Montmorency Park

par Caron, Jean-François

Montmorency Park (le parc Montmorency) is located at the top of the Côte de la Montagne, near the Bishop’s Palace and the Old Post Office. It was designated a national historic site in 1949 to commemorate one of the places where the Assemblée législative of the Canadian province met between 1841 and 1866, an important milestone in the history of democracy in Canada. Other events and buildings have enriched the past of this spot, which has been in turn a sacred place where pioneers of New France were buried, a place of religious and civil power, and a strategic military site. Montmorency Park has been the scene of major historical events.

Article disponible en français : Parc Montmorency

An exceptional heritage value

The site is today one of the few public parks in Old Quebec. It has lawns, mature trees, and a network of paths providing easy access. There are no buildings still standing, but a number of plaques and commemorative monuments have been installed.

This park possesses great heritage value, especially for the important buildings that have stood there one after the other. On the east, at the top of the cliff, it is bounded by a section of the fortification walls of Quebec City, the Assembly Battery, a tenaille, and part of the Grande Batterie. Many archaeological vestiges are also found there, including those of: defence works; the Bishop’s Palace; the successive parliaments of Lower Canada, the province of Canada, and the province of Quebec; several civic buildings; and the first cemetery of New France. Finally, aspects of the terrain and a number of views recall that this place has been an important fortified site.

1616-1792: a site of many functions

The history of the site begins in 1616, when Récollet missionaries cultivated a garden there. In 1618 they traded this plot for one that Louis Hébert owned on the banks of the Saint Charles River. This informal exchange was made official in 1623 when Henry II, duc de Montmorency, viceroy of New France, granted the title to Louis Hébert. It was the first land grant in the Saint Lawrence valley. In 1626 the new viceroy, Henri de Lévis duc de Ventadour, made it a noble fief, the fief of Sault-au-Matelot, the colony’s first seigneury. Over the following decades successive owners added to the list of titles. Prestigious occupants followed one after the other, from the Hébert heirs to François Provost, major of the city and of the château of Quebec, and including Anne Gagnier, whose son-in-law was Denis-Joseph Ruette, sieur d’Auteuil, procureur général of the Sovereign Council and seigneur of the Monceaux arrière-fief (away from the river) of the Sillery seigneury. The intendant Jean Talon also owned it for a time. Finally in 1688 Mgr Jean-Baptiste de La Croix de Saint-Vallier, the second bishop of Quebec and successor to Mgr François de Laval, acquired the land. To it was later added the neighbouring lot occupied by the first cemetery of the city, and other parcels of land were separated from it, so that in 1732 the present-day limits of Montmorency Park were fixed.

In acquiring this land, Mgr de Saint-Vallier also bought the three-story stone building located there. This building served as the first bishop’s palace and as the seat of the Diocese of Quebec. The next year the bishop began construction of a masonry wall around his property. From 1693 to 1695 he had a new palace built of dressed stone. Of his ambitious project, only the southwest wing was built. After his death, only Mgr Pierre-Herman Dosquet and Mgr Jean-Marie Dubreuil de Pontbriand lived in the new palace, from 1729 to 1732 and from 1741 to 1759 respectively.

At the time of the siege and capture of Quebec in 1759, the building was partially destroyed and the vaults were looted. After that time, the chapel was used for services by the Anglicans of the city. It also served for various public meetings. However, it was only in 1766 that Jean-Olivier Briand, the new bishop, had the whole palace restored. In debt as a result of this work, he agreed to rent the building to the government in 1777, and governor Guy Carleton and his legislative councillors met there. This was the beginning of the political use of the site, although the Bishop’s Palace had temporarily housed intendant Michel Bégon and the Sovereign Council when the indendant’s palace burned in 1713.

Political use of the site is confirmed

With the proclamation of the Constitutional Act of 1791, Quebec City became the political capital of Lower Canada, though without a parliamentary building. As the Bishop’s Palace was the most appropriate building, the first session of the Legislative Assembly met there on 17 December 1792. In 1831, after several years of wavering, Mgr Bernard-Claude Panet finally agreed to sell the Bishop’s Palace to the government. It thus became a real “Hôtel du Parlement”. A series of projects to enlarge and restore it began. Once completed, the building was magnificent. But on 1 February 1854, when the work was barely finished, a fire completely destroyed the new parliament (NOTE 1).

