The image of Toronto in the work of Franco-Ontarian writers

par Sylvestre, Paul-François

Within a generation or two, the representation of Toronto in Franco-Ontarian literature was transformed, as the Ontario capital changed from a boring Anglo-Saxon city into a major multicultural one. In the contemporary novel in particular, the Queen City revealed an array of surprising and attractive aspects. It was in turn the city that Canadians love to hate, the rival of Montreal, the personification of government, the Canadian gay mecca, and the city with the longest street in the world.

Article disponible en français : Toronto dans l’imaginaire des écrivains franco-ontariens

The rise of a literary identity

According to Professor René Dionne (Note 1), a historian of Franco-Ontarian literature, Toronto's literary history consists of seven periods: French origins (1610-1760), Franco-Ontarian origins (1760-1865), the literature of civil servants (1865-1910), the affirmation of collective identity (1910-1927), defenders of language and culture (1928-1959), the literature of academics (1960-1972), and contemporary literature (since 1973). Although the Franco-Ontarian literary corpus goes back as far as the early seventeenth century, the literary works considered in this article come from a more limited period of time: except for two works published in 1855 and 1922 respectively, the main focus will be on novels published in the contemporary period.

Joseph-Charles Taché, a member of the Parliament of the Province of Canada (or United Canada) in Toronto, journalist, and senior civil servant in Ottawa, was one of the first writers to speak of Toronto. In 1855 he wrote: "Toronto is Upper Canada's largest city, and the third-largest in United Canada; it is favourably located on a bay serving as a port. This city is built like modern American cities, with very wide streets in a grid pattern. It is a large commercial centre." (Note 2) Taché's treatment of his subject is mainly from a an economic point of view.

Lionel Groulx, on the other hand, takes an ironic view of Toronto's Francophone face. His novel L'Appel de la race (1922) is entirely centred on the struggle of Franco-Ontarians against Regulation 17, which from 1912 to 1927 limited the use of French in Ontario schools. Groulx's work gives the impression that the author would have preferred not to have French taught in Toronto, rather than to propagate a language that Quebecois did not recognize as their own, and to reduce to a patois the heritage that they had been defending with devotion and tenacity for two centuries. Here is now the author describes the class in which the four Lantagnac children, from a mixed English-French family, are gathered around the father: "the teacher found himself faced with that 'beastly horrible French', which the Toronto gazettes mock so bitterly and attribute to the Quebec peasant. Wolfred and William spoke a little better perhaps, since they had associated with French-Canadian friends at Loyola College. Nellie and Virginia articulated, oh heavens! true Ontario-style French, the pure authentic 'Parisian French'". (Note 3)

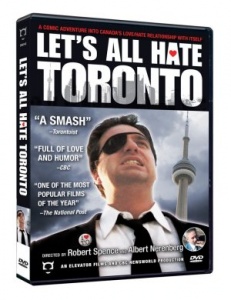

"Let's All Hate Toronto"

It is often said that of all the cities in the country, Toronto is the one that Canadians most love to hate. This sentiment goes back more than a half century: an album by Jack McLaren, titled Let's All Hate Toronto: narration, illustration, exhortation, appeared in 1956. People pontificated cheerfully about the city without even visiting it. Writers, who knew Toronto, didn't hesitate to portray it in ways similar to the idea some segments of the population held, rightly or wrongly, of the Queen City.

