The Montreal Olympic Stadium Complex

par Bassil, Soraya and Dion, Amélie

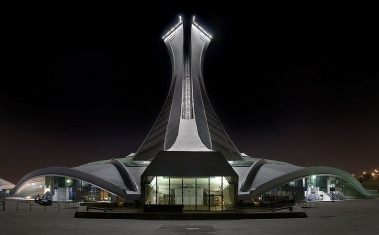

Unique in all of North America, the bold architectural style of the Montreal Olympic Stadium makes the building’s architecture one of the emblems of the City of Montreal. Designed by the French architect Roger Taillibert, in order to host the 1976 Summer Olympic Games, today the building has not only become a part of the architectural heritage of metropolitan Montreal, but also of the Province of Quebec and of Canada. Even though the general populace has a special affection for this piece of organic and sculptural architecture—which testifies to the international significance of an event that marked the rising of modernism in the Province of Quebec—many facets of the story how it was built and its short, but varied history remain unknown.

Article disponible en français : Stade olympique de Montréal et installations connexes

The Olympic Stadium, a Jewel of Modern Architecture

As an architectural project, the Olympic Stadium has been subject to some of the most intense media coverage in the Province of Quebec’s recent history. For quite some time, its public image was tarnished by the various difficulties encountered as it was being built; the considerable time it took to complete; as well as the substantial over-budget spending that the project incurred. Nevertheless, the media hype, the complex’s distinctive shape and it’s unique position in the eastern end of the metropolis all contributed to making the site an essential feature of the Montreal landscape. The Olympic Stadium can be seen from about anywhere in the city and is often used as a visual landmark, even by pilots flying over Montreal. This predominant piece of Montreal’s urban heritage stands out like no other building in the area.

The Olympic Complex sits on a site located in the east end of the city on a 60-hectare [148.3-acre] lot parallel to rue Sherbrooke. It is closely linked to Parc Maisonneuve and the Botanical Garden, which are located just across the major urban thoroughfare. Built to host the 1976 Olympic Games, the Olympic Stadium stands out against the city’s skyline, due to its 175-metre [574.1-foot] leaning tower (hereafter referred to as the “mast” (NOTE 1)). Interestingly, it is the mast that makes the complex one of the world’s most substantial examples of Oblique Function in architecture (NOTE 2). The structure is also the sixth highest building in Montreal. The first 92 metres [302 feet] of the mast are of concrete, whereas the upper section (completed in 1986) is of prefabricated steel caisson construction manufactured by Marine Industries, in Rimouski, Quebec (NOTE 3).

In spite of the high building cost of the Olympic Complex—a fact that many Quebecois haven’t yet forgotten (to the tune of 1.2 billion Canadian dollars) (NOTE 4)—the stadium and the surrounding facilities are undeniably among the most important heritage assets of not only the City of Montreal, but of the Province of Quebec as well (much like so many other national monuments around the world, such as Paris’ Eiffel Tower, which were at first met with public disapproval and incomprehension before becoming one of France’s national emblems).

The international recognition that the Stadium has received, as well as its striking and enduring presence in the city has gone a long way to raising an awareness of the exceptional value of the site among the people of Quebec. The Stadium was designed as a signature piece of unique visual artwork, all the while remaining remarkably functional. Its elegance and impressive scale make it one of the Province of Quebec’s foremost examples of modern architecture.

A Grandiose Project

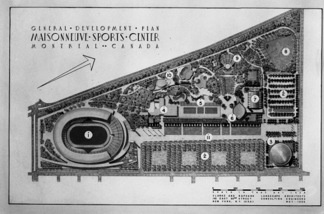

In 1976, Montreal was asked to host the 21st edition of the Summer Olympic Games. Following the example of Munich’s 1972 edition of the Games, Montreal Mayor Jean Drapeau and his cabinet decided to assemble multiple athletic disciplines on one single site, thereby creating a cohesive architectural complex and reducing the necessity of having to move the participants from event to event.

On the site that was chosen, there was already the Centre Pierre-Charbonneau and the Maurice-Richard Arena. Both of are evidence of the city administration’s previous efforts to renew this particular area of town by installing athletic facilities. The modern architecture of the two buildings designed and built during the 1950s would make it possible to integrate them harmoniously into the new organic-style master plan devised by the City of Montreal’s Public Works Department (which were to be reviewed and revised by the architect Taillibert) (NOTE 5).

