heritage collections regionally and nationally. To sum it up, William H.Coverdale's legacy has become a part of the collective cultural heritage of Quebec and Canada.

Nathalie Hamel, Ph. D.

Ethnologist, heritage and museology consultant

NOTES

Note 1: Marine Museum of the Great Lakes at Kingston (MMGLK), Canada Steamship Lines (CSL) Collection, 1993.2.186, Canada Steamship Lines, The Normandy of the New World, 1934, p. 23; Collard, Passage to the Sea; France Gagnon-Pratte, Le Manoir Richelieu, Quebec, Continuité Editions, 2000.

Note 2: René Brimo, L'Évolution du Goût aux États-Unis d'après les Collections, Paris, J. Fortune, 1938, p.77-78; Bruno Pons, Grands décors français, 1650-1800: reconstitués en Angleterre, aux États-Unis, en Amérique du Sud et en France, Dijon, Faton, 1995, p. 96-107.

Note 3: "[It is ...] not only for the pleasure and edification of people of our own time, but for those who, in generations to come, will inherit a deep reverence for the rich and colourful story of the Dominion of Canada." Bibliothèque et Archives Nationales du Québec, Centre d'Archives de Québec (BAnQ-Q), Fonds Ministère des Affaires culturelles (MAC), E6, 1980-00-025/6, Percy F. Godenrath, Catalogue of the W.H. Coverdale Historical Collection of Canadiana and of North American Indians at The Manoir Richelieu Murray BayP.Q., Canada Steamship Lines, Montreal (multiple editions: 1930, 1932, 1935, 1939).

Note 4: For additional examples, see : Commission des Monuments Historiques de la Province de Québec, Deuxième Rapport de la Commission des Monuments Historiques de la Province de Québec, 1923-1925, [Quebec], Commission des Monuments Historiques de la province de Québec, 1925, p. XVII.

Note 5: Anonymous, Canada Steamship Lines, Collection de l'Hôtel Tadoussac, 1968, 4 p.

Note 6: Léon Bernard, "La Collection Tadoussac au Musée du Québec", Perspectives Dimanche-Matin, October 26th1968, p. 4.

Note 7: Lucia Ferretti, "La Révolution Tranquille", L'Action nationale, LXXXIX, 10, December 1999.

Note 8: Giuseppe Turi, "Les Problèmes Culturels du Québec", Montreal, La Presse, 1974, p. 31.

Note 9: In fact, after 40 years of acquisitions, in 1964, the Musée du Québec owned 2,315 paintings and drawings, 821 sculptures, 1,813 pieces of decorative art, 331 artisan works and 21 images. Jean Hamelin and Cyril Simard, Le Musée du Québec: Histoire d'une Institution Nationale, Quebec, Le Musée, 1991, p. 31.

Note 10: Similar comments were made during the acquisition of the Peter Winkworth Collection by the National Archives of Canada.

Note 11 : André Fortier and D. Paul Schafer, Historique des Politiques Fédérales dans le Domaine des Arts au Canada (1944-1988), Ottawa, Conférence Canadienne des Arts/Ministère des Communications, 1989; D. Paul Schafer, Aspects de la Politique Culturelle Canadienne, [Paris], Unesco, 1977, 97 p.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Collard, Edgar Andrew. Passage to the Sea: The Story of Canada Steamship Lines, Toronto, Doubleday Canada, 1991.

Cooke, W. Martha E. Collection d'oeuvres canadiennes de W.H. Coverdale : peintures, aquarelles et dessins : collection du Manoir Richelieu, [Ottawa], Archives publiques Canada, 1984, 299 p.

Godenrath, Percy F. Catalogue of the W.H. Coverdale Historical Collection of Canadiana and of North American Indians at The Manoir Richelieu Murray Bay P.Q., Canada Steamship Lines, Montréal (plusieurs éditions : 1930, 1932, 1935, 1939).

Hamel, Nathalie. « La construction d'un patrimoine national : biographie culturelle de la collection Coverdale », thèse de doctorat, Québec, Université Laval, 2005, 396 p.

Hamel, Nathalie. « Un musée amérindien à Tadoussac : le projet de William H. Coverdale », Ethnologies, vol. 24, no 2, 2002, p. 79-105.

Hamel, Nathalie. « Controverses autour d'un objet : Les boiseries de la maison Estèbe à Québec », dans Martin Drouin (dir.), Patrimoine et patrimonialisation du Québec et d'ailleurs, Québec, Éditions Multi Mondes, 2006 (coll. « Collection Cahiers de l'Institut du patrimoine de l'UQAM » ; 2), p. 155-172.

Tremblay, François, et Musée régional Laure Conan (1979), William Hugh Coverdale, collectionneur: chronologie de Pointe-au-Pic (Manoir Richelieu) et de Tadoussac (Hôtel), La Malbaie, Musée régional Laure Conan, 63 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Castor d'Amérique, 18

Castor d'Amérique, 18

44 -

Cerf de Virginie, 184

Cerf de Virginie, 184

8 -

Hôtel Tadoussac à Tad

Hôtel Tadoussac à Tad

oussac -

L'Ange-Gardien et, su

L'Ange-Gardien et, su

r l'autre rive ...

-

Le cap Diamant à Québ

Le cap Diamant à Québ

ec, Bas-Canada ... -

Le Cône de glace de l

a chute Montmor... -

Le Cône de glace de l

a chute Montmor... -

Le Fort Chambly. extr

ait de l'ovrage...

-

Le salon Murray, Mano

Le salon Murray, Mano

ir Richelieu (L... -

Le transport de la gl

ace -

Manoir Richelieu à Mu

Manoir Richelieu à Mu

rray Bay (La Ma... -

-

Montréal vue du mont

Royal -

Mort du général Wolfe

Mort du général Wolfe

-

Newfoundland, Nova Sc

otia and New Br... -

Patinage sur le fleuv

Patinage sur le fleuv

e Saint-Laurent...

-

Philippe-Joseph Auber

t de Gaspé; ext... -

Portage d'un canot, v

Portage d'un canot, v

ers 1860 -

Portrait du cardinal

Portrait du cardinal

Richelieu, Mano... -

Québec en vue contreb

as de l'église ...

-

Salon principal du Ma

Salon principal du Ma

noir Richelieu ... -

Suite du cours du fle

uve Saint-Laure... -

Vestibule principal d

Vestibule principal d

u Manoir Richel... -

Vue de Montréal vers

le nord-ouest

Documents PDF

-

Article du Toronto World concernant William H. Coverdale (lundi 14 février 1918)

Article du Toronto World concernant William H. Coverdale (lundi 14 février 1918)

-

Article de Nathalie Hamel consacré à la collection Coverdale

Article de Nathalie Hamel consacré à la collection Coverdale

![Le Vieux Québec [Old Quebec] Exhibition, 1942. © BAnQ](http://www.ameriquefrancaise.org/media/thumbs/787/290x0-Le_Vieux_Quebec_1942.jpg)