In the meantime in 1840, the British Parliament adopted the Act of Union, which created the United Province of Canada. As a result, Quebec City’s title was changed from capital to “Vieille Capitale” (Old Capital), as the Legislative Assembly met in Kingston. However, at the request of the members, the new capital was very soon transferred to Montreal. The Assembly met there from 1844 to 1849, when a mob set fire to the parliament building to protest against the law compensating the inhabitants of Lower Canada who had lost property during the rebellions of 1837-1838. The capital was again forced to move, and the principle of a “perambulating capital” was adopted. The Assembly would meet alternately in Toronto and in Quebec City. Quebec’s first turn came in 1852. The members met there until 1855, then from 1860 to 1865, when Ottawa was finally chosen by Queen Victoria to be the permanent capital. After the 1854 fire, with the Assembly’s return to Quebec planned for 1860, a new building was built in 1859 and 1860. Intended to serve as post office when the capital moved to Ottawa, the new Parliament was generally described as an undistinguished building.

With the coming of Confederation in 1867, Quebec City was chosen as the capital of the new province of Quebec. The old colonial parliament thus became the seat of the new provincial government. However, the building soon proved to be too small to house all the ministries. In 1872 a new post office was built on the other side of the Côte de la Montagne, and in 1876, construction of a new Parliament Building was begun on the site known as Cricket Field, across from the fortifications (NOTE 2). The legislators and civil servants moved in sooner that planned, since on 19 April 1883 the old Parliament Building was once more destroyed by a fire.

Military uses

In addition to its religious and political roles, the site of Montmorency Park also had a military function. Its position overlooking the extensive Quebec harbour offered an unmatched view of the river, the Pointe-Lévis, the Île d’Orléans and Baie de Beauport. In 1711, the military engineer Jean-Maurice-Josué Boisberthelot de Beaucours built the Clergy Battery (Grande Batterie) near the bishop’s palace. After the Battle of the Plains of Abraham on 13 September 1759, the English made quick repairs to the ruins of the palace to house troops. In 1762, James Murray noted the strategic importance of the site and had another battery constructed, just behind the palace. In 1797 the Prescott Gate was built to control access to the upper city by the Côte de la Montagne, then from 1808 a wall was erected between the Clergy Battery and the Prescott Gate. The Assembly Battery and the Prescott Battery were then installed.

A public park

Development of the Montmorency Park that we know today was inspired by the nineteenth-century romantic ideal of urban beautification, along with the project to preserve the fortifications that was proposed by Lord Dufferin, the governor general. In 1883, after the Parliament Building fire and the departure of British troops in 1871, the site of the old bishop’s palace was vacant and scattered with ruins. In June 1893, after a cleaning, the federal government rented the site to Quebec City. It was made into a public garden, the “parc Frontenac”, though the name was not very suitable since the park was near a prestigious new hotel of the same name. For that reason, in 1904 some citizens submitted a petition to the city council to have the name changed to “jardin Montmorency”, which they considered more appropriate. Their proposal was to honour the memory of a viceroy of New France, Henri II, duc de Montmorency, and of Quebec’s first bishop, Mgr de Laval, a member of the prestigious Montmorency family of France. Thus in 1908 Montmorency Park was officially born. The park’s stone wall was at that time bordered by an acacia hedge, and its red sand walks and greenery were shaded by large willows. Near the fortification wall was a pavilion like the ones still found on Dufferin Terrace. By their action, the citizens secured this place of shared memory.

A focal point of history

Since the beginning of the seventeenth century, the site of Montmorency Park has witnessed a series of events that have made it a focal point of the history of Quebec City and of Canada. When the park was inaugurated during the tricentennial celebration of Quebec in 1908, the commemoration of some of these historical events and people began. In that year the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec had a plaque installed to recall the site of the city’s first cemetery. Then the Société historique de Québec erected a cross there. These first commemorations recalled the religious significance that this part of the site had until the beginning of the eighteenth century, when burials no longer took place there. In 1974 Parks Canada replaced the original cross by a replica, and in 1993 the Fédération des familles souches du Québec added a new plaque commemorating the burial of Indians and French pioneers in this place.