A research delegation, lead by Charles A. Boileau, then director of the City of Montreal’s Department of Public Works, had a look at several existing sports facilities, both in the United States and in Europe. It was the Parc des Princes de Paris, a stadium constructed using pre-stressed concrete designed by the French architect Roger Taillibert, that particularly impressed the committee. The City of Montreal’s executive committee was sufficiently impressed by Taillibert’s expertise in constructing athletic facilities, building with pre-stressed concrete and designing movable fabric structure systems that it decided to confer the French architect with the project of designing the Olympic Complex. Strongly backed by Mayor Jean Drapeau, who was not only an avid Francophile, but who had also already called on the expertise of French architects for the building of the Montreal Subway, the resolution was passed on April 24, 1973.

The decision resulted in arousing the ire of not only many architects and engineers in the Province of Quebec (who felt that they had been refused the opportunity of designing the grand-scale project), but also many contractors and labourers who would have to learn to work with pre-stressed concrete, a recently developed building method which was largely unfamiliar to them (NOTE 6).

Moreover, the schematic design adopted by Taillibert had to meet several requirements of the constructive program. First of all, the program required that the complex include a multi-purpose stadium in which events for several athletic disciplines could be held. Of necessity it would also include regulation Olympic pools for aquatic sports, as well as a vélodrome [indoor bicycle racing track]. Particular attention was given to the safety of the site; for it was important to ensure that crowds could move freely through the site and, if necessary, be evacuated rapidly. In addition to these requirements, the International Olympic Committee’s regulations stipulated that the competitive events had to take place in an open-air environment or, in other words, an open-air stadium. Furthermore, in the initial plans established by the City of Montreal (who was then overseeing the construction as project owner (NOTE 7)), stipulated that the athletic facilities built for this prestigious although ephemeral event had to later be able to be used throughout the year for baseball (the stadium in particular (NOTE 8)), as well as for other athletic and cultural events. At this point, Montreal’s climate had to be taken into consideration, and thus, the necessity of a roof over the Stadium—as long as it was movable.

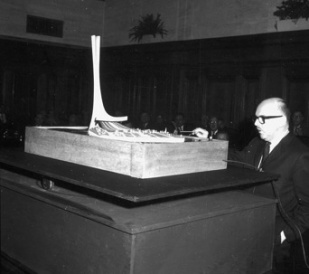

Ever interested in keeping the facilities in close proximity to each other, Taillibert’s plans proposed three main components that would house most of the competitions. While both distinct and integrated as architectural components, these three parts of Tailibert’s design included the Stadium, the Swim Centre and the Velodrome. At the unveiling of the architectural model in 1972, it was already evident that Tailibert proposed building structures that involved exceptionally visually poetic and organic architectural shapes that would be constructed using unconventional building methods. The elliptical shaped stadium was 490 metres [1607.6 feet] long by 180 metres [590.6 feet] wide. Mayor Drapeau affirmed that these dimensions, in such a configuration, would afford all spectators optimal visibility in a sports facility intended to house a variety of athletic events. For this reason, the structure includes a multi-level ring of stands with a seating capacity of 56,000, not including the some 20,000 overflow seats added temporarily to accommodate the Olympic Games. These stands are set on 34 self-stabilising cantilever consoles, which support the technical ring, as well as 20% of the total weight of the movable roof—the remaining 80% being supported by the mast (the tower).

In addition to the main structure of 34 overhanging cantilevered consoles, there was also the mast with its triangular base, whose vaulted interior areas housed the Swim Centre with its regulation Olympic pools built for aquatic competitions. During the Olympic Games, the mast was also supposed to house the palestra and hold up the movable roof, but due to a lack of time, it was decided that this part of the plan would not be completed before the opening of the Games. Designed rise to a height of 175 metres [574.2 feet] and to lean at and angle of 45 degrees, it would become the highest freestanding leaning structure in the world (NOTE9).