Gérard Bessette, who lived all his adult life in Ontario, was well aware that English-speaking Torontonians had changed over the years, and that they were not blinkered or hostile to the Francophones of his native Quebec. In his novel L'incubation, the narrator imagines a scene that could very well take place in the living room of the mother of one of his characters who lives in Toronto: "... there was a grand piano; on the walls were family portraits of Orange loyalists rep by pop Mazodelarochians and half-Orangists quarter-Orangists gradualist bonentendistes as time passed pancanadianists, a mari usque ad, changing with the times at just the right speed, reasonably bilinguist biculturalist..." (Note 4)

Hostility toward Toronto is sometimes expressed in terms of rivalry, especially with Montreal. The novelist Jean Éthier-Blais even recognizes Toronto's lead over Montreal in art, at least in the plot of his novel Les pays étrangers. Torontonians appear there in the 1940s as more advanced than Montrealers in matters of art collection: "The purchase of paintings, the establishment of an intelligent, rational collection, did not exist in Montreal society. This could be seen by comparing the donations made to the Toronto museum with those made to the Montreal museum by local collectors. Leftovers, it must be admitted.. Leftovers, and old masters of uncertain provenance." (Note 5)

The novel in which Toronto is most clearly compared with Montreal is Antonio d'Alfonso's Un vendredi du mois d'août. The thirteenth chapter is entirely devoted to a deliberately subjective analysis of the relative advantages of the two cities. Their names are never mentioned, except for the initial. D'Alfonso has his narrator say that Toronto is conservative but not puritanical, decadent but rich. Elegant, sophisticated, a great multicultural metropolis, Toronto is what the future of the country looks like, while Montreal is seen as rather provincial. Here is how T. and M. are compared in Antonio d'Alfonso's imagination: "M. bends over backwards to please minorities. T., loved especially by the cultural communities, is unabashedly contemptuous of anything foreign. It speaks more than ninety languages every day. But it rules in English. [...] M. warns you before looting you. T. takes everything, as it gives you its fine hypocritical smile." (Note 6)

Yonge et Queen Streets

City streets are outdoors, but they reflect the private life of the inhabitants. For writers, the street is a privileged place for representation, as well as an unceasing play of characters: beggar, little old lady, incompetent glazier, frivolous coquette. In Toronto, Yonge street is the stage on which the show is most striking. It is the main street, the thoroughfare separating the east of the city from the west. It's no surprise that it has caused a lot of ink to flow. Queen Street also plays its part in the imagination of writers.

It is often said that Yonge street is the longest street in the world, stretching out about 1,900 kilometres. The street begins at Lake Ontario and rises to the north, crosses the "strip" and enters the Rosedale neighbourhood, then runs beside Mount Pleasant cemetery, into Richmond Hill and Oak Ridges, and on to Aurora and Newmarket. This route is only 56 kilometres long. Where then does the 1,900 km come from? The answer is that Yonge Street is part of Ontario Highway 11, which runs to North Bay and then to Cochrane and Kapuskasing, and finally to Thunder Bay. Yonge street is a sort of condensed version of the city. In French, the word rue (street) suggests ru (a small stream), rut, and ruée (a rush or stampede), and Yonge street has all these aspects. New arrivals dream of living there; they come from all cultural horizons, in the hope of becoming, for one night, part of a film.

In Didier Leclair's novel Toronto, je t'aime, the character Raymond arrives from Benin and quickly finds Yonge Street, extending like a reptile whose length symbolizes eternal growth:

"On its sidewalks all kinds of human life were in constant movement, swarming and pulsating, like ants around their reproducing queen. How many productions my eyes saw on that day! What apparitions, what new races, colours, shop windows! From one intersection to another Yonge Street was alternately clean, miserable, grotesque. It was decaying in some places, sparkling in others." (Note 7)

Queen Street owes its name to Queen Victoria. In the past its western section was home to large Irish, Polish and Ukrainian communities. Today Queen Street is known for its shops, restaurants, hair salons and radio and television studios. Patrice Desbiens is probably the first Franco-Ontarian writer to have written a whole poem about Queen Street. It appeared in L'espace qui reste, an anthology published in 1979. The poet has just had his thirtieth birthday, and he describes the young people who drive up and down this street at the wheel of "leurs minounes rouillées" (their rusty cars), in the rhythms of the 1970s sub-cultural icons:

"it's friday night on / queen street east and / young people enter and leave / the restaurants. / coke. / gum. / undomesticated youth in their / tight jeans. / the rolling stones playing / in their eyes. / dylan on the radio. / tomcats in their / rusty cars. / fritz the cat from the / suburbs in / daddy's car. / ads for the / canadian armed forces / on the radio. / it's toronto in the friday night / of my bones." (Note 8)

A gay mecca

Toronto bears proudly its title of Canada's Gay Mecca. It is home to the largest LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community in Canada. It holds the biggest Gay Pride parade on the last Sunday in June, attracting close to a million spectators. The LGBT community is very visible in Toronto, with its own neighbourhood, its shops, its institutions and its press.