Between 1902 and 1924 the Literary and Historical Society of Quebec also placed several plaques recalling Quebec City military events, including one marking the site of the old Prescott Gate in Côte de la Montagne.

Further north, where the old Parliament Buildings stood, memorials take on a political colouring. In September 1920, premier Louis-Alexandre Taschereau inaugurated a monument to Geoge-Étienne Cartier, prime minister of United Canada and one of the Fathers of the Canadian Confederation. A little later, in 1935, the Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada unveiled a plaque recalling the first patent for a Canadian invention, granted by the Lower Canada Parliament in 1824. Political commemorations continued when in 1949 the Board designated Montmorency Park for its national historical importance. In 1964 the local committee for the diamond jubilee celebration placed a copper plaque on a marble block to mark the place where the Quebec Resolutions, which prepared the way for Confederation, had been signed 100 years before at the 1864 Quebec Conference. Finally, in 1986 the federal Board unveiled another plaque recalling the meeting place of the Legislative Assembly of the Canadian province, as well as the 1864 Quebec Conference.

In May 1966 the memorial flame was revived when a contractor reinforcing the park’s retaining wall discovered archaeological remains. For several weeks the ministers concerned, cultural organizations and the public discussed the future of the park. This event finally led to redevelopment of the site in the early 1970s. As a result of this, the Louis Hébert monument was moved from the Place de l’Hôtel de Ville to the north-west end of Montmorency Park. It had originally been unveiled in 1918 by the Quebec City Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste. Thus the pioneer returned to his land in 1977. This monument recalls not only his memory and that of his family, but also that of forty-seven other colonists who were among the first in New France.

Aside from the official memorials, a careful observer can find other indications of the site’s history. For example, on the outside of the Côte de la Montagne retaining wall, five Board of Ordnance boundary stones still mark the limits of the old military property. The presence of steps leading from the Côte de la Montagne sidewalk to the park recalls the main entrance to the three main buildings that stood one after another at this spot. As a sign that the park has not yet revealed all its secrets, a stone engraved with the year 1815 gives no other clue to its meaning. Finally, the cannons, lined up in a northwest row along the ramparts, confirm the strategic importance of this place for decades.

A balance between preservation and accessibility

Over the years, the people of Quebec City have made this site their own. Whenever a popular cultural event takes place in the historic district of the city, Montmorency Park is taken over by participants, in large part because of its geographical position. As guardian of this exceptional site, Parks Canada faces the challenge of ensuring on the one hand the protection and enhancement of this national historic site, and on the other hand, its use by as many people as possible.

Jean-François Caron

Historian

Société historique de Québec

NOTES

NOTE 1: This is the building where the Quebec city council met from 1845 to 1850.

NOTE 2: That is, at the same place as the present Parliament Building.

Bernier, Serge (Dir.), Québec, ville militaire, 1608-2008, Montréal, Les Éditions Art Global, 2008, 354 p.

Blais, Christian (Dir.), Québec, quatre siècles d’une capitale, Québec, Les Publications du Québec. 2008, 692 p.

Parcs Canada, Énoncé d’intégrité commémorative du LHNC du Parc-Montmorency, Québec, 2004, 35 p.

Têtu, Henri, Histoire du palais épiscopal de Québec, Québec, Pruneau et Kirouac, 1896, 304 p.

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Incendie du premier P

Incendie du premier P

arlement en 185... -

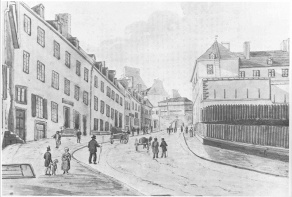

Le Palais épiscopal v

Le Palais épiscopal v

u du haut de la... -

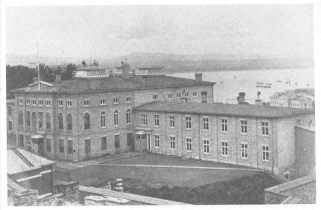

Le second Parlement

Le second Parlement

-

Localisation des plaq

Localisation des plaq

ues et monument...