The Velodrome is of one of the most single innovative architectural structures built at the time. The vaulted shell of its self-supporting roof flares out from a single bearing point, dividing into three lobes that rest on three additional bearing points. The three lobes of the roof are joined together by two triangular-shaped sections. The roof has a maximum horizontal dimension of 172 metres [564.3 feet] and reaches a maximum height of 32 metres [105 feet]. Structurally, it consists of hundreds of prefabricated voussoirs (wedge-shaped arched panels) (NOTE 10). The building was intended to have a seating capacity of anywhere between 7,000 and 12,000. Later, in 1978, the feat of architectural and technical engineering involved in building the Velodrome would be officially recognised in London by a plebiscite vote of engineers in attendance at the International Congress of Precast Concrete Industry, such was their admiration for the accomplishment.

Chartering a Course through Troubled Waters; the Building of an Athletic Centre

The construction of the Olympic facilities, which began on April 28, 1973, would come to have a negative impact on the entire project. The building project would take place at time when all the major building sites in the Province of Quebec were undergoing politization. This political context would be joined by escalating syndicate rivalry between the two main labour unions, the Fédération des Travailleurs du Québec (FTQ) [Quebec Federation of Labour] and the Conférération des Syndicats Nationaux (CSN) [Confederation of National Trade Unions], which would then lead to two consecutive strikes that would last from November of 1974 into January of 1975, and then again later from May of 1975 to October of 1975. These strikes would result in numerous project setbacks and delays, to the point that, by the end of 1975, it became difficult to determine whether the site would be ready in time for the Games. These setbacks brought about by clashes in labour relations were joined by yet another factor: the rising inflation of the 1970s that increased the cost of certain building materials, such as the steel used to reinforce the various concrete structures of the project. The construction schedule was already tight, to the point of undermining the viability of Montreal’s candidacy as an Olympic city (NOTE 11), but these final developments made the prospect of hosting the Games almost unfeasible. Faced with this turn of events, the International Olympic Committee even began to plan on moving the Games to Mexico.

However, thankfully the Régie des Installations Olympiques (RIO) [Olympic Installations Board, founded on November 20, 1975] intervened, reorganising the building project, thereby stabilising the volatile working climate that prevailed on the construction site, as well as increasing productivity rates for the pre-cast concrete sections at the Shockbeton manufacturing plant (NOTE 12). And so, in the end, the facilities were adequately ready to host the Olympic Games, although the site was not entirely completed at that time. The mast only rose to 59 metres [194 feet] of it its planned total of 175 [574.2], the stands were temporary and the landscaping was only partially completed.

And so, in spite of all the preceding obstacles, the opening ceremony of the 21st modern Olympic Games took place as planned on July 15, 1976, with a procession of athletes from the various delegations representing 94 countries in attendance, as they filed before a crowd of 76,433 spectators. Two weeks of competitions followed, marked by the exploits of the young Romanian gymnast, Nadia Comaneci and the noticeable absence of any African presence in the Games—both remarkable moments in the history of the Montreal Olympic facilities. In spite of all the sceptics, the general populace is impressed by the expressive eloquence of the Stadium complex’s architecture.

This memorable event (in which Canada won 5 silver, 6 bronze, but no gold medals—a first for a hosting country) has left noticeable marks on the site as well as on the collective memory of the community. In fact the event was so memorable for Quebecois, that in 1986, Montreal celebrated the 10th anniversary of the 1976 Games in pomp and ceremony. For the occasion, a plaque commemorating the medallists’ athletic performances was set up in a place of honour. Although the prestige, honours and excellence of the Games went a long way to restore public opinion of the Olympic facilities, the saga of the Montreal Stadium was far from over.

International Acclaim

In spite of the financial and political unpleasantness on the construction site and the debt amassed while constructing of the main components of the Olympic facilities (the Stadium, Velodrome, Swim Centre and the Olympic Village)—a debt whose reimbursement would be drawn out over three decades (NOTE 13)—positive effects from hosting the 1976 Olympic Games would nevertheless be immediately felt in several sectors. A few examples of such effects would include, among others, the athletic facilities housed in the Olympic Stadium Complex that were made available to the general population of the City of Montreal after the Games, the increased touristic affluence generated by Montreal’s newly acquired status as an international city, as well as the founding of a large number of athletic associations. Interestingly it is not only these associations that can trace their historic origins back to the 1976 Games, but also the practice of organised amateur sports in the Province of Quebec.

