Migration and the French Language in Nova Scotia: A Recent Portrait

par Fontaine, Louise

Over the course of its history, the population of Nova Scotia has grown increasingly diverse, both from a linguistic and cultural perspective. Without going into the details of this trend, suffice to say that French is a minority language in Nova Scotia today, spoken by only 3 to 5% of the province’s total population. Moreover, the French-speaking population is far from homogenous, since one in four francophones was born outside the province. This linguistic diversity—the result of the comings and goings of people who have settled in this part of Atlantic Canada—represents an unprecedented heritage worth preserving and promoting for future generations.

The Demolinguistic Situation in Nova Scotia: From Yesteryear to Today

Acadians and Francophones in Nova Scotia

Canada has long been a country of immigrants, and was indeed founded on successive waves of immigration that served to meet either the country’s settlement goals or its economic, demographic and humanitarian imperatives. For Nova Scotia, colonization and economic and social development were the driving forces. J. Beck Murray writes: “In 1996 the total population was 899,970, and about 23% of the population were of only British and about 4% of French descent. A further 7% had some British and French. Most of the remainder were of European, Aboriginal and Canadian origins.” (NOTE 1)

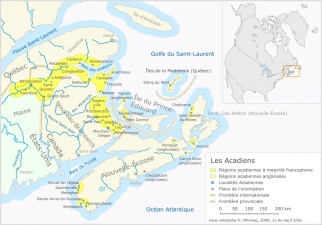

Curiously, this portrait of the population of Nova Scotia drawn from the Canadian Encyclopedia and written by the author of numerous works on the history of Nova Scotia and Atlantic Canada makes no special distinction between Acadians and others “of French descent.” And yet the distinction is important. The word “Acadian” both from a linguistic and ethnological standpoint refers to “a variety of French spoken by Acadians in Canada’s maritime provinces. [...] The Acadia of today is not demarcated by geopolitical boundaries, but rather by cultural and linguistic boundaries. It refers primarily to certain French-speaking regions in the maritime provinces of Canada . . .” (NOTE 2). In this article we will look mainly at the linguistic aspect, touching only briefly on the cultural and historical associations of this polysemous term. It is worth recalling, however, that Nova Scotia’s francophones are mostly, albeit not exclusively, Acadians. Throughout their history they have been a minority, both in terms of their numbers and their access to Nova Scotia’s spheres of influence. However, in Nova Scotia’s recent history, this minority status has been undergoing a transformation. This is one of the points we will examine here.

As Carsten Quell points out (NOTE 3), the term “francophone” can be problematic. In this document we use the Office québécois de la langue française definition of a francophone as someone who routinely uses French in most situations in their daily life (NOTE 4). This definition is not based solely on mother tongue, but rather the language in everyday use.

New Immigrants to Nova Scotia

If we look at the overall international immigration situation in relation to population trends among the established population of the province, the statistics show that in the space of ten years, from 1991 to 2001, a total of 27,051 immigrants settled in Nova Scotia. Of this number only 38% stayed in the province (10,290 people) while 62%, or 16,761, left (NOTE 5).

If we compare population growth rates in Nova Scotia between 1991 and 2001, we see a slowdown, with the rate dropping from 3.30% to 3.03% in 2001 (NOTE 6). This trend can be analyzed using three factors: a) the difference between the number of births and deaths, b) net interprovincial migration and c) net immigration. Low birth rates are creating a negative impact on Nova Scotia’s population growth. The same is true for net interprovincial migration, with a marked exodus of young people, especially those living in rural areas. Lastly, in terms of net immigration trends since 1991, there has been significant variation (NOTE 7). It is worth noting that a total of 2,520 permanent residents were admitted to the province in 2007 (NOTE 8).