The heart of Gay Village is located at the intersection of Church and Wellesley Streets, where the action of Paul-François Sylvestre's 69, rue de la Luxure takes place. This neighbourhood is described by the narrator in the first lines of the novel:

"A middle-aged couple are walking in Toronto. They stroll along Church Street and stop at the corner of Wellesley Street, in the heart of a lively, colourful area. The woman has noticed the rainbow-coloured banners floating above each restaurant, shop and bar; she wonders aloud if this is a summer decoration or some special symbol. The man doesn't answer, because he doesn't know the meaning of the flag with its six brightly coloured stripes: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet. I am walking just behind this couple and I am tempted to tell them the answer: this is the flag that identifies the homosexual community in many countries, including Canada." (Note 9)

Toronto as the personification of government

The name of a capital city is often used to refer to the government itself. Instead of "the government of Ontario," the shorter term "Toronto" is used. In a study published on the occasion of the centennial of the present Ontario Legislative Building (Note 10), Roger Hall mentions "a conflict between Toronto and Ottawa" to refer to the dispute between the Premier of Ontario, Mitchell Hepburn, and the Prime Minister of Canada, William Lyon Mackenzie King. The use of a city to represent a government appears also in novels. Daniel Poliquin, the author of Temps pascal, refers in three consecutive paragraphs to Toronto in the sense of provincial government, using very common expressions: "to refer it to Toronto," "to force Toronto's hand," "to defy Toronto."

The protagonist of Temps pascal is Médéric Dutrisac, a teacher who persists in teaching in French during the time of Regulation 17. Poliquin writes: "Within a few weeks, the whole Nipissing school district knew about the matter. [Inspector] Danis himself spread the story, secretly hoping that people would imitate young Dutrisac to force Toronto's hand some day. With time, it would come. That is precisely what happened." (Note 11) And that is what really did happen.

A lively literary culture

Franco-Ontarian writers have set characters in Toronto, described streets and neighbourhoods of the Queen City in their narrations, and have even sought poetic inspiration from Toronto. Their works echo the Francophone vitality of Ontario, and in doing so, take their place in the cultural heritage of French America.

Paul-François Sylvestre

Writer and literary critic for the Toronto Express

Additional DocumentsSome documents require an additional plugin to be consulted

Images

-

Angle des rues Yonge

Angle des rues Yonge

et Wellesley, 2... -

Antonio D'Alfonso, ph

Antonio D'Alfonso, ph

otographie offi... -

Comment franchir la r

Comment franchir la r

ue Yonge -

Couverture du livre «

Couverture du livre «

69, rue de la L...

-

Cover of the book Tor

Cover of the book Tor

onto je t'aime,... -

Daniel Poliquin

Daniel Poliquin

-

Didier Leclair

Didier Leclair

-

Foule rassemble à l'o

Foule rassemble à l'o

ccasion du défi...