It wasn’t until 1984 (NOTE 14) that the project to finish building the mast began, thereby making it possible to finally complete the Stadium in accordance with Taillibert’s original plans (NOTE 15). Regardless, the Olympic facilities were not any less functional in 1976, for all the events held there were very popular (NOTE 16). The facilities hosted a variety of events that were widely appreciated by the general public. Probably the most notable such event was when Montreal’s professional baseball team, the Expos, took up residence in the Olypmic Stadium on April 15, 1977. For many years, the Expos would stir the fans’ fervour and rock the crowds, until a series of disappointing performances combined with serious financial problems would gradually cause a decline in public interest for its “very own” baseball team. This continued for some years, until it became necessary to sell out and move the team to Washington in 2004.

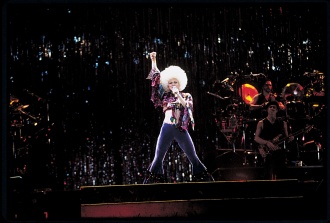

Over the years, many major athletic as well as cultural events contributed to the widespread fame of the Montreal Olympic facilities. The Stadium was often the venue of choice for holding large-scale public demonstrations, particularly because it was easily accessible and made it possible to safely host vast crowds (NOTE 17). Among the many memorable events is Pope Jean-Paul II’s visit on September 11, 1984. On that occasion, his holiness addressed crowds of more than 60,000 youth aging anywhere from 16 to 25 years old and Céline Dion sang Une Colombe, a performance that went down in history as a remarkable moment in her singing career. The same year, Diane Dufresne’s show Magie Rose [Pink Magic] was met with resounding success. Dufresne is the only artist from the Province of Quebec to ever have presented their solo show in the Olympic Stadium. Many international pop stars have also walked the stage of the Olympic Stadium, including AC/DC, Genesis, Metallica, Guns N’Roses, Pink Floyd, Madonna, Michael Jackson and many others. The Stadium was even the venue for Puccini’s opera Turandot, as well as for the shooting of several scenes for various films. Other major athletic events have been held there, such as the 1977, 1979, 1981, 1985, 2001 and 2008 editions of the Canadian football Grey Cup, as well as various runaway soccer match and a world first, the 2006 Outgames. The Stadium has also hosted many major trade-shows and exhibitions (NOTE 18).

A Piece of Quebec Heritage Still under Construction

The Olympic Complex requires constant maintenance, but some of the facilities added on over the years have improved the site. And so, a glassed-in cable car on the outer surface of the tower, which whisks visitors to the upper levels of the mast, was inaugurated on November 22, 1987. Its unrivalled height and unobstructed view of Montreal make the Observatory a major tourist destination. The excellent panoramic view of the city from the tower observatory was awarded a 3-star rating from the Michelin Green Guide in 1992 and the buildings of the Olympic Complex are listed as architectural points of interest. In 1987, a further even more significant improvement to the complex was finally completed: the stadium roof. Just as planned in the original blueprints, the roof was a movable Kevlar membrane covering a heretofore-unsurpassed surface area of 23,270 square metres.

This solution for covering the Stadium roof proved however to be only temporary, for the premature wear on the roof membrane caused it to tear several times during the 1990s. And so the RIO was called upon to have a new roof designed and installed, which this time was permanent (unmovable). Thus, in 1998, the Stadium was capped with a flexible, but fixed membrane consisting of a mesh of cables covered with 63 fibreglass panels coated with Teflon. Several months later, due to one of the panels collapsing under the weight of the accumulated winter snow the Montreal International Auto Show was cancelled, even though show set-up was already underway. This resulted in restricting access to the central floor area of the Stadium for the winter, limited access being only available upon the fire department’s approval. In 2004, the RIO announced its intentions to install a new fixed roof, in order to make the vast central area of the stadium accessible all year long with no restrictions. In the end, Taillibert’s original objective of fabricating the world’s very first movable textile membrane roof turned out to be impossible to attain. As for the numerous alternative proposals submitted by the engineers, they demonstrated just how challenging it could be to find a solution for replacing an architectural component that is in keeping with the original style.