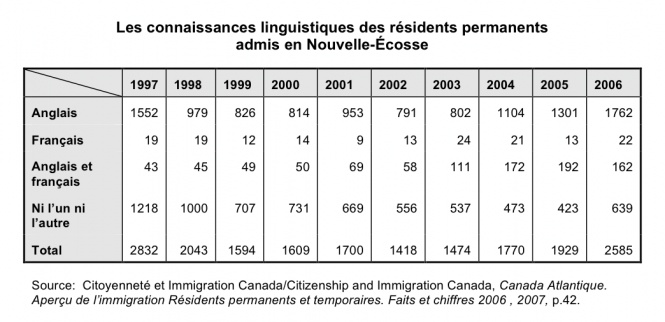

Francophone immigration in Nova Scotia is characterized by relatively significant rates of interprovincial migration. In fact the 2001 census revealed that one in every four francophones was born in another Canadian province. It also appears that francophone immigration in itself is a relatively recent phenomenon, appearing only after 1996. (NOTE 9).

Institutional Structures for the Preservation and Promotion of French in Nova Scotia

For Long-Time Francophone and Acadian Residents of the Province

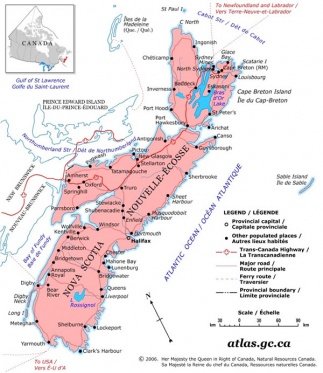

In one of his works, Gratien Allaire presents a series of pertinent historic facts to describe “Nova Scotia Acadians.” He identifies “four zones where Acadians and francophones are concentrated.” The first zone—and the largest in terms of numbers—lies in the southwestern part of the province, between Digby and Pubnico. Second is the geographic zone of Halifax-Dartmouth. The third zone covers parts of Cape Breton Island (Île Madame in the southwest), while the fourth includes the area around Chéticamp (northwest), where Acadians have long been established (NOTE 10).

The author also describes Nova Scotia’s Acadian and francophone associations, pointing to the leadership role played by Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FANE), which was created in 1969, and represents numerous institutional members. Since then a host of organizations have been founded, including Association des juristes d'expression française de la Nouvelle-Écosse (AJEFNE) in 1994, Conseil scolaire provincial acadien (CSAP) (http://csap.ednet.ns.ca) in 1996, Conseil de développement économique de la Nouvelle-Écosse (CDÉNÉ) in 1999, and Fédération Culturelle Acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FéCANE) in 2004. This proliferation of organizations undoubtedly contributed to the passing of the French-language Services Act in December 2004. These examples speak both to the vitality of the French presence in Nova Scotia and the institutional and government recognition of French speakers and Acadians who live in the province and play an increasingly active role in Nova Scotia’s political, economic, cultural and social life.

For Francophones Newly Established in the Province

The French presence in the province manifests itself in a host of ways. At the same time, Nova Scotia is undergoing significant population aging, a trend that led the provincial government to turn to international immigration in the early 2000s to ensure the renewal of its population, including the francophone and Acadian population.

After the federal government passed its Immigration and Refugee Protection Act on June 28, 2002, Nova Scotia’s Ministry of Economic Development signed a federal/provincial agreement with Citizenship and Immigration Canada in August 2002 regarding the creation of the Nova Scotia Nominee Program. Two years later a strategic immigration framework for Nova Scotia was developed. This working document, which led to consultations with various social partners, paved the way for the official adoption of an immigration policy by the Nova Scotia government in January 2005. Since then, the province’s various authorities have dedicated human, financial, material and computer resources to achieving four main objectives: facilitating immigrant reception, attracting immigrants to the province, promoting immigrant integration and retaining immigrants in Nova Scotia (NOTE 11).

Nova Scotia Immigration, a dedicated immigration office, was created in 2005. Since then, community groups and associations have developed projects to attract new French-speaking immigrants to the province and encourage them to stay. Martin Paquet discusses the issue in his article (NOTE 12).

This situation remains paradoxical, however, in that there is a clear trend of migration to other Canadian provinces, both among new immigrants who settle in Halifax and elsewhere in the province (those arrived within approximately 12 months) and individuals (francophones, Acadians, and other residents) who have lived in Nova Scotia for more than a generation.