-

Gérard Bessette

Gérard Bessette

-

Jacket of the film "L

Jacket of the film "L

et's all hate T... -

Joseph-Charles Taché

Joseph-Charles Taché

-

L'Appel de la race, b

L'Appel de la race, b

y Lionel Groulx

-

Panorama de Toronto

Panorama de Toronto

-

Pride Parade, Toronto

Pride Parade, Toronto

, 2008 -

Queen Street, Toronto

Queen Street, Toronto

, 2008 -

Rue Yonge, Toronto, O

Rue Yonge, Toronto, O

nt., vers 1907

-

Samedi soir sur la ru

Samedi soir sur la ru

e Yonge, 2006 -

Street sign at Yonge

Street sign at Yonge

Street, in down... -

Toronto seen from the

Toronto seen from the

CN Tower, just... -

Vue nocturne de Toron

Vue nocturne de Toron

to, 2007

Catégories

Notes

1. René Dionne, Histoire de la littérature franco-ontarienne des origines à nos jours, tome 1, Sudbury, Prise de parole, 1997, p. 15-16.

2. Joseph-Charles Taché, Esquisse sur le Canada considéré sous le point de vue économiste (sic), Paris, Hector Bossange et Fils, 1855 (cité dans René Dionne, Anthologie de la littérature franco-ontariennes des origines à nos jours, tome II, Vermillon, 2000, p. 73).

3. Lionel Groulx, L'Appel de la race, Montréal, Éditions Fides, 1956, p. 120-121.

4. Gérard Bessette, L'Incubation ,Montréal, Éditions Déom, 1965, p. 164.

5. Jean Éthier-Blais, Les Pays étrangers, Montréal, Leméac, 1982, p. 70.

6. Antonio D'Alfonso, Un vendredi du mois d'août, Montréal, Leméac éditeur, 2004, p. 54-55.

7. Didier Leclair, Toronto, je t'aime, roman, Ottawa, Éditions du Vermillon, 2000, p. 36.

8. Patrice Desbiens, l'espace qui reste, Sudbury, Prise de parole, 1979, p. 49.

9. Paul-François Sylvestre, 69, rue de la Luxure, Toronto, Éditions du Gref, 2004, p. 7-8.

10. Roger Hall, Un Centenaire à fêter (1893-1993) : l'Édifice de l'Assemblée législative de l'Ontario, Toronto, Assemblée législative de l'Ontario et Dundurn Press, 1993, p. 135.

11. Daniel Poliquin, Temps pascal, Ottawa, Éditions Le Nordir, 2003, p. 125.

Bibliographie

Bessette, Gérard,L'Incubation, roman, Montréal, Éditions Déom, 1965, 178 p.

D'Alfonso, Antonio, Un vendredi du mois d'août, roman, Montréal,Leméac éditeur, 2004, 144 p.

Desbiens, Patrice, l'espace qui reste, poésie, Sudbury, Prise deparole, 1979, 92 p.

Dionne, René, Histoire de lalittérature franco-ontarienne des origines à nos jours, tome 1, Sudbury,Prise de parole, 1997, 364 p.

Éthier-Blais, Jean. Les Pays étrangers, roman, Montréal, Leméacéditeur, 1982, 468 p.

Groulx, Lionel. L'Appel de la race, roman, Montréal, ÉditionsFides, 1956, 252 p.

Hall, Roger, Un Centenaire àfêter (1893-1993) : l'Édifice de l'Assemblée législative de l'Ontario,Toronto, Assemblée législative de l'Ontario et Dundurn Press, édition bilingue,1993, 164 p.

Leclair, Didier, Toronto, je t'aime, roman, Ottawa, Éditions duVermillon, 2000, 182 p.

Poliquin, Daniel, Temps pascal, roman, Ottawa, Éditions LeNordir, 2003, 164 p.

Sylvestre, Paul-François, Torontos'écrit : la Ville Reine dans notre littérature, essai littéraire,Toronto, Éditions du Gref, 2007, 216 p.

Sylvestre, Paul-François, 69, rue de la Luxure, roman, Toronto,Éditions du Gref, 2004, 200 p.

Taché, Joseph-Charles, Esquisse sur le Canada considéré sous lepoint de vue économiste (sic), Paris, Hector Bossange et Fils, 1855 (citédans René Dionne, Anthologie de la littérature franco-ontariennes desorigines à nos jours, tome II, Ottawa, Éditions du Vermillon, 2000, 384 p.)