As for the Velodrome, due to the facility’s usership and profitability it became necessary to change its function. Once the Olympic cycle teams had left, the building was determined to be underused, and so it was transformed into a science museum whose interpretative focus largely dealt with ecosystem diversity. Christened the Biodome, the museum opened in 1992. It was ceded to the City of Montreal the same year on the occasion of the city’s 350th anniversary. Even though the Biodome became an educational centre and tourist mecca whose interpretative services complemented Montreal’s other nature museums in perfect harmony (e.g. the Botanical Garden and the Montreal Insectarium, both located nearby), as well as contributing remarkably by promoting and increasing visitor traffic using the Olympic site, one must not forget to mention the major transformation that the interior of the Velodrome underwent. Although these changes were necessary, they would thereafter make it impossible for visitors to appreciate or even imagine how the structure once looked and how the architect Taillibert originally intended that it be used. Such was the consequence of meeting the considerable challenge that the RIO had to deal with in order to increase the profitability of a large building that was very costly to maintain. Sadly, it had to be done at the expense of some of its fundamental architectural characteristics.

Promoting the Olympic Stadium and its Heritage

Over the years, the Olympic facilities have stirred up the bitter criticism of some of the most critical journalists and caricaturists. Nevertheless, 80% of all Quebecois are said to have a positive opinion of the Complex (NOTE 19). In spite of its lively controversial history, the Stadium remains a remarkable accomplishment that will eventually find its rightful place as a part of the Province of Quebec’s architectural heritage for many generations to come. For no other building, neither in the province nor elsewhere in Canada can even begin to compare with the singular uniqueness of the Montreal Olympic Stadium—and it seems that it is here to stay and it will be around for a long while yet.

Not only did Taillibert succeed in innovating techniques while building the Montreal Olympic Park (the Stadium was the first time an integrated approach for pre-stressing and post-tensioning concrete, as well as for using structural textiles that had ever been used (NOTE 20)), but the architect also was successful in meeting his objective of successfully designing, creating and completing a sports complex that could truly be described as a “master work of art.”

The artistic qualities of the complex are self-evident, as much in the thin self supporting web-like structure making up the roof of the Velodrome and the Swim Centre, as in the elegant load-bearing framework of the Stadium—which was not only the result of assembling prefabricated units of different sizes, but also the architecture of the textile roof structure that was designed to remain suspended between a vertical load bearing architectural component (the mast) and a tensioned, movable hanging component (the Kevlar roof membrane). In a way, the whole was a successful first, even though this particular roof design didn’t benefit from a thorough understanding of the extreme winter temperatures so prevalent in the Province of Quebec.

Since that time, various architects and architecture historians, such as Luc Noppen and Jean-Claude Marsan, have spoken out in favour of the site, thereby redeeming some of its excellent qualities. They emphasise that the Olympic Complex testifies to the recent evolution of Quebec society and is an eloquent example of visually poetic architecture whose aesthetic value should be appreciated and preserved. Yesterday’s grievances have already begun to fade away, for the population has once again begun to take ownership of this very unique piece of urban heritage; the controversial complex has become widely acceptable symbol of Quebec and its society (NOTE 21).

Much like the example of the “Bird’s Nest” Stadium built for the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, the Montreal Stadium has become deeply rooted in the history of the Modern Games. The grand ideals behind the event inspire architects to seek to surpass each other, ever creating fresh new architectural concepts that never cease to capture the imagination of the public. Roger Taillibert also sought to do so, and so he endeavoured to design and create a feat of architecture that demonstrated an extraordinary level of mastery of his art. In so doing, he succeeded in surpassing, in transcending the traditional boundaries of what at the time was considered to be the highest standards for athletic stadiums, in order to create his very own exclusive signature brand of visual artwork in architecture. It is this very quality that still emanates from this monument to modernism.

It is only once the Games are over that the works of architecture that they inspired begin to find their actual purpose and meaning. It is then that they begin to acquire their true heritage value, whether great or small, as the public begins to find a use for them—and in so doing, they appropriate them. Today the Olympic Stadium is a fixture in the lives of all Montrealers and has found a place in the hearts of Quebecois across the province. It is certainly one the building that represents contemporary Montreal, just as Jean Drapeau had planned when he had it built. In order to preserve the site in all its integrity, as well as to increase its heritage value, a plan should be set in place for officially recognising the heritage significance of the Olympic Stadium by classing it as a historic monument under Quebec’s Cultural Property Act.

Soraya Bassil

Museologist, modern heritage conservation specialist, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

Amélie Dion

Art Historian, modern heritage conservation specialist, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM)

NOTES

1. The term “mast” was used by the architect Taillibert as an analogical reference to the mast of a sailing ship, which held up the sails. In the context of the Stadium, the “mast” held up the weight of the movable textile membrane of the roof, which Taillibert called the “Umbrella of the Stadium.” Taken in this sense, the mast and the roof as an ensemble could be said to have an architectural synergy that defined the very material and conceptual coherence of their relationship. “Montreal Tower” is however the term most often used by the Régie des Installations Olympiques (RIO) [Olympic Installations Board].