Globalization and Greater Residential Mobility

In Nova Scotia, as in the other provinces across Canada, there is an ever-growing exodus of young people from rural areas. Many are leaving non-urban areas to study or work in cities like Halifax and Toronto. This geographic mobility has changed considerably since 2000/2001. Individuals and families are leaving parts of rural Nova Scotia to settle in western Canada (mostly in Alberta, but also in British Columbia). Those leaving are of all ages, not just young people in the 18–35 bracket. These migrants are mostly manual labourers who had been relatively sedentary and were long-time residents of the province. The current economic situation in Nova Scotia coupled with the draw of well-paid jobs elsewhere appears to be resulting in greater workforce mobility, as people move to western Canada in hopes of improving their lot in life (NOTE 13). Net migration of Nova Scotia’s French-speaking population went from -265 between 1996 and 2001 to -920 between 2001 and 2006. Net interprovincial migration between July 1, 2005 and June 30, 2006 was -3,930. Across the country, Nova Scotia was second only to Newfoundland and Labrador (NOTE 14). In the wake of the world financial crisis that hit in October 2008, the figures for 2009 show a shift in the trend. For many Nova Scotians, especially francophones and Acadians, Western Canada is no longer the promised land, and Alberta companies have implemented wide-ranging layoffs. The effects of globalization are being felt worldwide.

This recent portrait of Nova Scotia provides food for thought about the movement of populations—notably French-speaking and Acadian populations—who either emigrate to other provinces to live and work there or who arrive from overseas to settle on a relatively temporary basis before leaving for other regions of Canada. This ebb and flow of residents will undoubtedly have an impact on the future of French in the province, as the linguistic and cultural heritage of these individuals—no longer limited to the geographical boundaries of a province or country—becomes increasingly mobile. Nova Scotia’s contemporary demolinguistic situation therefore remains somewhat paradoxical when examined jointly from a migration and French-language perspective.

Louise Fontaine, Ph.D.

Associate Professor, Université Sainte-Anne

NOTES

1. Murray, Beck, J. “Nova Scotia” in The Canadian Encyclopedia, Historica Foundation of Canada, 2008, retrieved 17/07/ 2008 [online], http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com

2. Office québécois de la langue française, Grand Dictionnaire terminologique, 2002, retrieved 26/09/2008 [online], www.granddictionnaire.com

3. Quell, Carsten, Official Languages and Immigration: Obstacles and Opportunities for Immigrants and Communities. Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, Public Works and Government Services Canada, November 2002, p. 5.

4. Office québécois de la langue française, Grand Dictionnaire terminologique, 2003, retrieved 26/09/2008, [online], www.granddictionnaire.com

5. Metropolitan Immigrant Settlement Association, Report on the Nova Scotia Immigration Partnership Conference 2003. Opportunities for Collaboration, July 2003, p.37.

6. Fontaine, Louise, L'immigration francophone en Nouvelle-Écosse. Backgrounder. (In collaboration with Fédération acadienne de la Nouvelle-Écosse (FANE) and Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC), April 2005, p.10, retrieved 16/07/2008 [online], http://fane.networkcentrix.com/media_uploads/pdf/3899.pdf

8. Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Facts and Figures 2007. Immigration Overview: Permanent Residents. Canada – Permanent residents by province or territory and urban area, 1998–2007, modified 11/07/2008, retrieved 22/07/2008 [online] http:/www.cic.gc.ca/francais/ressouces/statistiques/faits2007/02.asp

9. FCFA du Canada [Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne], Profil de la communauté acadienne et francophone de la Nouvelle-Écosse, 2e édition, Ottawa, Ontario, March 2004, p. 4 and p. 8.

10. Allaire, Gratien. “Chapitre II. L'Acadie des Maritimes” in La Francophonie canadienne Portraits. Québec, Sudbury, CIDEF-AFI, Prise de Parole, 2001, p. 64. (Collection Francophonies).