2. This is the term used by Marc Emery in his writings on Taillibert.

3. The original plans drawn up by the architect Roger Taillibert called for a mast made entirely of concrete. However, following an analysis carried out by the Quebec engineering firm SNC Lavallin it was suggested that the colossal weight of such an entirely concrete structure had inherent risks (it was too heavy to be structurally sound). That is why the upper section was built using steel.

4. According to the figures taken from “Finances – Parc Olympique, Minstère des Finances – Gouvernement du Québec,” Rapport final du COJO, it costed exactly $1,286,069,000. This didn’t include the cost of building the Olympic Village, as well as that of converting the Velodrome into the Biodome.

5. Here one notices that the Olympic complex infrastructures were aid out in alignment with rue Sherbrooke instead of with rue Camillie-Houde, as originally proposed in 1956 by architects Clarke and Rapuano. This arrangement allowed for greater synergy between the already existing infrastructures and those that were to be constructed, thereby establishing a meaningful connection between the “inorganic” concrete structures of the Olympic complex and the “organic” vegetation of Parc Maisonneuve.

6. One must mention that other renowned foreign architects had already left their mark on the Montreal landscape in the 1960s, without raising such a commotion. Furthermore, at the time, other renowned architects were already using pre-stressed concrete building methods in the United States and Canada (e.g. the Louis Kahn & August Kommendant duo while building the Jonas Salk Institute for Biological Studies, La Jolla, California (1959-65), as well as the Moshie Safdie & August Kommendant duo for the construction of Habitat 67, Montreal, Quebec (1967). Nevertheless, pre-stressed concrete building methods are little used and hardly developed, compared with methods for pouring concrete on site, which also can be used to build very bold, innovative structures, such as those of Eero Saarinen, whose architectural style consists of seemingly malleable shapes and qualities that can be compared to those visible in some of Taillibert’s projects (see Trans World Flight Center at New York’s John F. Kennedy International Airport (1956-1962)).

7. At the beginning of the 1970s, the City of Montreal was the project owner of the Olympic Complex. It wasn’t until Law 81 for the incorporation of the Régie des Installations Olympiques (RIO) [Olympic Installations Board] was passed on the 20th of November of 1975 that the Quebec Provincial Government became the project owner. With the exception of the Biodome, which was given to the City of Montreal on the occasion of its 350th anniversary, the remaining facilities of the Olympic Complex have not to this very day been retroceded to the City of Montreal.

8. Taillibert’s basic design is that of a baseball stadium, exactly as he states in his book Construire l'avenir [Building the Future](1977), p. 50: “I was given the objective of building a stadium suitable for playing baseball (an already popular sport which would make the facilities profitable on a long term basis) that would only host the Olympic competitions for a short 15 days, but would later need to become a useful asset to the Montreal community.” On page 60 he adds: “The playing field or arena for a particular sport (whether baseball, American football, soccer or boxing) predetermines the spectator’s viewing needs, which is the main reason why such large scale structures need to be built.”

9. Taillibert and Emery write that in the plans, the vaulted interior of the mast would house several open plan areas that could be developed for specific uses: “At the top there will be a restaurant with a panoramic view that can be accessed using an observation elevator also with a panoramic view (Taillibert, 1977: p. 62).” Emery states: “The mast is a bold and original example of the Oblique Function in architecture; the top part, at 168 metres [551.2 feet] tall overhangs the base by 65 metres [213.2 feet]. There are 18 floors in the mast which are divided up into various athletic equipment rooms and training halls. They can be accessed using the glassed-in cable car, as well as two elevators. At the base of the mast, spreading from one end to the other, is the 10,000 square-foot Swim Centre (1976: p.43-44).”

10.A voussoir or quoin is a traditional architectural component cut out of stone to be used to build a vault or arch

11. A project of such magnitude usually required 5 years to build, but the building schedule only allowed for three years to build the Olympic facilities.

12. This company was the only one to submit a proposal for the pre-cast concrete. In fact its Shockbeton plant was constructed in order to manufacture the pre-cast concrete sections need for the Olympic site.

13. The arrangements made for the financing of the Olympic Complex are unique, for the Stadium and the surrounding athletic facilities are the only public buildings to have granted a mortgage in their own right, this arrangement made it possible to pay the entire debt off. This is however not the case of other public buildings whose construction costs are allocated to expenses consolidated at the various levels of federal, provincial and municipal government. In so doing, these expenses still are incorporated into Quebecois’ total public debt.

14. Even though the first attempts to finish the mast date from June of 1979.

15. The exterior of the Stadium has been completed in accordance with the building plans, but those for the interior have not been followed to the letter; not even the mast, which is partially constructed of steel instead of concrete as planned.

16. Since 1977, “the central area of [of the Stadium], which includes the stands” is in use on an average of 193 days a year. This enables the RIO to generate a significant revenue of more than 20 million dollars each year. The Stadium alson creates major spin-off generated by the various events that take place onsite, as well as from local, national and international tourism.

17. The main area can hold more than 60,000 people.

18. Shows and events such as the Montreal International Auto Show, Montreal Motorcycle Show, Salon international de la Jeunesse [Youth Show], the RV Show and the Cottage & Country Homes Show.

19. According to the Sondage Léger Marketing survey carried out in March of 2009 (1500 participants in the Province of Quebec).

20. To learn more about the accomplishments of this great architect, see the additional PDF document in the annexes titled “The Orgins and Evolution of Taillibert’s Architectural Style”.

21. Jean Drapeau said it so very eloquently when speaking to a journalist from the La Presse in 1986: “The Stadium will last and become the very proof of the quality of its workmanship.” In 1985, Marcel Léger, then Minister of Tourism spoke already in visionary terms, when he said that the Stadium could very well become an iconic symbol for the City of Montreal, just as the Eiffel Tower is for Paris.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Specialised Reference Materials on the Building of the Complex

Emery, Marc, Roger Taillibert, architecte | RogerTaillibert, Architect, Montréal, Éditions 1976, 1976, 79 p.

Emery, Marc, René Huygue, Œuvres récentes de Roger Taillibert, Paris, Métropolis, 1977, 119 p.

Morin, Guy R., La Cathédrale inachevée, Montréal, XYZ, 1997, 379 p.

Nora, Pierre, Les lieux de mémoire, Paris, Gallimard, 1984, volume 3.

Orlandini, Alain, Roger Taillibert : réalisations, Paris, Somogy - Éditions d'art, 2005, 211 p.

Ragon, Michel, Histoire mondiale de l'architecture et de l'urbanisme modernes, Paris, Casterman, , 1978, volumes 2 et 3.

Taillibert, Roger, Construire l'avenir, Paris, Presses de la Cité, 1977, 215 p.

A Study of the Events Surrounding the Construction of the Stadium

Caza, Daniel, Les Expos : du parc Jarry au Stade olympique. Montréal, Éditions de l'Homme, 1996.

Specialised Articles

---, « Stade du parc des Princes », Architecture d'Aujourd'hui, n° 164, oct-nov. 1972,p. 90-98.

Noppen, Luc « Le Stade olympique », Continuité, n° 53, printemps 1992, p. 31-34.

Parent, Claude,« Interview Taillibert », Architecture française, n° 401, février 1977-I, p. 37-48.

T.A.A.A., « Architecture mobile », Technique et Architecture, n° 304, mai-juin 1975, p. 33-37.

Taillibert, Roger,« Architecture textile », Technique et Architecture, n° 304,mai-juin 1975, p. 32.

Internet Sources

Taillibert, Roger, Agence d'architecture Roger Taillibert, 2006, www.agencetaillibert.com (Site visited on January 15, 2010)

Régie des installations olympiques, « Historique », La Régie des installations olympiques, Gouvernement du Québec, 2004. (Site visited on December 30, 2009)

Ville de Montréal, Jeux de la XXIeolympiade de Montréal 1976, Ville de Montréal (Site visited on December 30, 2009)

A selection of video clips taken from various television shows [in French], Archives de Radio-Canada (Site visited on January 15, 2010)

Archives

Media file/ Dossier de presse taken from the Eureka database: CEDEROM-Sni inc. EUREKA.CC, [online, member access only], www.biblio.eureka.cc/WebPages/Search/Result.aspx (Site consulted in January and February of 2010).