11. Communications Nova Scotia, Nova Scotia Immigration Strategy, January 2005, 35 p. See also Communications Nova Scotia, Strategic Framework for Immigration, working document, August 2004, 54 p.

12. Paquet, Martin, “L'immigration francophone en Nouvelle-Écosse” in Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens. Belkhodja, Chedly (guest editor). Immigration and diversity in minority francophone communities, Spring 2008, p. 99-103.

13. Fontaine, Louise, Migration et mobilité sociale et résidentielle des francophones de la Nouvelle-Écosse. Day of reflection. Immigration and diversity within minority francophone communities. Pre-convention to 11e Congrès national de Métropolis, Frontiers of Canadian Migration/Aux confins de la migration canadienne, La Cité des Rocheuses, Calgary, March 19, 2009 (unpublished text).

14. Statistics Canada. Census 1996, 2001, 2006. Table 8. Net Interprovincial Migration of Francophone Population, Provinces and Territories, 1991 to 1996, 1996 to 200, and 2001 to 2006, modified 12/03/2007, retrieved28/09/2008, [online], http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2006/as-sa/97-555/table/t8-eng.cfm. See also Statistics Canada. Canadian Statistics. Components of Population Growth, by Province and Territory, modified 05/07/2007, retrieved 19/06/2007, [online].

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Atlas de la francophonie. Nouvelle-Écosse. Modification 2005-05-27 [Online]

Fontaine, Louise, « Processus d'établissement, nouvel arrivant et structure d'accueil à Halifax (Nouvelle-Écosse): une exploration de quelques actions concrètes» dansCanadian Ethnic Studies/Études Ethniques au Canada, 2005, vol XXXVII, no. 3, p. 136-149.

Fontaine, Louise, « L'immigration rurale et francophone en Nouvelle-Écosse : quelques pistes de réflexion » dans Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens. Belkhodja, Chedly (directeur invité), Immigration et diversité dans les communautés francophones en situation minoritaire, printemps, 2008, p. 79-82.

Government of Nova Scotia. « La culture acadienne en ligne » dans Tourism, Culture and Heritage, August 13, 2004, Province of Nova Scotia, 2009, page last updated 2009-05-06, site consulté le 6 mai 2009 [Online].

Henripin, Jacques, « Chapitre 12. Les Migrations » dans La métamorphose de la population canadienne, Montréal (Québec), Les Éditions Varia, 2003, p. 209-237. (Collection « Histoire et Société »).

Paratte, Henri-Dominique, Acadians. Nova Scotia, Tantallon, 1991, 197p. (Coll.: Peoples of the Maritimes).

Pier 21 - Canada's Immigration Museum. Pier 21: The first Seventy-Five years. April 13, 2007 [Online]

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Carte de la Nouvelle-

Carte de la Nouvelle-

Écosse, 2006 -

Comtés de la Nouvelle

Comtés de la Nouvelle

-Écosse, 1881 -

Dartmouth et Halifax,

Dartmouth et Halifax,

Nouvelle-Écos... -

École normale, Truro

École normale, Truro

, N.-É., vers ...

-

Halifax, Nouvelle-Éc

Halifax, Nouvelle-Éc

osse -

Homme labourant avec

Homme labourant avec

deux boeufs (No... -

La ville et le port d

La ville et le port d

e Halifax, 1764 -

Nouvel établissement

Nouvel établissement

sur l'île du ...

-

Nouvelle-Écosse, 184

Nouvelle-Écosse, 184

0 -

Partie du Canada où

Partie du Canada où

se trouvent le ... -

Port d'Halifax, Nouve

Port d'Halifax, Nouve

lle-Écosse, 19... -

Régions acadiennes, 2

Régions acadiennes, 2

006

-

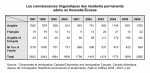

Tableau statistique d

Tableau statistique d

e la langue maî... -

Vue de la partie nord

Vue de la partie nord

de la ville d'... -

Yarmouth vue depuis M

Yarmouth vue depuis M

ilton (Nouvelle...