Media file « Stade Olympique », 1971-1990, Archives de la Ville de Montréal.

Fonds E241, Comité organisateur des Jeux olympiques, 1975-2000, Centre d'archives de Montréal |Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Achèvement du mât en

Achèvement du mât en

acier et instal... -

Appropriation par la

Appropriation par la

population mont... -

Caricature : «Comment

Caricature : «Comment

recouvrir le t... -

Caricature du Stade o

Caricature du Stade o

lympique : «Sta...

-

Cérémonie d'ouverture

des Jeux Olymp... -

Chantier des bassins

Chantier des bassins

du Stade olympi... -

Chantier du stade oly

Chantier du stade oly

mpique -

Chantier du vélodrome

Chantier du vélodrome

, juin 1974

-

Coupe Canada 2008 - G

Coupe Canada 2008 - G

rand prix FINA -

Coupe Grey au Stade o

Coupe Grey au Stade o

lympique de Mon... -

Funiculaire du Stade

Funiculaire du Stade

olympique -

Installation de l'ann

Installation de l'ann

eau technique, ...

-

Installation du premi

er segment de l... -

Intérieur du Stade ol

Intérieur du Stade ol

ympique de Mont... -

La maquette des insta

La maquette des insta

llations olympi... -

La maquette des insta

La maquette des insta

llations olympi...

-

Le chantier du Stade,

le 22 octobre ... -

Le maire Jean Drapeau

Le maire Jean Drapeau

présente le pr... -

Le Stade olympique de

Le Stade olympique de

Montréal vu de... -

Le Stade olympique de

Le Stade olympique de

Montréal, 2006...

-

Madonna (tournée Girl

Madonna (tournée Girl

ie Show) sur la... -

Mât du Stade olympiqu

Mât du Stade olympiqu

e de Montréal, ... -

Mise en place de la t

Mise en place de la t

oile de Kevlar,... -

Mise en place des gra

dins du Stade o...

-

Mise en place du plaf

Mise en place du plaf

ond-caisson du ... -

Observatoire logé dan

Observatoire logé dan

s le mât du Sta... -

Plan d’implantation d

Plan d’implantation d

es installation... -

Prestation du groupe

Prestation du groupe

Genesis au Stad...

-

Sandra Henderson et S

téphane Préfont... -

Spectacle «Magie Rose

Spectacle «Magie Rose

» de Diane Dufr... -

Stade et Esplanade es

Stade et Esplanade es

t (en bas à dro... -

Stade olympique: bass

in de compétiti...

-

Visite du pape Jean-P

Visite du pape Jean-P

aul II au Stade... -

Vue aérienne du mât,

en 1976, avant ... -

Vue aérienne du parc

olympique le 15... -

Vue aérienne du Stade

en 1976

-

Vue intérieure du Sta

de olympique en... -

Vue intérieure du Vél

Vue intérieure du Vél

odrome, 1976 -

Vue panoramique du St

Vue panoramique du St

ade olympique d...

Vidéo

Document PDF

Hyperliens

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 18 novembre 1980: « Le toit du stade » (14 min 12 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 26 novembre 1986: « Un Taillibert pour couvrir le stade » (6 min 18 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 30 juin 1985: « Accueil triomphal au Stade olympique » (3 min 22 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 29 septembre 2004: « Dernier match des Expos à Montréal » (6 min 19 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 27 novembre 1977: « La Coupe Grey aux Alouettes » (6 min 23 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 17 septembre 1984: « Michael Jackson et le Victory Tour à Montréal » (2 min 14 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 16 décembre 1989: « Un spectacle pour toute la famille » (5 min 25 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 11 septembre 1984, « Vive le pape! » (7 min 33 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 14 septembre 2000, « Le maire et l'architecte : Taillibert à Drapeau », (22 min 25 s)

- Radio-Canada (télévision), 14 juillet 1996, « Le Stade, cathédrale inachevée », (14 min 04 s)

![Panoramic view looking out over the east of Montreal, taken from Mont Royal. In the foreground the Mont-Royal Plateau. A bit further back, the Olympic Stadium with its 175-metre [574.1-foot] leaning tower. In the background, the Saint Lawrence River. July 2002.](/media/thumbs/4412/660x152-Montreal_panorama_Stade_2.jpg)